Chinese students blanket the world, but Americans barely get past Europe

In the ongoing debate about the value of a semester abroad, new numbers show that the world’s two superpowers have picked sides.

In the ongoing debate about the value of a semester abroad, new numbers show that the world’s two superpowers have picked sides.

The most recent data from the Institute of International Education shows that nearly 325,500 US students–or roughly 5% of Americans in higher education–received credits from foreign institutions in the 2015-16 academic year. For Chinese students, that number was 1.08 million in 2016, according to Chinese Ministry of Education.

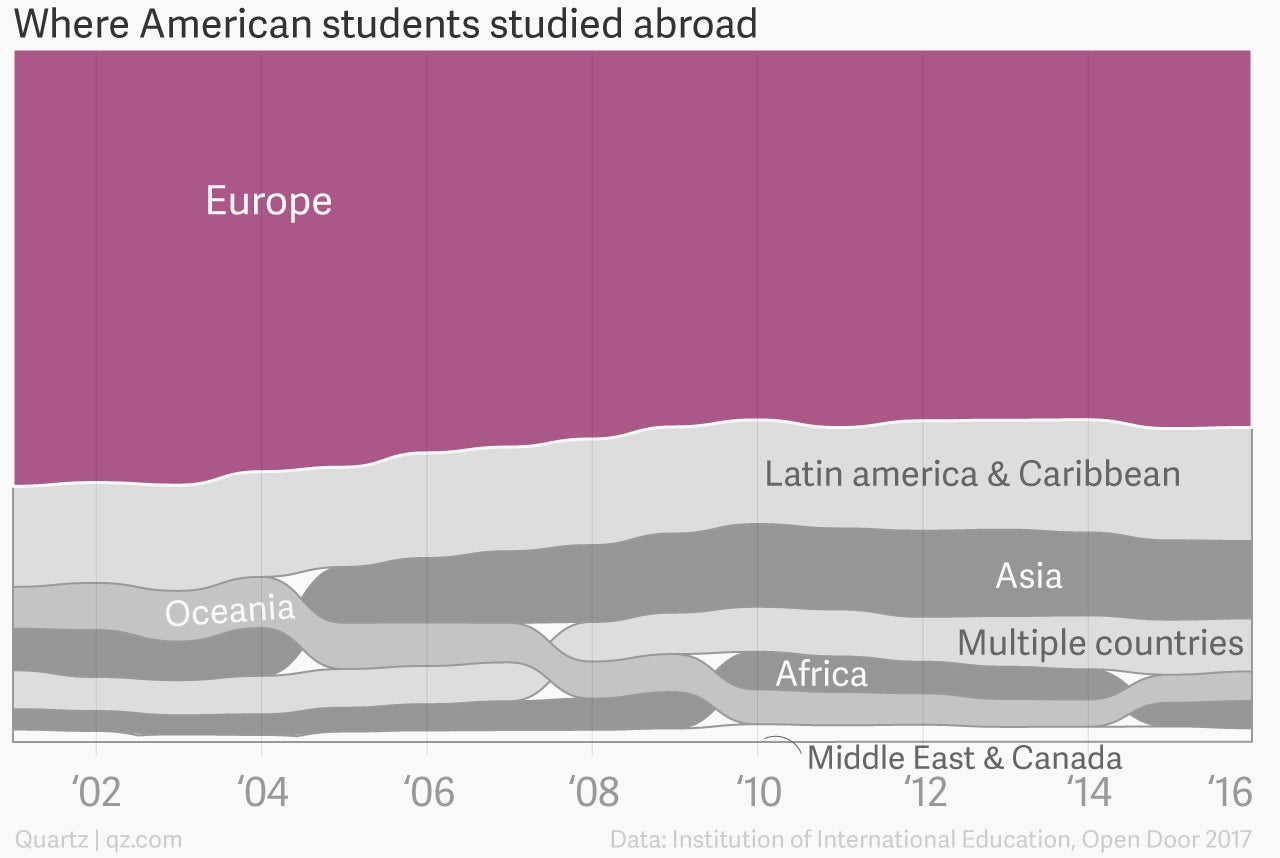

For the privileged 5%, European nations were the “gold standard”, chosen by 55% of all US students last year. Twelve percent picked the UK, the top destination for decades.

When choosing where to spend a semester abroad, US students seek the familiar. In Europe and the UK they can be immersed in a different culture, but not one so different from their own, and stay for a discreet period of time, though not too long– one semester or a summer term is perfect.

Mastering language, though, is a barrier to entry which students are hesitant to push beyond. We looked at data from the Foreign Service Institute, which puts world languages into four categories based on how long it takes for a native English speaker to learn them: from easiest (Spanish, French and Italian) to extremely difficult (Arabic, Chinese and Japanese), and the countries US students were studying in.

The numbers show that more than two-thirds of Americans went to English-speaking countries or countries that speak languages easiest to master. Only 22% of US students picked destinations with a dominant language that takes more than 36 weeks to learn.

Chinese students, however, are not looking to “see the world”, but rather, to gain traction in the global job market. They are not daunted by traveling immense distances away from family, enroll in large numbers in degree programs, and have no choice but to readily embrace different languages.

With the exception of South Korea, which has the largest share of foreign students from China, Chinese students easily travel upwards of 4,000 miles for their education, to countries where the primary language is not one they grew up speaking.

By comparison, in a 2015 survey (pdf), most US students said that their aspirations for studying abroad were to have fun traveling and explore different cultures. That may be fine in the short-term, but not so much in the long-term, when they start interviewing for jobs and find they are competing for the same positions with their fellow exchange students–from China.