Despite India’s economic woes, it’s a bright spot for BRIC-loving institutional investors

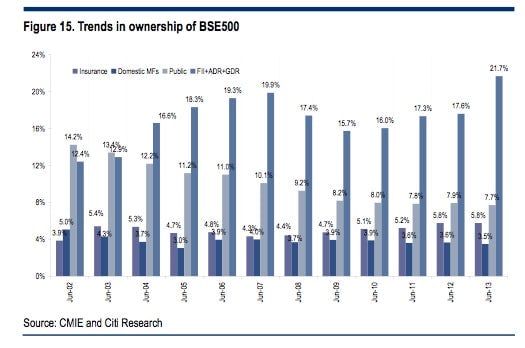

Foreign companies are fleeing India, the rupee continues to plumb new lows and the economy is so moribund that officials have named one of their sharpest critics as the new central bank chief. But foreign institutional investors, in the form of mutual and hedge funds, have amassed record-setting amounts of India’s top stocks this year. In June, they owned 21.7% of the Bombay Stock Exchange’s top 500 stocks and over $220 billion in Indian stocks overall, analysts from Citigroup noted this week.

Foreign companies are fleeing India, the rupee continues to plumb new lows and the economy is so moribund that officials have named one of their sharpest critics as the new central bank chief. But foreign institutional investors, in the form of mutual and hedge funds, have amassed record-setting amounts of India’s top stocks this year. In June, they owned 21.7% of the Bombay Stock Exchange’s top 500 stocks and over $220 billion in Indian stocks overall, analysts from Citigroup noted this week.

It’s a puzzling contradiction, but while investment conditions in India may seem bad, other emerging markets that many of these funds look at have been even worse. China’s Shanghai Composite Index has fallen further than any other in the world except Greece from its 2009 highs, as lending evaporated and businesses shut; foreign institutional investors yanked money from Russia after government critic Aleksey Navalny was sent to prison, and they fled Brazil after GDP stalled and protestors took to the streets.

India, with growth above 5% and a relative lack of political or social upheaval, looks pretty good by comparison. “A BRIC investor would have a more negative bias on Brazil, Russia and China than India,” said Rajeev Malik, senior economist, CLSA Singapore. “India appeared to be less worse-off.”

The country’s relative good fortune also presents a potential danger if sentiment changes and foreign investors leave en masse, as they are prone to do. There aren’t nearly enough domestic investors to pick up the slack, so the massive foreign institutional ownership of India’s stock markets “could be onerous,” Citigroup analysts warned, in part because it is so narrow. Over 86% of foriegn institutional investment is in India’s top 100 stocks, and 61% is in the top 30 stocks.

Investors haven’t exactly ignored India’s recent woes; foreign hedge funds and mutual funds dumped some $3 billion in Indian equity in June and July, and the Bombay Stock Exchange’s SENSEX Index is down 8 percent since late July. The SENSEX is generally volatile, though, and still more than double the five-year low it hit during the 2008 financial crisis.

Some are predicting steeper sell offs soon, as fears over China’s slowdown ease. “Once we get better data out of China and that will happen in September and October with growth moving back to 7.5 percent, then foreign capital will move back into the Chinese market,” Robert Parker, a Credit Suisse adviser, warned this month.

The bottom line for India: If it “doesn’t get its act together” and other developing markets resume their rapid growth, Malik said, then “all bets are off.”