Russia’s 2018 World Cup poster holds a hidden message to the West

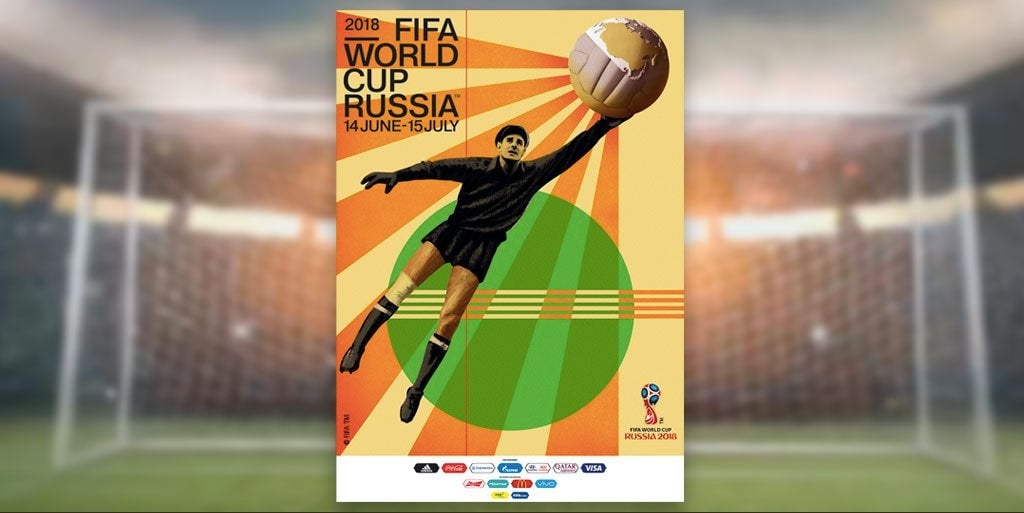

That Russia’s 2018 World Cup poster is a paean to old-school Soviet imagery is clear for all to see. But less apparent are the layers of nostalgia and “great power” symbolism packed within it, as Russia prepares for its second big geopolitical prestige project since the Sochi Olympics: the World Cup.

That Russia’s 2018 World Cup poster is a paean to old-school Soviet imagery is clear for all to see. But less apparent are the layers of nostalgia and “great power” symbolism packed within it, as Russia prepares for its second big geopolitical prestige project since the Sochi Olympics: the World Cup.

The Soviet goalkeeper

In the center flies legendary goalkeeper Lev Yashin, known as the “black spider” for his leaping, spindly appearance and signature black uniform. Undoubtedly the best Russian footballer of all time, Yashin played for the Soviet Union in four world cups, and won the European Championships in 1960 and Olympic gold in the 1956 Olympics. He’s the only goalkeeper to have won FIFA’s Ballon d’Or for player of the year.

The image is much more nuanced than just depicting Russia’s best player, however. Yashin was at the helm of the team at a time when the Soviet Union was cementing its place as a world power in terms of economics, industry, technology—and sport.

Football had been dubbed a “workers’ sport” from the early Soviet period, but the USSR didn’t compete in international competitions until the 1950s. Yashin was the team’s figurehead when they first showed the world their prowess.

He was also playing in a position that had long been at the center of Soviet sporting iconography. Where many countries fetishize the goalscoring striker or the flamboyant midfielder, Soviet art in the 1930s posited the goalkeeper as the quintessentially Soviet heroic underdog.

Unlike the capitalist individualism of a striker seeking personal glory, the keeper stands for collectivism; the unsung hero at the back whose interests are “subordinated” to those of the team, writes academic Andrei Apostolov in a 2014 paper (paywall) on the trope of the Russian goalkeeper.

In heavy-handed allusions to the tensions with Germany that eventually saw the USSR join the Second World War, Stalin-era films characterized the goalie as the “everyman” defender of Russia’s borders against a team of sculpted German aesthetes. Yashin couldn’t have fit the image better, actively cultivating the image of the accessible, “lovable rogue” (pdf, p.3) who came from nothing. Born into a poor Moscow family, Yashin started work in a factory aged 13, and during his career claimed that before every game he had a shot of vodka to tone his muscles and a cigarette to calm his nerves.

He drove the image of the goalkeeper forward just as the Soviet Union’s self-image changed in the 1950s and 60s. More than just the scrappy defender of the gates of Leningrad from Hitler or Moscow from Napoleon, by Yashin’s time the Soviet Union was challenging for global military dominance in the nuclear arms race. In line with the idea of nuclear deterrence as attack as a form of defense, Yashin was revolutionizing the role of the goalkeeper.

Before him, goalkeepers had always stayed back as a last line of defense, waiting for the opposition to shoot. Yashin, on the other hand, would charge around the box and close down attackers, launching his own attacks, and turning the goalkeeper into a “sweeper.”

Yashin’s place at the forefront of an event that president Vladimir Putin is using as a showpiece for Russian power sends several messages, then. As the Kremlin portrays Russia as constantly under attack from Western saboteurs—whether they be NGOs, LGBT people, journalists, or Hillary Clinton—the resurrection of the goalkeeper is an unsubtle symbol of the need to be on-guard.

But let’s not forget attack as a form of defense. Putin is far from the strategic genius that many believe him to be, but, rather, an often effective reactionary counterpuncher. The last time Russia invited the world to its shores, at Sochi, Putin responded to what he saw as a geopolitical sally—the EU signing a trade deal with Ukraine and forcing it to reject Putin’s Eurasian Union—by seizing Crimea and pushing the country into chaos. Its buddying up with the West has largely been put on hold.

Reaching for space: A tech leader once again

Intertwined with the nuclear arms race was the space race—something the new World Cup poster heavily alludes to, with Yashin reaching for a football that transforms into a planet earth seen from space, with Russia on the top.

The space race was the last time Moscow led the world in technology, with America eventually outstripping the Soviet Union in the race to the moon. Now, to escape its dire economic state and return to serious world power, Russia badly needs to diversify its economy and ramp up its tech sector. As such, Putin is reportedly positioning digital progress as a central theme of his 2018 re-election campaign.

The Russian president, who has previously called the internet a “CIA project” and said he “rarely” uses it, began this rebranding attempt in September by visiting the headquarters of Yandex, Russia’s only internet giant. “The aim is clear and unambiguous: Mr Putin offers opportunity; he continues to be the future,” the Independent’s Moscow correspondent Oliver Carroll wrote in a recent piece. The poster screams out that Russians should remember their potential—”Let’s return to the time when the country was the future.”

It’s not much of a stretch to get from there to the Kremlin’s alleged hacking of the 2016 US election, which Russian opposition members hate Americans’ focus on, arguing it reinforces (paywall) a false idea of Putin as an all-seeing geopolitical mastermind. The specter of the space race takes the viewer right back to the time when America was Russia’s enemy number one—something Kremlin propaganda has been pushing since then-secretary of State Hillary Clinton weighed in (paywall) on the side of anti-Putin protestors in 2011.

Just as plucky communists beat rich capitalist Americans during early forays into space, the Kremlin is now believed to have countered the technological might of the US with a ragtag team of criminal hackers, badly-paid trolls, and Macedonian teenagers (paywall). It has succeeded beyond its wildest dreams, sowing chaos in America’s vaunted democratic system—as clear a message as any that the Russian underdog has what it takes to compete.

Constructivist design: Energy, ingenuity, and victory

Central to this messaging is the design itself. There’s no getting away from the fact that the poster harks back to the past while sending a message about the future. But instead of the socialist realism that defined Soviet propaganda from Stalin onwards, with its paternalistic messaging, stolid images, and dull palette, designer Igor Gurovich turned to the most exciting political era and artistic movement in Russian history: the 1920s and constructivism.

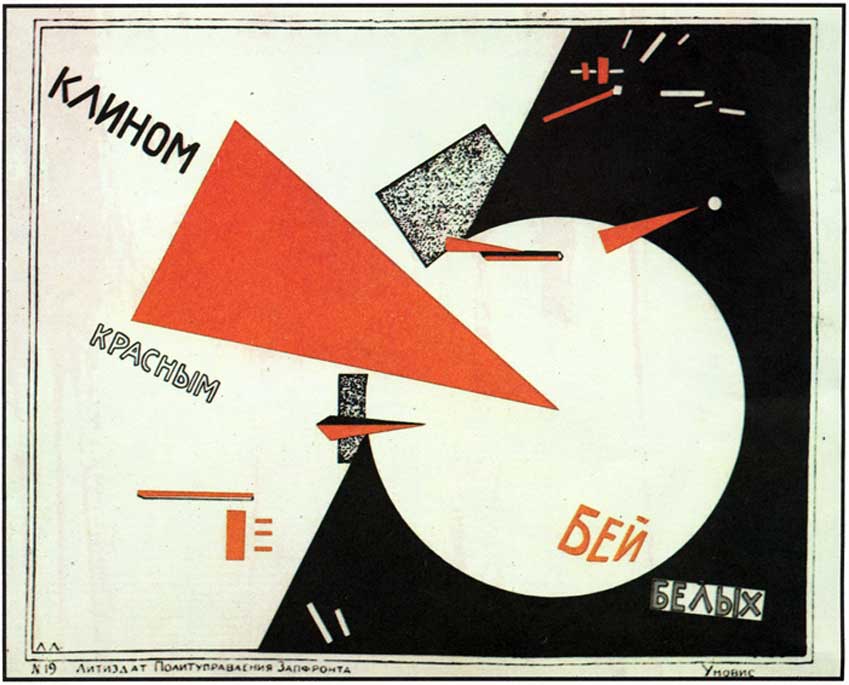

Where the Western Europeans had used cubism to fragment reality in the decade beforehand, Russian constructivists like Kazimir Malevich, El Lissitzky, and Vladimir Tatlin sought to transform it with their searing geometric shapes and vibrant, piercing lines.

The movement thrived off modern materials, the boom in mass production, and the physical rebuilding taking place in industrializing 1920s Russia. For a time, the aesthetic movement received support from the state, which wanted to create a dynamic new consciousness in the new Soviet man—but under Stalin it was deemed too intellectually elitist and fell out of favor.

Constructivism’s visual language “is unquestionably thought of as Russian throughout the world,” Gurovic said at the poster’s launch. “Therefore, in my work on the poster, I really wanted to make this language modern and relevant once again.”

To the outside world, constructivist motifs historically recalled Russian energy, ingenuity, and artistic subversion. But crucially, the poster’s once artistically subversive aesthetic is state-endorsed. It’s a far cry from the truly subversive work of contemporary Russian artists, like Pussy Riot’s screaming attack on Putin in a cathedral or Petr Pavlensky sewing his lips shut outside St Petersburg’s Kazan cathedral in defiance against Russian society’s self-restricting apathy.

Yashin’s triangular shape evokes El Lissitzky’s iconic Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1919). There, the small, sharp, dynamic red wedge of Bolshevism pierces the staid, all-encompassing circle of the bourgeois capitalist Whites. Now, the agile black triangle of a renegade Russian goalkeeper flies over the green soccer field of Western hegemony, with its outdated rules and norms. Smothering it all are rays of yellow energy beaming out of a Russia-topped orb.