AMC is succeeding by breaking the rules of legacy television

It’s good to be AMC Networks right now.

It’s good to be AMC Networks right now.

The season premiere of AMC’s Breaking Bad drew 5.9 million viewers in the United States on Sunday night, double the figure for its premiere a year ago. That kind of audience growth is rare, and it’s even less common for such a dark drama, chronicling the transformation of a chemistry teacher into a ruthless methamphetamine kingpin.

But while ratings are worth celebrating, they aren’t the best measure of success by the weird economics of the television industry. In fact, AMC had prevailed well before Sunday night’s Breaking Bad premiere, and it did so while violating many of the outdated assumptions that tend to govern cable TV.

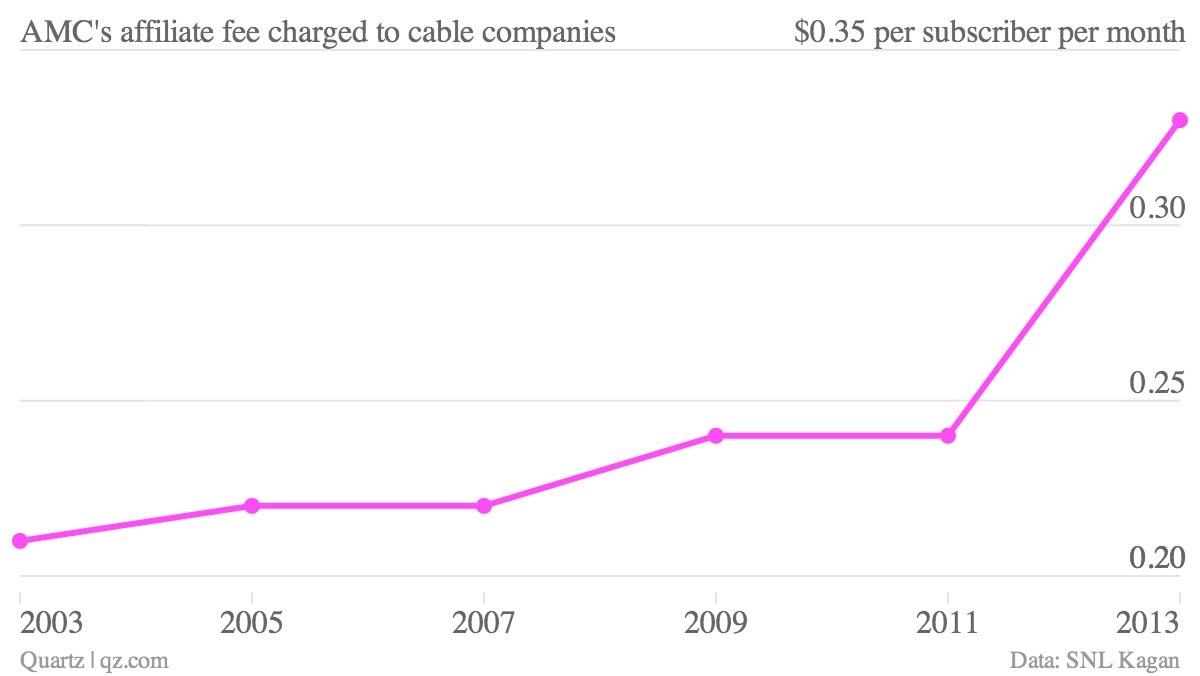

AMC makes most of its money not from advertising but distribution—what it charges cable companies for the right to carry its content. These affiliate fees, sometimes called retransmission fees, are a strong indicator of a network’s worth: The more valued it is by cable customers, the more money it can extract from cable companies. And by that measure, AMC is doing very well, indeed.

The backstory to that chart goes something like this: AMC had been a movie channel—it stood for American Movie Classics—but toward the beginning of last decade, executives worried the network was becoming expendable. Cable companies could provide their own movies more conveniently and for less money.

But Time Warner’s HBO, another network with its legacy as a movie channel embedded in its name, had successfully invested in original programming that made it hard to get rid of. In 2007, The Sopranos aired its final episode on HBO, having changed a lot of assumptions about television in the process. “We need a Sopranos,” was the mantra within AMC.

That year, AMC debuted Mad Men, a drama about an advertising agency in the 1960s. The original script, by a Sopranos writer, had languished for nearly a decade without finding anyone willing to produce it, but risky shows suddenly seemed like better bets. “My boss has told me that ratings, in that moment, don’t matter,” recalled Rob Sorcher, an executive who was brought in to turn around the network.

What AMC got from Mad Men was a different kind of hit, the type that tends to be called “critically acclaimed,” a show that some people would be passionate about—and complain loudly if their cable company ever dared to pull it off the air.

Mad Men was followed a year later by Breaking Bad. Its lead, Bryan Cranston, won the Emmy for best actor after the first season. “Now we’re a network,” Charlie Collier, the president of AMC Networks, remembered saying when Cranston won. “We have two shows.” Popular shows that followed included The Walking Dead and The Killing, which attracted better ratings and additional cult followings.

That provided enough leverage for AMC to demand that cable companies pay higher affiliate fees, which rose from 22 cents per customer per month in 2007 to 33 cents in 2013—a 50% jump in five years, according to estimates by SNL Kagan. (That’s just for AMC itself; AMC Networks also includes IFC, WE tv, and the Sundance Channel, which command lower rates.) When Dish Network balked at paying higher fees last year, AMC ultimately won the dispute.

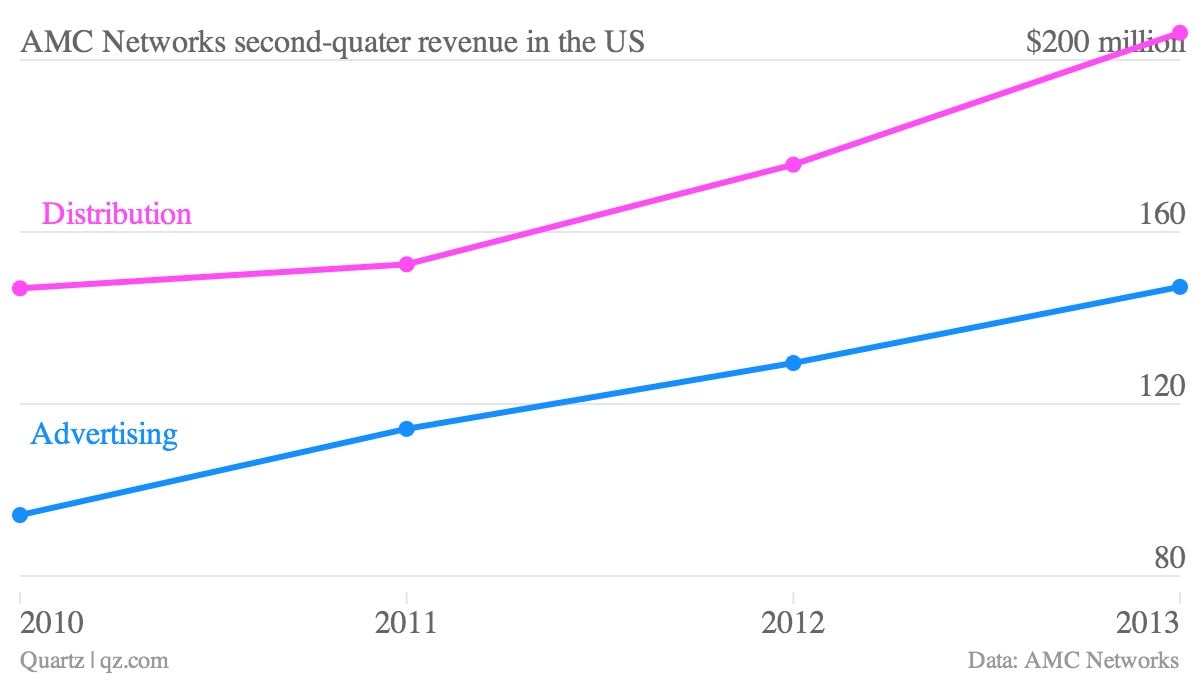

Look at where AMC Networks’s revenue has been coming from lately. Advertising is strong, up 13.7% in the second quarter from a year earlier after faltering in the early years of AMC’s transition. (Mad Men, ironically, did not bring in lots of ad dollars in its first few seasons; zombie drama The Walking Dead proved to be a better sell.) Meanwhile, revenue from domestic distribution—that is, affiliate fees—is even stronger, up 17.5%.

Shares of AMC Networks are up 93% since the company, previously owned by Cablevision, went public in the middle of 2011. Its turnaround is all the more notable because it has bucked a lot of industry norms in the process.

AMC is more progressive than nearly any other cable network (other than HBO, which is in a whole other class) in distributing shows over the internet. New episodes of its most valuable programming, including this final season of Breaking Bad, can be purchased on Apple’s iTunes and Amazon’s Instant Video a few hours after their initial airing on US television. Most cable programming isn’t similarly available, out of fear that people won’t see a need to pay for cable TV subscriptions.

AMC’s policy has rattled cable companies, but the network persists. It struck a deal with Netflix to stream all previous episodes of Breaking Bad, a strategy that, by the industry’s traditional thinking, could have discouraged live viewing of the new episodes. Instead, the opposite seems to have occurred, with summer binge-watching of earlier seasons preparing a much larger audience for the final eight episodes on live television.

Pressing still further, AMC is giving new Breaking Bad episodes to Netflix viewers in the United Kingdom right after they air in the US, instead of the weeks-to-months delay that is typical for exporting top-flight US shows. The partnership could point to other ways for AMC to distribute its programming a la carte rather than in cable bundles, especially outside the US, where it is less constrained.

That posture is aggressive but prudent at a moment when at least three technology companies—Intel, Google, and Apple—are known to be negotiating with content companies like AMC in the hopes of providing television services that could cut out cable companies in whole or part. The question now seems not to be whether such a vision will come to pass, but how quickly. And it wouldn’t be surprising if AMC were more willing to make that leap than some of its rivals, transforming yet again, this time from a cable network to—who knows what to call it?

“If you don’t know who I am,” Cranston’s character Walter White advises an adversary at the end of Sunday’s premiere, “then maybe your best course would be to tread lightly.”