A grad student’s DIY $27 air filter could help Chinese city-dwellers breathe easier

The air in Chinese cities has been so polluted as to be unsafe for nearly half the days so far this year. The dismal air quality makes air purifiers a necessity, especially for families with young children, but they are painfully expensive—so Thomas Talhelm decided to MacGyver his own.

The air in Chinese cities has been so polluted as to be unsafe for nearly half the days so far this year. The dismal air quality makes air purifiers a necessity, especially for families with young children, but they are painfully expensive—so Thomas Talhelm decided to MacGyver his own.

During the airpocalypse in January, when pollution levels in Beijing were a record 30 to 45 times above recommended safety levels, “I was worrying about what that was doing to my health,” said Talhelm, a PhD psychology student from the University of Virginia living in Beijing on a Fulbright scholarship. “But then I thought, do I really want to spend thousands of dollars?”

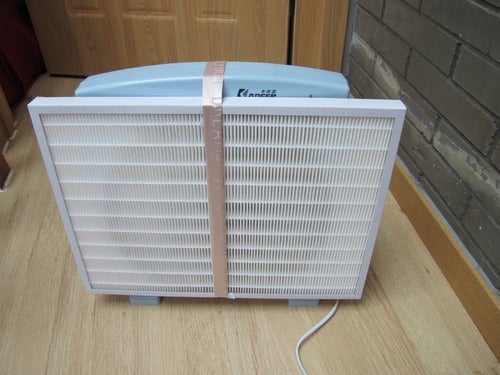

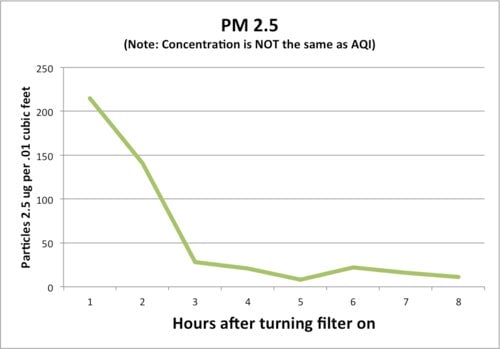

His solution couldn’t have been much more basic: A high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter strapped to a box fan, total cost $27. “It’s pretty ghetto,” he said wryly, but it worked. Using a handheld air quality monitor, he found that his filter drastically reduced his apartment’s level of PM2.5 particles—the kind that are the most harmful to human health, 2.5 microns and smaller.

Although it’s not an exact comparison, Talhelm’s filter showed similar results to the tests that Dr. Richard Saint Cyr, a Beijing physician, conducted on two popular brands of air filter sold in China: the IQAir 250 ($2,446) and the Blueair 501 ($980). (Here’s another set of tests on a broader range of filters by the Shanghai Consumer Rights Protection Commission.)

Air filters and other products that help people cope with pollution have become big business in China. IQAir sold out of devices during the airpocalypse, and sales of Japanese brands surged. But much of the action has been at the high end of the market, where filters often cost an average city-dweller’s monthly salary and companies can put up an artificial dome over a private school playground for half a million dollars.

If a non-engineer like Talhelm could put together a cheap and effective air filter for a fraction of the going cost, why aren’t there thousands of Chinese firms competing to bring more affordable devices to a massive, desperate pool of consumers? The answer may be in the way that air filters work: invisibly, with hard-to-measure results. Especially in China, where trust in businesses is low, people put their trust in the most expensive filters.

The biggest change, he said, is that people finally realize that urban pollution has become so bad that it is a serious danger to their families’ health. The Chinese government has finally admitted that pollution is a problem, and the subject is no longer taboo.

“When I first came to Beijing in 2006 there’d be disgusting air and people would say ‘it’s really foggy today.’ Now it’s not like that. During the airpocalypse people started talking about pollution, not fog,” he said. “I don’t know if the air’s gotten much worse since then, but now people know about it and they want to do something about it.”