Americans have forgotten how to protest

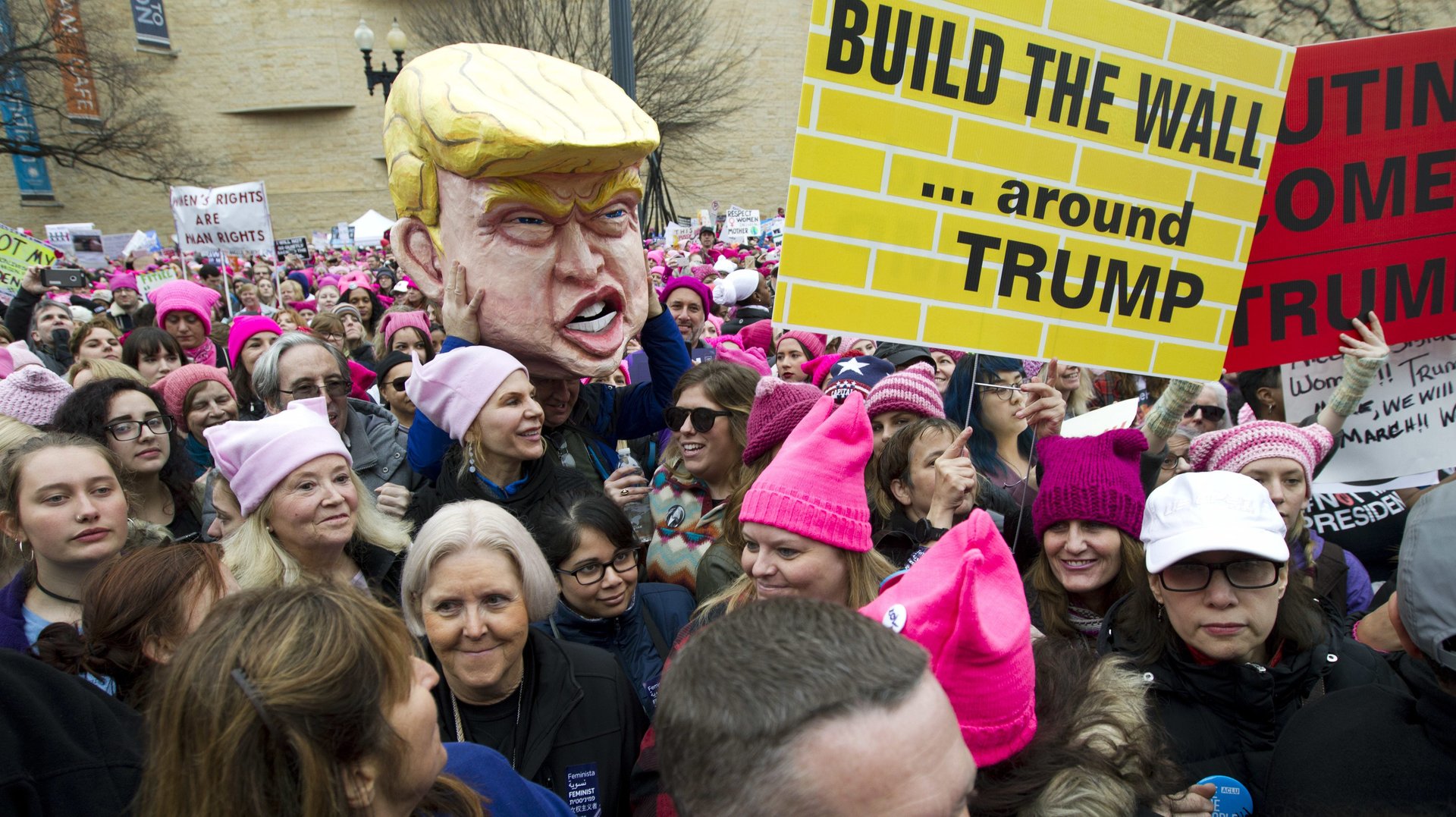

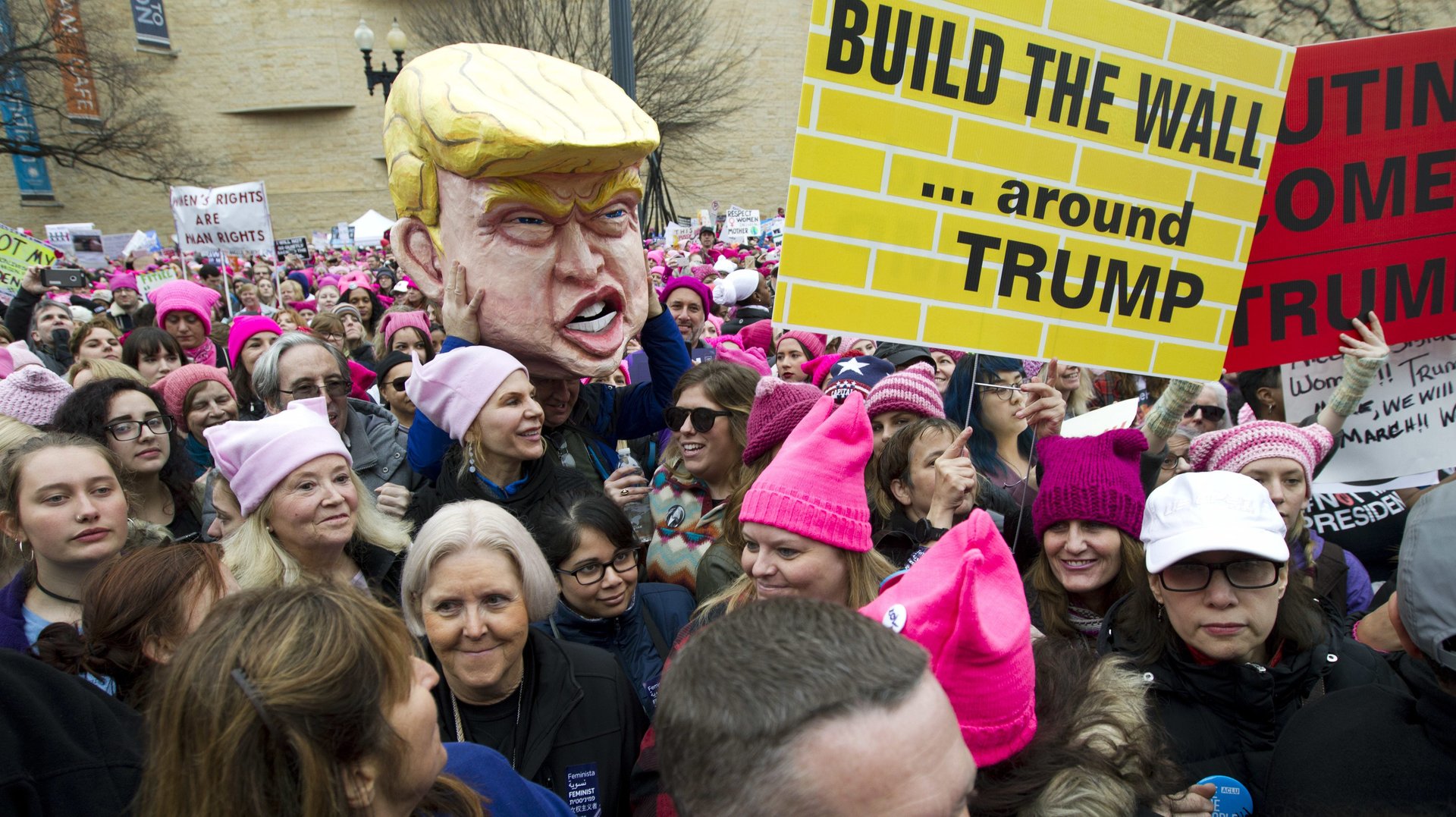

In the days immediately following Donald Trump’s election, thousands of Americans took to the streets with the slogan “Not my president.” That was the so-called “resistance,” which would also take the form of the women’s march, the science march, and other protests across the country.

In the days immediately following Donald Trump’s election, thousands of Americans took to the streets with the slogan “Not my president.” That was the so-called “resistance,” which would also take the form of the women’s march, the science march, and other protests across the country.

Back then, total resistance seemed a little premature; Trump was a democratically elected president whose government had yet to show what it could do. Several months later, the presumably liberal voters who marched against Trump’s election have plenty of reason to protest.

In his first year in office, Trump has been accused of obstruction of justice, endorsed an alleged child molester for senate, and seen his presidential campaign come under investigation for colluding with a foreign power. Seventeen women have accused the president of harassment or assault. And while he refers to himself as the people’s favorite president, Trump has the lowest approval rate of any president in modern history, by quite a margin.

Yet the streets are empty. A follow-up Women’s March is scheduled for Jan. 20, but sustained “resistance” among concerned citizens has been weak, and Congressional attempts to start the impeachment process have failed to gain momentum. Perhaps tired by the frequency and regularity of Trump’s wild pronouncements, Americans seem to have gotten used to shaking their heads rather than rallying in response.

Last month, Daniel W. Drazer argued in The Washington Post that investigation or impeachment were flawed ways to make Trump leave the White House. He writes:

For Trump to lose properly, it has to be at the ballot box. Trump has to run for reelection and be repudiated by American voters. He has to lose the popular vote again, get trounced in the electoral college, and see his party pay the consequences of backing the most ignorant, illiberal president in modern American history.

Drazer makes an important point: Democracy knows no tool more powerful than popular dissent, as Alabama’s electoral rejection of Roy Moore shows. But popular dissent doesn’t only happen at the ballot box, and democracy doesn’t just come alive every four years. Just as citizens can call their representatives to support or oppose a certain law at any point in the electoral cycle, they can also call to request a motion to have the president impeached. To make their point, they can also get back in the street.

As Martin Luther King Jr. wrote in his 1963 letter from Alabama’s Birmingham Jail, spontaneous organization by citizens is powerful not because it replaces political process, but because it fosters “such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored.”

During the civil rights era, King showed Americans the power of public protest. Marches like 1963’s March on Washington, and the Selma to Montgomery march of 1965 revealed the energizing, cathartic power of popular demonstration, creating indelible images of struggle and forcing the government to respond.

The fight was historic, and hard: King and other civil rights heroes stood up against actual violence to gain recognition of their basic rights. The stakes aren’t quite that high today, but public protest works even to express simple discontent.

History is full of examples when the sheer number of people demanding that a leader’s resignation became too big to ignore: Italian women got Silvio Berlusconi to resign in 2011, the same year, Egyptian protestors played a major role in the downfall of Hosni Mubarak. In Ukraine, 2014’s Euromaidan protests felled a whole administrative class, and in 2016, thousands of demonstrating South Koreans were instrumental to the president’s impeachment. These were movements of citizens who could not wait for the process and politics of criminal investigations or electoral defeats—what King described as “legitimate and unavoidable impatience.”

Trump keeps testing his limits, and the American people have a responsibility to make sure checks and balances are working. While Trump treats the Oval Office like a reality show, liberal Americans watch with horror, a captive audience. But true democracy is participatory; it’s the citizens themselves who are responsible for getting off the couch either to cheer on the administration on or turn it off.