Why is a tax-cut loving accountant the first Republican senator to oppose his party’s tax plan?

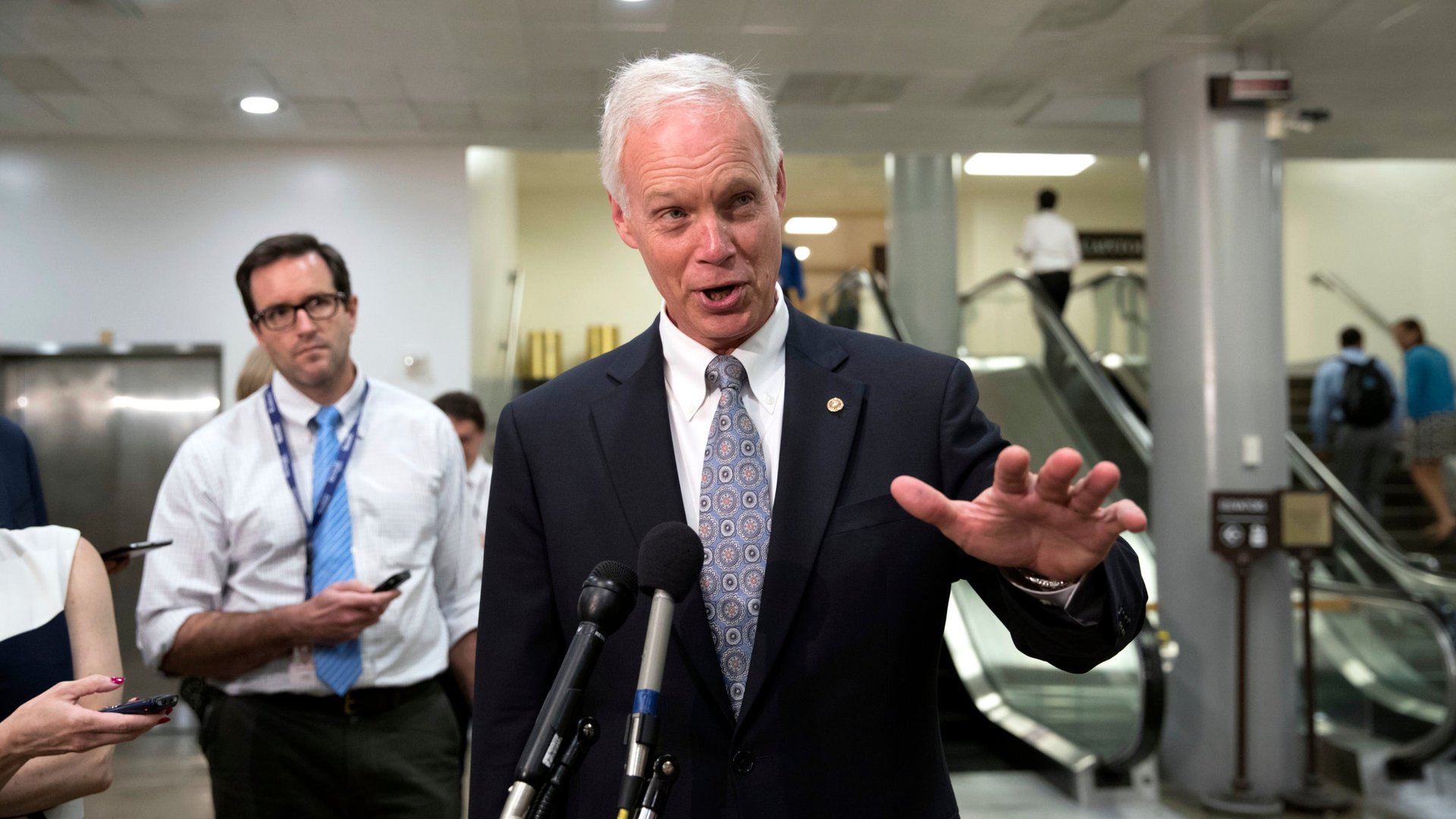

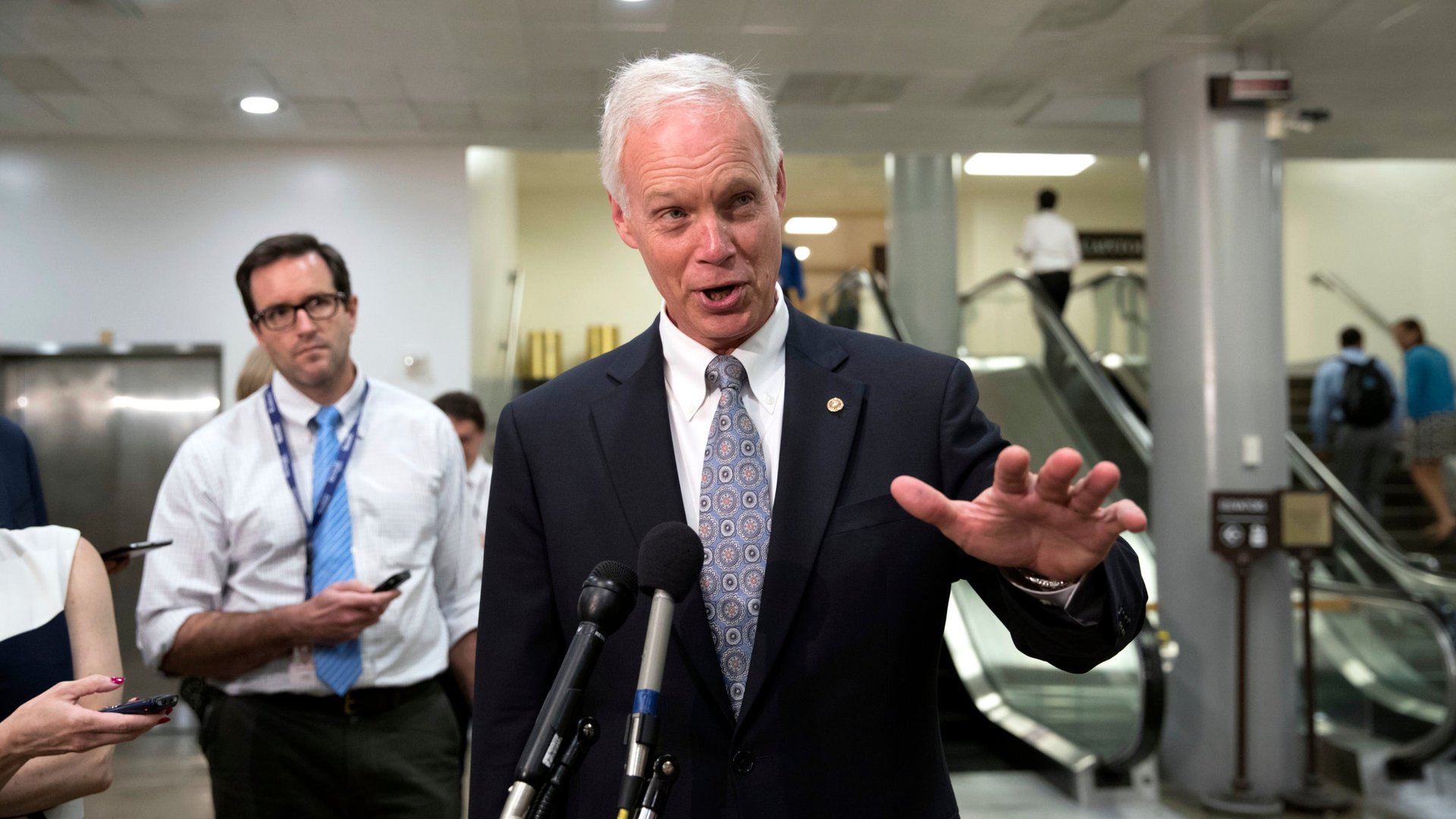

Senator Ron Johnson is a conservative Republican from Wisconsin, a trained accountant, and the founder of a family-owned manufacturing business. Unexpectedly, he is also the first Republican lawmaker to say he won’t vote for the senate’s tax bill as currently written.

Senator Ron Johnson is a conservative Republican from Wisconsin, a trained accountant, and the founder of a family-owned manufacturing business. Unexpectedly, he is also the first Republican lawmaker to say he won’t vote for the senate’s tax bill as currently written.

His complaint is that small businesses in the US don’t get enough of a break, while big multinational companies would reap enormous benefits. In other words, it might be described as an “America Last” tax bill.

At issue is how people who operate businesses as “pass-through entities”—that is, they pass their business income on to their individual income tax return—should be taxed.

Most American businesses are pass-throughs, and about half of American workers are employed by them. The owners of these businesses range from small contractors and shop-keepers to white-collar professionals like doctors and lawyers, as well as owners of investment trusts or celebrities who are paid to endorse products. This range of interests makes it tricky to apply a fair approach to all.

In the senate bill, pass-through entities are allowed to deduct just over 17% of their business income, an effort to reduce the rate paid on business income to come closer to the 20% rate the bill sets for corporate income (down from 35% today). This will still leave many pass-throughs paying a far higher rate than corporations, however, and that’s Johnson’s problem: Why should Wal-Mart pay a lower tax rate than your local hardware store?

The problem becomes magnified by the ways that senate Republicans make up for some of the costs of their plan. First, the tax cuts for individuals and pass-throughs alike expire in 2022, while the corporate tax cuts are permanent. Second, they eliminate the current deduction for state and local taxes for individuals. This would affect pass-through entities as well, while corporations can still deduct local levies as an operating expense.

Johnson argues that every business should become a pass-through entity, which would guarantee a level playing field, while also effectively eliminating business taxes. This would cost the US government lots of revenue, so it’s very unlikely to end up in the current bill. It’s not yet clear what would bring him on board, but it would likely be a bigger deduction for small businesses to bring them closer to the corporate rate. “There’s no way I want to block this,” he told the New York Times.

The National Federation of Independent Businesses, a powerful lobby for pass-through entities, has endorsed the existing proposal, because it does represent a significant tax cut for their members. But Johnson’s opposition is a reminder that this bill’s biggest tax cut benefits a very specific sector of the economy: Shareholders in large multinational companies that earn significant amounts of money outside of the United States.