Maine’s lobster bubble is threatening to burst, thanks to global warming and Canada

Alarmingly low prices are pushing the US state of Maine’s famed lobster industry to the brink of collapse. The cause? The menacing double-whammy of climate change and…Canadians.

Alarmingly low prices are pushing the US state of Maine’s famed lobster industry to the brink of collapse. The cause? The menacing double-whammy of climate change and…Canadians.

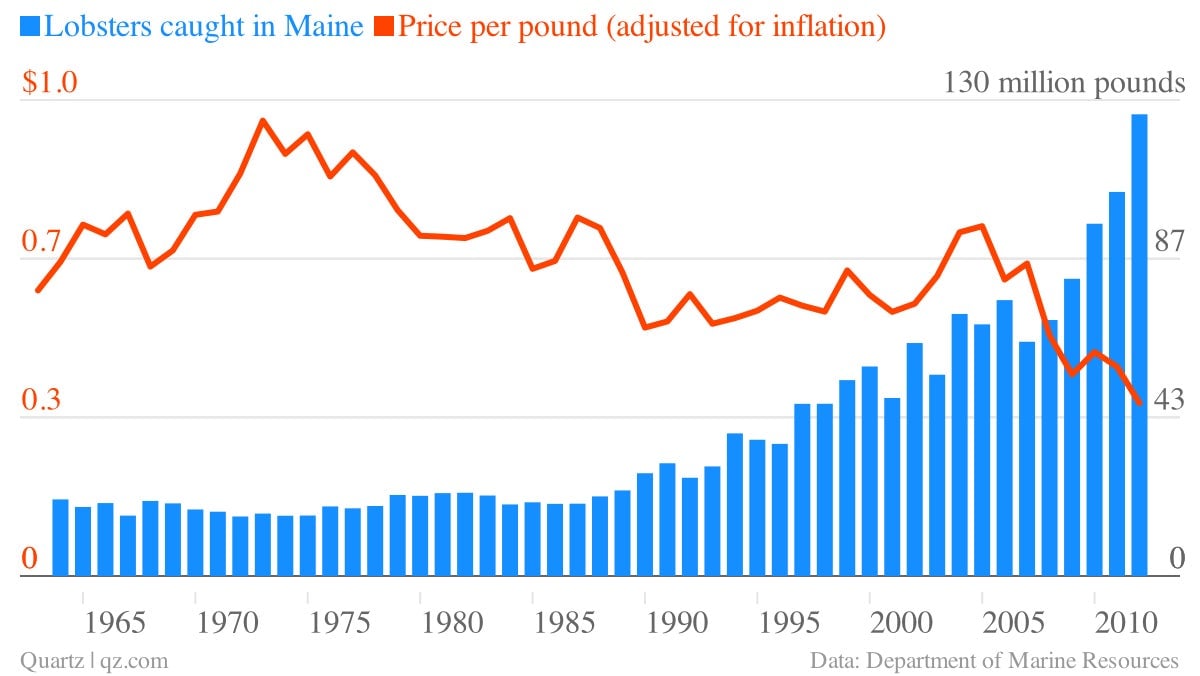

The first might sound familiar. Last year, shockingly warm seas caused an explosion of the lobster population of inland Maine waters. Lobstermen pulled in an off-the-charts 126 million pounds (57 million kg) of lobsters, driving down prices. Here’s a look at the trend:

Lobster “cheaper than deli meats” was a godsend for gourmands. But it was catastrophic for Maine’s lobstermen. By July 2012, prices had fallen as low as $1.25 per pound (paywall)—well below the break-even point of $4 per pound.

Fortunately for Maine, 2013 hasn’t been a scorcher. So why are prices still down?

Canada, it turns out. The country processes 60%-70%—though some say as much as 80%—of Maine lobsters. Only 10% are processed in Maine. That makes it hard to command high prices, especially now that the catches are booming in size. Much more of Maine’s lobster haul now heads north to Canadian processors, and a bumper crop of Canadian lobsters earlier this spring sopped up potential demand for those from Maine. That’s why Maine’s governor, Paul LePage, wants to open new processing factories in his state.

It’s not just pricing power, though. Canadians also best Mainers in marketing. At issue are hard- and soft-shelled lobsters. In the summer, lobsters shed their shells in order to grow in size. Those are the ones Mainers catch. But new shells toughen up when the water turns colder, such that by winter and spring, when Canadians tend to catch them, most have hard shells. While around 70%-80% of the catches Maine lobstermen haul up are soft-shelled, only around one-quarter of Canadian catches are.

“The Canadians who harvest hard-shells market them as superior,” said John Suave, a Lobster Advisory Council consultant, at a lobstermen meeting in Portland, Maine last year. The Mainers, naturally, argue that though the hard-shell lobsters have more meat, Maine’s soft-shell lobsters win on flavor. “Independent panels” have found that Maine lobsters are “sweeter and brinier,” John Stamell, CEO of FutureShift—a consultancy the Maine Lobster Promotion Council hired—tells Quartz. They’re also easier to crack open, says Stamell, which can make them easier for chefs to handle.

Those differences haven’t mattered much historically. Canada and Maine seldom competed—summer tourists scarfed down Maine’s lobsters, while Canadian catches were processed for export.

But marketing matters more now that lobstermen on both sides of the border are catching way more lobsters than ever before. Now Maine lobstermen are finding their catches dismissed for not having enough “bang for your buck,” as well as having their prices driven down—or their shipments blocked—when they sell to Canadian processing plants. The weaker brand is exacerbated by the fact that soft-shell lobsters don’t travel as well as hard-shell ones, so their market is more limited.

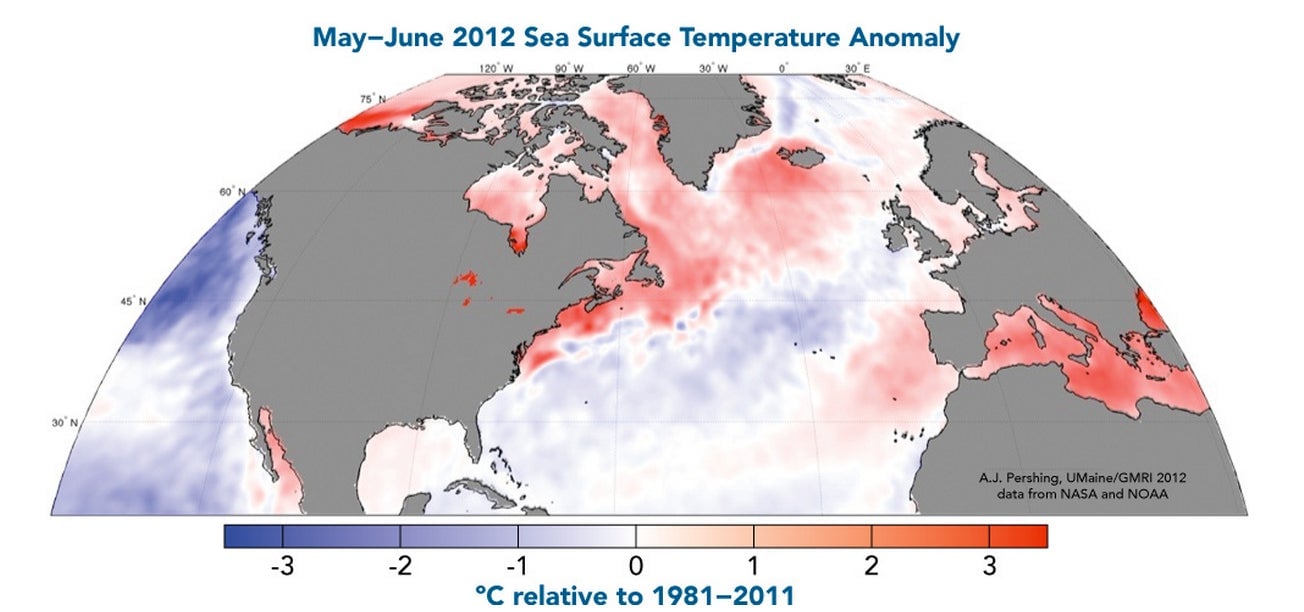

But Maine lobstermen may have more pressing concerns:

Despite this year’s reprieve, those temperatures are only rising. That trend has driven Atlantic lobsters north at a pace of around 10 miles a decade over the last 40 years, says Malin Pinksy, a Rutgers University ecologist. Plus, shell disease, which spreads more easily in warmer waters, has killed off nearly all of the lobsters that once swarmed the Long Island Sound and waters south of Cape Cod. And that means in the long run, the more devastating blow to Maine’s economy will be climate change, not Canadians.