The UK has officially resigned itself to dismal productivity growth

In the UK, productivity growth has been almost non-existent for the past decade. But this didn’t stop the government from persistently forecasting that this would correct itself in the near future.

In the UK, productivity growth has been almost non-existent for the past decade. But this didn’t stop the government from persistently forecasting that this would correct itself in the near future.

No longer.

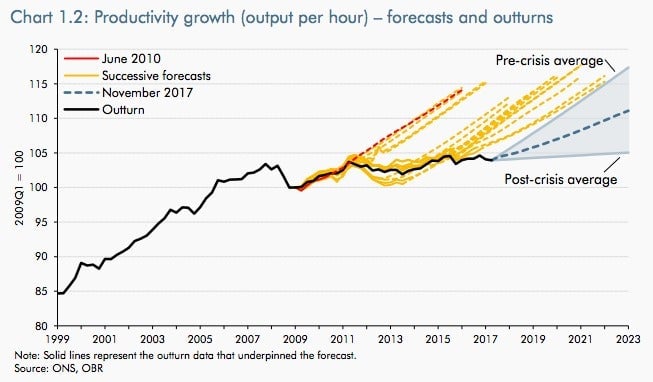

Before the global financial crisis, productivity gains propelled the UK economy. After slipping in 2008 and 2009, nearly a decade of forecasts by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) predicted labor productivity would return to its pre-crisis trend of about 2%. This hopeful stance supported assumptions that the government would take in more tax receipts and reduce the budget deficit. But the actual data never co-operated.

Today, the UK finally gave up on its hope for a productivity recovery. The OBR now forecasts sharply lower output per hour over the next five years than it did in the spring. In turn, it also downgraded forecasts for business investment and economic growth. In 2019, the year the UK is scheduled to leave the EU, GDP growth is forecast to be 1.3%, down from a prediction of 1.7% in March.

This downgrade didn’t come out of the blue. Last month, when the OBR published its annual review of its forecasts (pdf), the official forecasting body said that its projections for productivity had been too optimistic. “Even this relatively pessimistic view – that the financial crisis had done permanent and large, but not increasingly large, damage to the economy’s productive potential – has not been pessimistic enough,” said OBR chairman Robert Chote (pdf).

In parliament, UK Chancellor Philip Hammond said today in his budget speech that the central mission of the Treasury was to raise productivity. He went on to announce plans to increase the size of a “productivity fund” to £31 billion, while putting aside more than £500 million “in a range of initiatives from artificial intelligence, to 5G and full fiber broadband.”

Low productivity growth is a problem shared across many developed countries. Even so, the UK’s problem is particularly severe. Among G7 countries, only Italy has experienced slower productivity growth over the past decade. In 2016, the UK’s gap between output per hour now and what it would have been without the crisis was 15.8%, the biggest shortfall in the G7 and almost double the average of 8.8% across the rest of the group.

There is no simple answer why productivity growth has been so poor; a debate has raged among economists for years. There are a few prominent assumptions. One is that in the UK business investment has been too weak. For example, in the UK there are only about 33 robots installed per 10,000 employees (pdf) in general industry (which excludes the auto sector). South Korea has 411 robots per 10,000 workers, Japan has 213, and Germany 170. In a similar vein, British businesses invest about £1.70 in R&D to every £1 the government invests. By comparison, the US invests about £2.70 and Germany about £2.40.

Another theory is that low interest rates have been propping up zombie companies, trapping people in unproductive jobs at companies that wouldn’t be able to finance themselves at normal interest rates.

Others argue that productivity isn’t being counted properly. Productivity is measured by dividing national income by hours worked, or the number of workers. Diane Coyle, an economist at the University of Manchester who is working on efforts to reconsider how GDP is measured, says statistics have always been bad at measuring human gains from innovation and technological advancements.

The Bank of England argues that measurement issues might only explain a portion of the productivity gap, possibly about four percentage points. Overall, output per hour would still fall short of its supposed potential, even accounting for this. For years, UK economic growth has been instead bolstered by rising employment. But employment levels are now the highest on record and there’s little room to increase growth by simply adding more workers. Without productivity growth, wages won’t rise either, and right now the UK is stuck in the worst decade for pay growth in a century and a half.

As the UK prepares to leave the EU, the OECD noted recently that uncertainty around Brexit has dented business investment and was “compounding the productivity challenge.” The organization warned that Brexit could reduce total factor productivity in the UK by 3% after 10 years, making a bad situation even worse.

Correction: An earlier version of this article said the OBR March forecast for GDP growth was 1.9% in 2019. It was 1.7%.