The emotional benefits of small talk outweigh your fear of being awkward

At an early age, you’re taught not to talk to strangers. Originally meant to protect us from childhood harm, this rule follows most of us into adulthood.

At an early age, you’re taught not to talk to strangers. Originally meant to protect us from childhood harm, this rule follows most of us into adulthood.

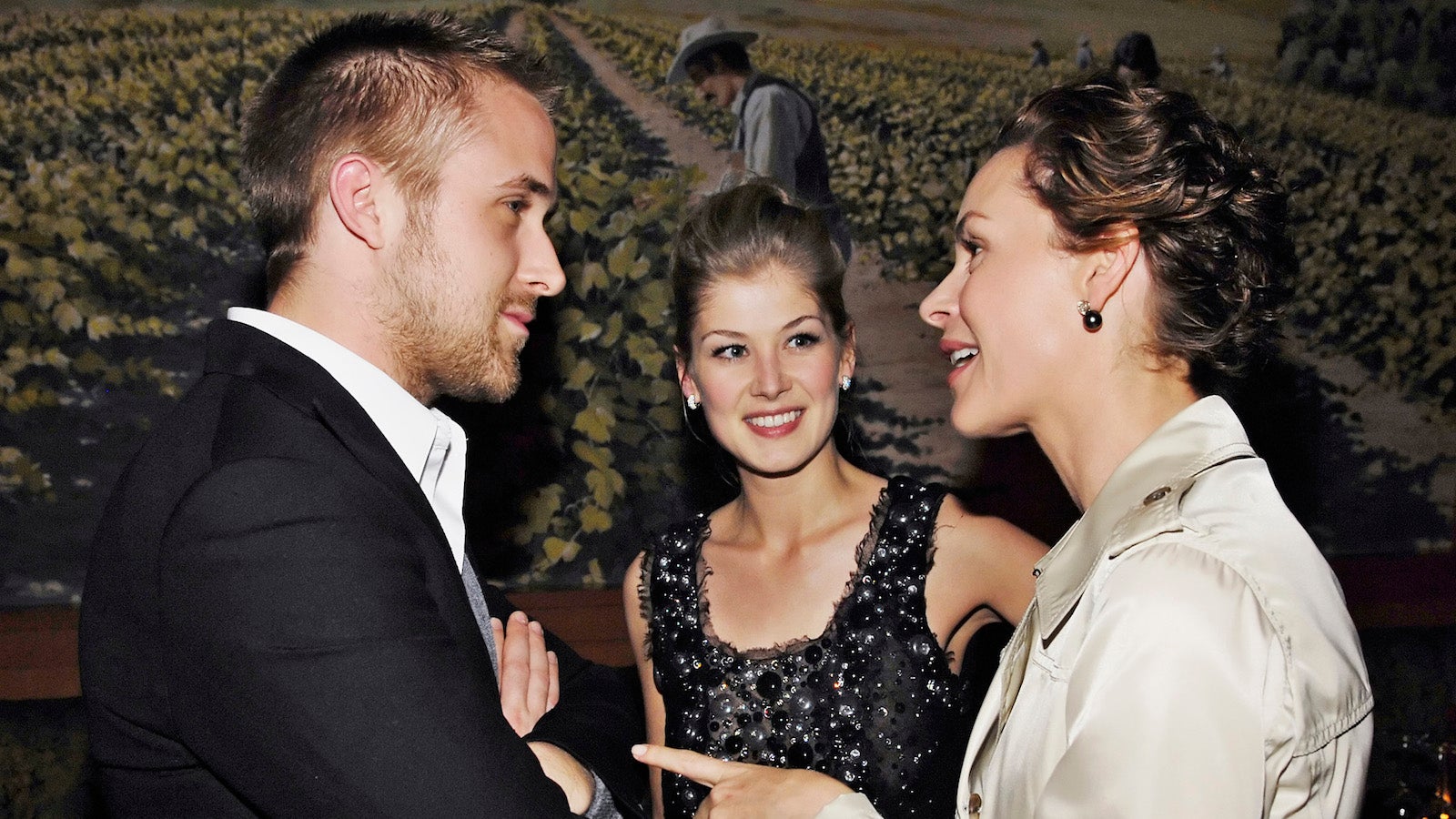

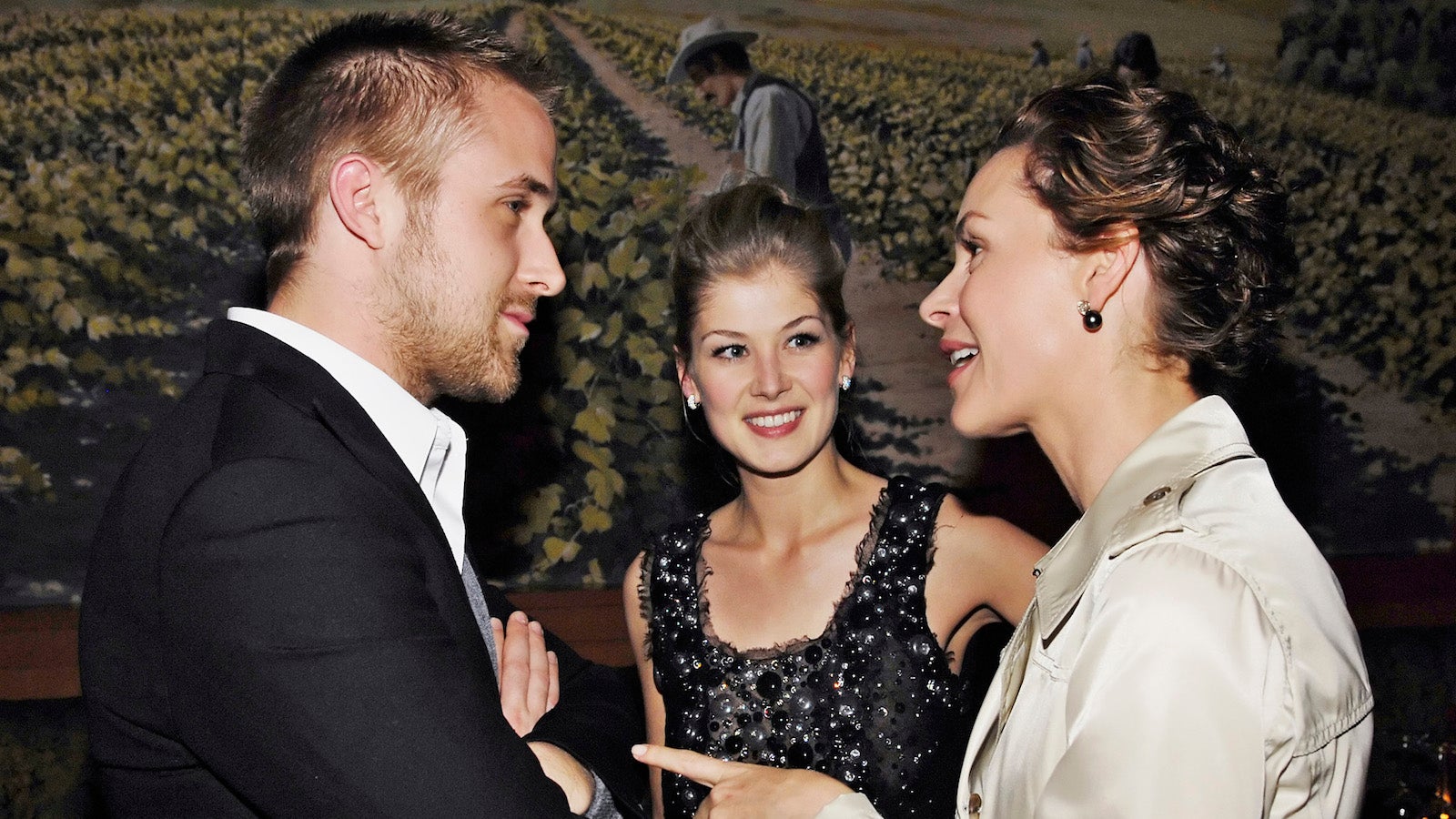

We keep to ourselves in public places. We avert our eyes on public transport. We stand frozen in the corners of cocktail parties and extended family gatherings, preferring to chat to the few folk we know rather than risk a conversation with an unknown entity. When you’re greeted with a rogue “Good morning!” as you pass the neighborhood fruit seller, you might jump, wondering what they want, or if you’ve spilled coffee down your front.

These chats are usually quick—a comment about the weather, a long line, a delayed bus. Others turn into much longer conversations about houses and hometowns, current and previous jobs, and family and friends. And is that moment of spontaneous human connection really such a horrible thing?

When we think of small talk, we see it as awkward and painful. There’s a fear of rejection that comes with attempting to start a conversation, or a feeling of having nothing in common with a stranger. We may have no interest in talking to people we don’t know or assume they aren’t interested in what we have to say.

“We call this pluralistic ignorance,” says Juliana Schroeder, a psychologist and assistant professor at University of California, Berkeley. “People mistakenly infer others’ attitudes from their behavior when their behavior is actually dictated by norms. In this case, people see everyone not talking and assume they don’t want to talk, but actually everyone is more interested in talking than they believe.”

These barriers hold us back from connecting with strangers, so we choose solitude instead. But we may have chosen wrong.

In a study conducted by Schroeder and Nicholas Epley, a behavioral-science professor at the University of Chicago, they found that interacting with strangers results in a more positive experience than solitude. The study involved commuters on trains and public buses, people riding a cab to the airport, and people sitting in a simulated waiting room. Those who were instructed to strike up a conversation with someone new on public transport or with their cab driver reported a more positive commute experience than those instructed to sit in silence. The researchers also wanted to verify whether the positive effects of social connection extend to those who were spoken to by creating a situation resembling a waiting room. Results showed that the experience was positive for both the conversation starter and the person approached for conversation in the simulated waiting room.

Another group of commuters were asked to simply imagine their experiences. Those who were instructed to strike up a hypothetical conversation with a stranger said they expected a negative experience as opposed to just sitting alone. But Schroeder and Epley’s experiment predicted otherwise. “People systematically misunderstand the consequences of social connection,” they said, “mistakenly thinking that isolation is more pleasant than connecting with a stranger, when the benefits of social connection actually extend to distant strangers as well.”

These distant strangers can be what another study calls “weak ties”: acquaintances such as a barista at your local coffee shop, a work colleague, a yoga classmate, or someone who walks their dog on your route home. According to the study, weak-tie relationships entail “less frequent contact, low emotional intensity, and limited intimacy.” Regular interactions with weak ties contribute to a better social and emotional well-being.

“We found that genuine social interactions—even minimal ones—contribute to fulfilling our basic human need to belong,” says Gillian Sandstrom, a psychology lecturer at the University of Essex and the primary author of the study on weak ties. “By chatting with a stranger, you are being seen and acknowledged, and your connection to that one person may remind you of your universal connection to other people.”

But there’s more to small talk than just social connection and improved well-being. A study published in the Social Psychological and Personality Science Journal found that brief getting-to-know-you interactions boost the brain’s executive functions, which are the mental processes that allow us to focus, plan, prioritize, and organize.

Researchers instructed a group of participants to engage in a 10-minute friendly conversation before going through cognitive tests that involved the brain’s executive functions, such as a speed test of matching patterns or connecting letters or numbers in order. A second group was asked to engage in competition-based conversation while a third group had no prior interaction at all. The group that engaged in friendly small talk performed better in the tests, with researchers highlighting improvements specific to the brain’s executive functions.

There are opportunities around us to engage in small talk every day. Schroeder’s advice is to make these conversations more of a habit, especially in places like public transportation or waiting rooms. Meanwhile, Sandstrom suggests smiling and making eye contact as a way to start up a conversation with strangers. “Try to genuinely connect with them. Be observant and tap into your curiosity,” she adds.

So on your commute tomorrow, your break at the office coffee machine, or at a holiday party, try to engage someone in a bit of small talk. You never know where the conversation might lead.