Think China is “rebalancing”? Its real estate sector begs to differ

The last two days of China’s economic data announcements have markets rejoicing. Evidently, surprisingly passable industrial production and trade data are broadcasting more of a soft landing than a hard bang. The buzzword of the moment to describe China’s economy is “stabilizing,” and some have even gone so far as to use the “r-word.”

The last two days of China’s economic data announcements have markets rejoicing. Evidently, surprisingly passable industrial production and trade data are broadcasting more of a soft landing than a hard bang. The buzzword of the moment to describe China’s economy is “stabilizing,” and some have even gone so far as to use the “r-word.”

“Rebalancing,” that is. A watchword for China’s economic health for nearly a half-decade, the term refers to remedying China’s lopsided economy, which relies too much on investment and not enough on consumption; If the country is to continue to expand while avoiding a debt crisis, it must rebalance so that its consumers drive its growth.

By the looks of recent data, though, China seems to be championing a different r-word: relapse. And, as it happens, China’s relapse is related to a few other r-words: residential real estate.

Historically, the limited investment options created by China’s closed financial system have meant that real estate is pretty much the only thing households can invest in with reliable returns. That’s why China’s wealthy have snapped up apartments speculatively, often leaving them empty.

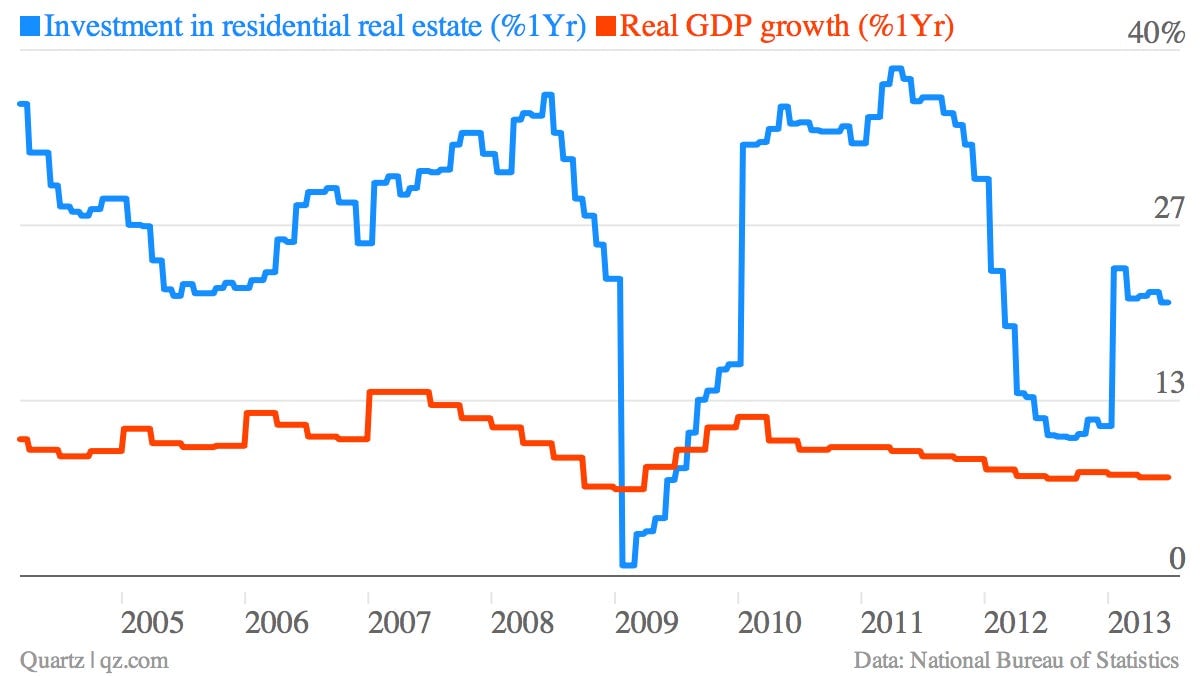

Chinese developers have fed this demand, investing 3.0 trillion yuan ($489 billion) in the first seven months of 2013, up 20.2% compared with the same period in 2012. That might explain the rosy industrial production data out on Aug. 9, according to a note by Société Générale’s Wei Yao today. ”The details suggest that reviving property construction drove most of the gain,” he writes.

This pace of property construction is dangerous—and not just because much of that is funded by shadow lending, which surged to 107.4 billion yuan in July. The growth rate in housing investment has far surpassed GDP growth, says Nicholas Borst of the Peterson Institute for International Economics. ”Given persistent reports of excess housing stock, it seems unlikely that this level of spending is justified by actual demand,” he wrote in a recent blog post.

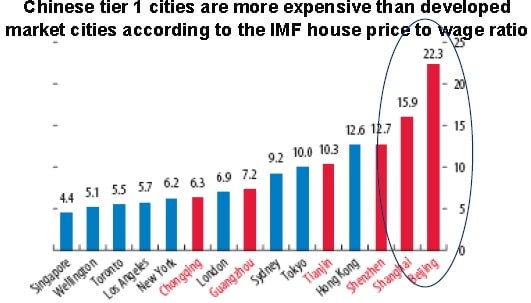

In theory, more investment in housing might be considered a good thing, since increased supply could ease housing prices, which, particularly relative to wages, are sky-high:

In practice, however, developers are building what they can earn the highest return on: fancy luxury condos designed for speculation, rather than properties most Chinese households can afford. Meanwhile, the government’s affordable housing plan isn’t helping much.

Local governments have preferred to build in smaller cities where demand is scanty, rather than allocate valuable land (pdf, p.12) in big cities to low-income housing. If at all—they’ve also siphoned off 5.8 billion yuan in funds they’ve received for affordable housing, reports Caixin.

This is hardly the way to encourage consumer spending. In fact, it has the opposite effect, says Jeff Walters, of Boston Consulting Group’s China office. ”Prices relative to incomes are quite high in China, and are driving [households] to save more,” he tells Quartz. ”If housing prices continue to rise, they might even bump up their savings rate.”

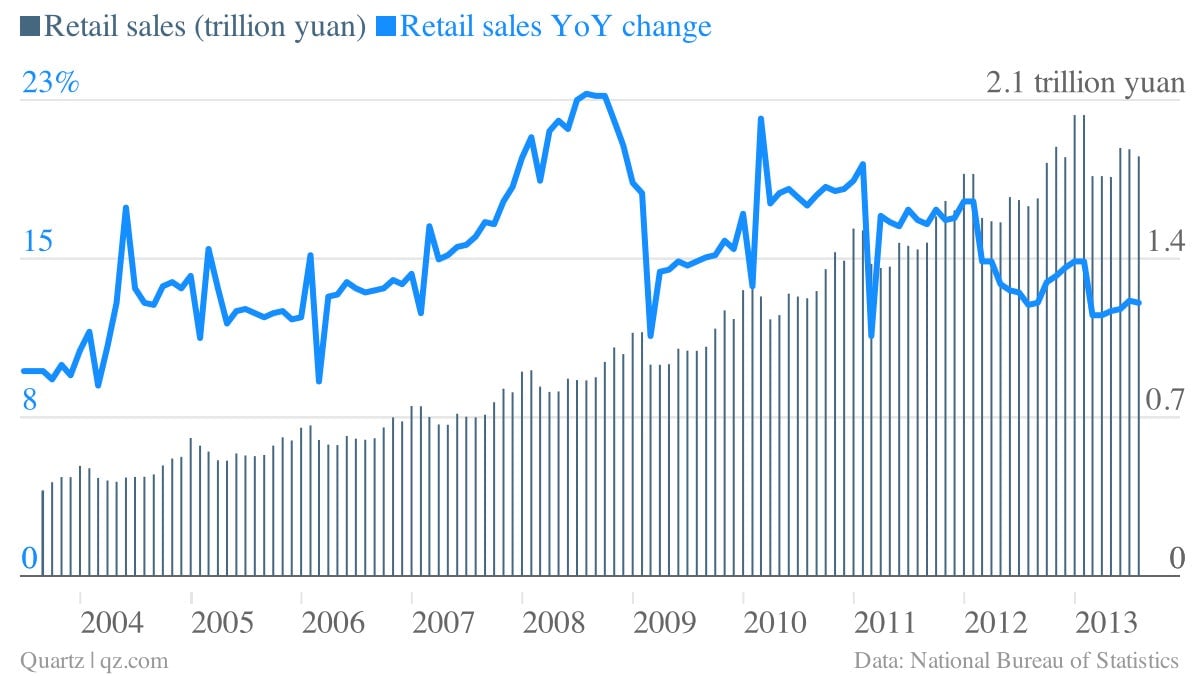

And, sure enough, retail sales are slowing:

The upshot of all this is that China probably does have ample housing supply. But it’s the wrong kind, in the wrong place. Until that changes, households will have to keep socking away even more of their wages. That makes the idea of “rebalancing” a thing of the future—or perhaps a thing of the past.