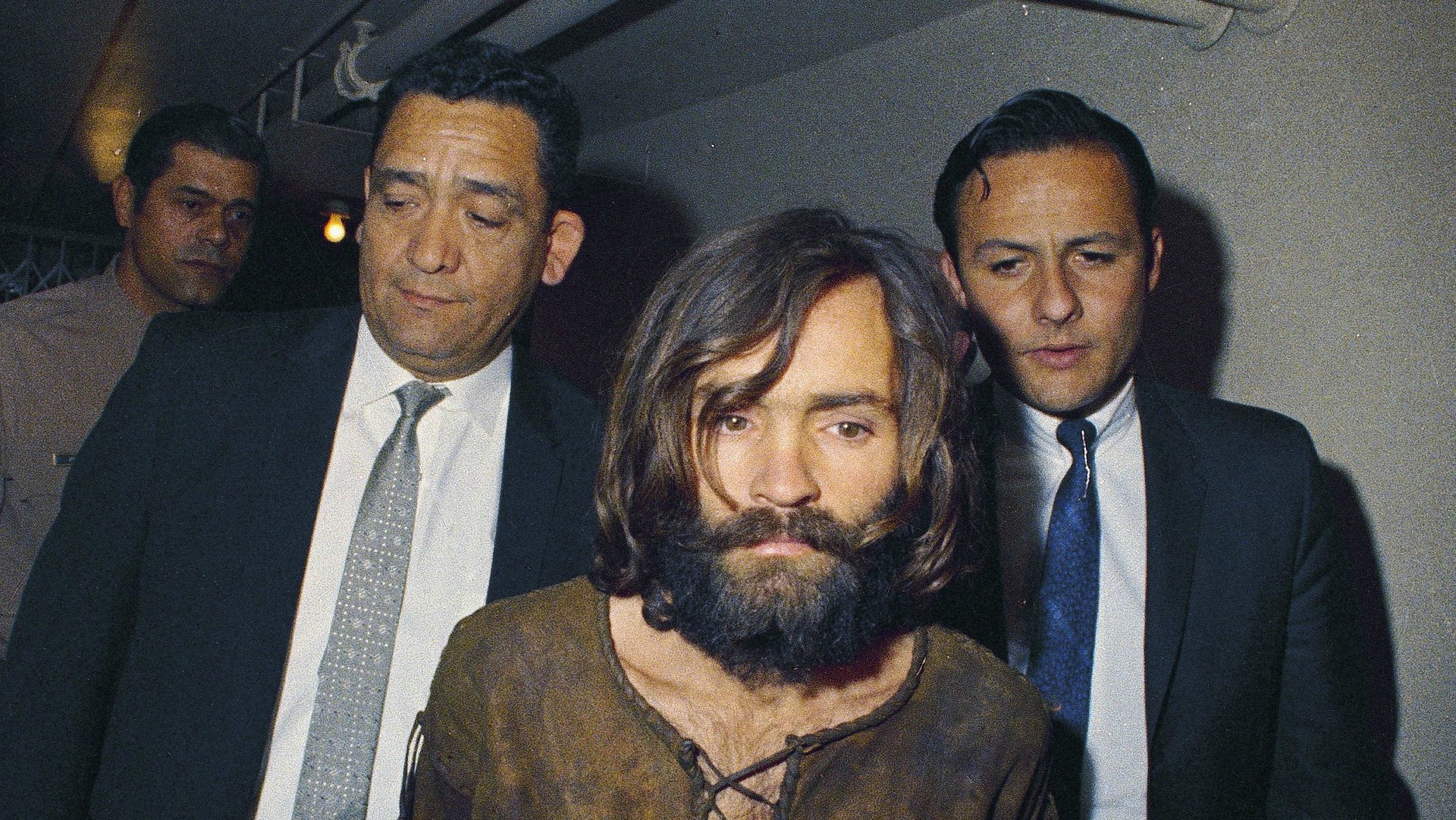

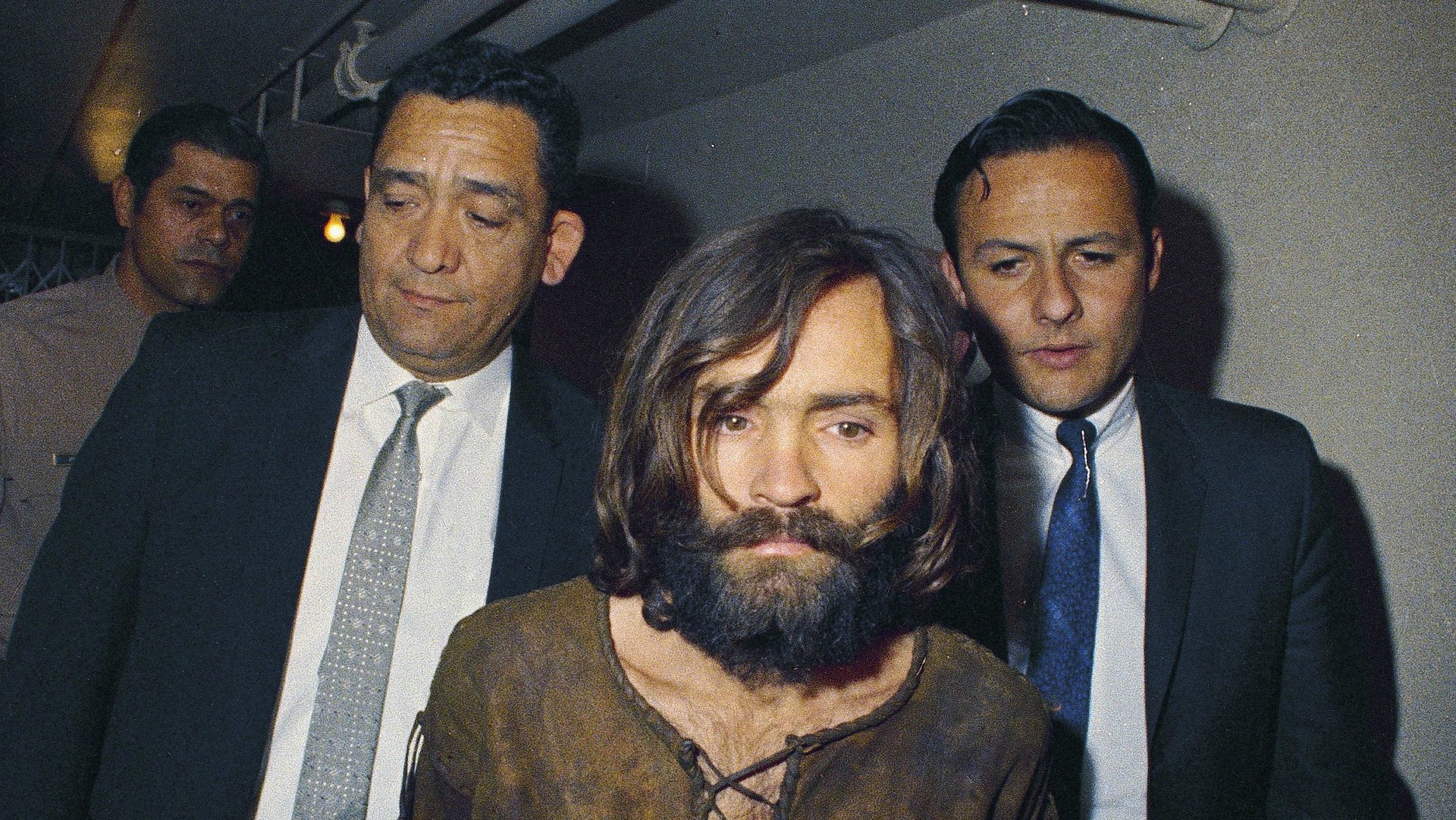

All the ways we’ve tried to fit Charles Manson into a convenient narrative

Satan. Sociopath. Psychopath. Narcissist. Eco-warrior. Opportunist. Manipulator. White supremacist. Misogynist. Executioner of hippie culture. Embodiment of evil. These are just some of the ways Charles Manson, the notorious 1960s killer and cult leader, has been described in the countless obituaries published since his death at 83 on Nov. 19.

Satan. Sociopath. Psychopath. Narcissist. Eco-warrior. Opportunist. Manipulator. White supremacist. Misogynist. Executioner of hippie culture. Embodiment of evil. These are just some of the ways Charles Manson, the notorious 1960s killer and cult leader, has been described in the countless obituaries published since his death at 83 on Nov. 19.

Manson died unrepentant and incorrigible, and his passing will likely intensify America’s decades-long fascination with its most famous mass killing. But while the Manson murders have many irresistible elements—drugs, sex, celebrity, brainwashing—a big part of Manson’s undying legacy is the versatility of his own story. He is whatever you want him to be; he defies many narratives, and yet fits so many. In fact, no one put it better than the man himself (with a healthy dose of his signature manipulation): ”I am just a mirror,” Manson said several times in a 1970 interview with Rolling Stone. “Anything you see in me is you.”

Evil or human?

“The name Manson has become a metaphor for evil, and there’s a side of human nature that’s fascinated by pure unalloyed evil,” Vincent Bugliosi once said. Bugliosi, the prosecutor on Manson’s case, authored the definitive account of the murders, 1974’s Helter Skelter.

The Associated Press obituary of Manson features the word “evil” three times, including one description of Manson’s image as the “personification of evil.” Linda Kasabian, one of Manson’s disciples and the prosecution’s star witness, also famously called Manson “the devil” in her testimony. Understandable, considering he managed to conjure a murderous frenzy in his followers that left an 8.5-month pregnant woman dead of 16 stab wounds.

Others see Manson as more of a product of his circumstances: a tragic childhood, a neglectful teen mother, relatives who tortured him, and a juvenile-detention system that spat him out abused. “Manson, though, was no devil but a human being, as his death makes clear,” David A. Ulin writes at The Los Angeles Times. ”I don’t say that to soften or absolve him. But I don’t believe in demons; people are frightening enough. Indeed, to accept Manson as a person, to see him through the filter of his humanity, is to acknowledge what we resist: that he was perhaps not so utterly different from the rest of us.”

A product of a culture—and its executioner

Personal biography aside, Manson is also widely seen as a product of his era. He wore his hair long, was obsessed with The Beatles, and hung out with one of the Beach Boys. Manson’s disciples were drifters who started a commune, where drugs flowed freely and sex was unconstrained. “For many, the Manson episode validated their fears of the counterculture movement,” writes David Smith, a physician who treated the Manson family, in the Washington Post. Smith says San Francisco’s “Summer of Love” and embrace of drugs wrought Manson.

But Manson also took advantage of that culture, perverting it to suit his ideas—perhaps this is why he’s also credited with killing the era he came out of. As Joan Didion wrote in her essay “The White Album,” no one was surprised after hearing the news of the murders. “The tension broke that day,” she wrote. “The paranoia was fulfilled.”

Eco-warrior and white supremacist

Manson obits from both sides of the political spectrum proffered still more narratives—that of a leftwing nut job, and that of a white supremacist. Infowars reminded the world that Manson “embraced environmentalism as a justification for his insane actions” and claimed that his preachings about annihilating humanity for the sake of the natural world have been “adopted by the far-left.” (It’s true that Manson spoke about his climate change beliefs several times. In 2011, he even gave an interview to the Spanish edition of Vanity Fair, in which he warned of melting polar caps.)

Breitbart devoted a whole section of its obituary to Manson’s connection with militant leftist group The Weather Underground, and Geraldo Rivera, who conducted an “epic” (his word) interview with Manson in 1988, wrote that Manson was “more popular than Che or Mao….a charismatic snake charmer, an articulate, eco-friendly homicidal maniac who was part Jim Jones and part Adolf Hitler.”

Meanwhile, multiple mainstream, left-leaning or minority-focused publications zeroed in on another, opposing interpretation of Manson’s politics: He was a white supremacist who wanted to wage a race war.

“Mr. Manson was not the end point of the counterculture,” Baynard Woods writes at The New York Times (paywall). “If anything, he was a backlash against the civil rights movement and a harbinger of white supremacist race warriors like Dylann Roof, the lunatic fringe of the alt-right.”

These narratives often seem to be mutually exclusive, but Manson is a universal villain: Suggestions that Manson was embraced by some members of the counterculture are not without merit, nor are assertions that he used race to sow conflict.

America’s patient and entertainer

Described as everything from “wild-eyed” to demonic, Manson seems to demand psychological diagnosis. After all, a “crazy” murderer is more comforting than one who is a rational actor, opportunist, and master manipulator. (Or, as Vox put it, “an average narcissist who practiced social engineering and learned to use the bodies of willing women around him as a bargaining tool.”) In this way, Manson helped usher in an era of fascination with true crime and serial killers, psychoanalysis of whom still provides endless entertainment.

In 2012, Gawker’s Rich Juzwiak even suggested that Manson’s entertainment value could be seen as a redeeming quality. “The world would have been a better place without Manson,” he wrote, “but since he had to exist, his roles as the nutjob to end all nutjobs can be read as something like compensation.” Juzwiak called Manson a “very contemporary celebrity.”

Indeed, our continuing fascination with Manson, whose list of victims is much shorter than most mass killers today, is perhaps most enabled by our cultural obsession with celebrity. “Reality TV and general cultural narcissism have conditioned us to appreciate characters (especially villains) and, man, is that guy a character,” Juzwiak wrote. Or as Manson himself said: “You’re creating a legend, you’re creating a beast, you’re creating whatever you are judging yourselves with into the word Manson.”