200 years of books prove that city-living has made Americans more materialistic

UCLA researcher Patricia Greenfield has long suspected that the environment around us influences our psychology—not in the classic sense that our family life or peer groups sway our behavior, but in a much broader way. Human psychology adapts differently, she theorized, to rural settings than to urban ones.

UCLA researcher Patricia Greenfield has long suspected that the environment around us influences our psychology—not in the classic sense that our family life or peer groups sway our behavior, but in a much broader way. Human psychology adapts differently, she theorized, to rural settings than to urban ones.

Rural living, with its subsistence economies, simpler technologies, and close-knit communities, demands of people a greater sense of deference to authority and duty to each other. Urbanization, on the other hand, generally comes with greater wealth and education, and complex technology and commerce. Adapt to life in a city, and a different set of values becomes more important: for starters, personal choice, property accumulation, and materialism.

“When you have greater wealth, you have more choices,” Greenfield says. When you live in a city, there are simply more paths to chose, more things to do, more ways you might spend your money. Greater education brings choice, too. In this way, personal choice—and an emphasis on the individual—becomes more central in an urban world to our values, our behavior, and our culture.

This implies that as a society slowly urbanizes over time, its psychology and culture change, too. But Greenfield hasn’t been able to prove that until now. In her latest research, published in the journal Psychological Science, she leverages an enormous quantifiable dataset on American culture over the last two centuries that never existed before: the Google Books Ngram Viewer.

Greenfield’s theory borrows from psychology, sociology, and anthropology. But the evidence mostly comes from literature, a collection of 1,160,000 English-language popular and academic books published between 1800 and 2000. If American culture and psychology grew more individualistic as the country urbanized, wouldn’t that transformation be clear in the words from American books (and the concepts that lie behind them)?

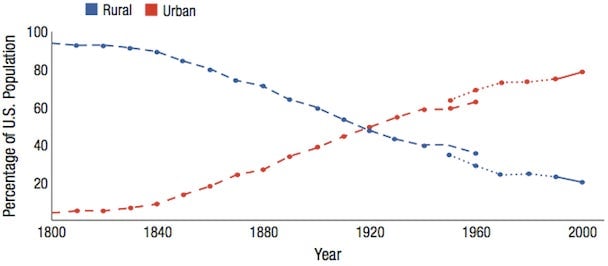

Over these two centuries, America dramatically shifted from a rural country to an urban one, as this graph from Greenfield’s paper illustrates:

“The Changing Psychology of Culture From 1800 Through 2000” by P. Greenfield in Psychological Science. The Census Bureau used two different definitions for “urban population” in 1950 and 1960.

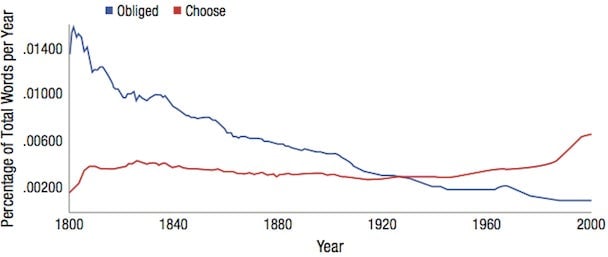

Google’s Ngram Viewer makes it possible to similarly chart over time the prevalence of certain words in a large corpus of books (as a percentage of the total words published in any given year). Greenfield selected several high-frequency words reflecting underlying concepts in psychology. “For example,” she writes in the paper, “‘choose’ was utilized in preference to ‘want’ because freedom of choice is, by definition, a defining attribute of individualism.”

Here, Google’s tool maps the prevalence of “choose” through all these books in comparison to the rough antonym “obliged”:

Greenfield also tested two related nouns: “decision” (as opposed to “choose”) and “duty” (as opposed to “obliged”) with fairly identical results.

“What really surprised me was the replicability,” she says of the results. To prove that she wasn’t just cherry-picking words that happened to prove her point, Greenfield tested different synonyms and even repeated the experiment on a smaller scale with British books over the same time period.

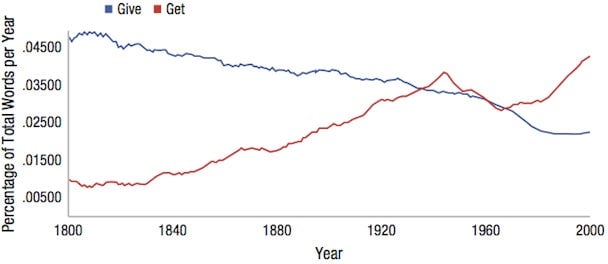

In this next graph, the words “give” and “get” reflect the contrast between contributing to the larger collective (in a more rural society) and obtaining things for one’s self in a more urban one:

Related nouns tested were “benevolence” and “acquisition.”

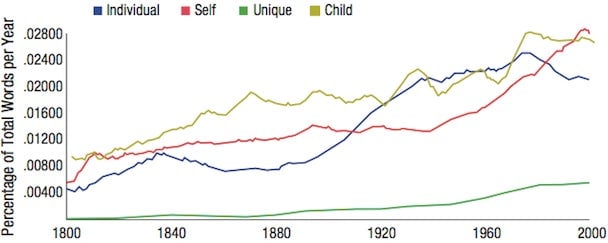

Here, Greenfield graphs the related rise of child-centered socialization, and the importance of the individual…

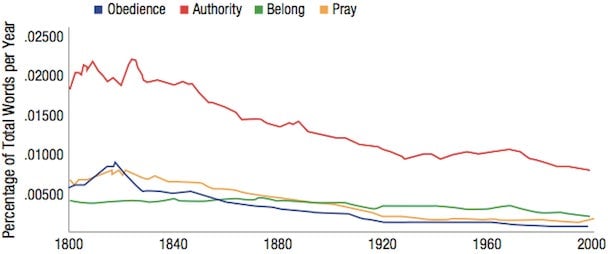

… and the decline of words reflecting obedience, authority and religion:

The cumulative results suggest that there’s something more deep-rooted underway here than the simple life cycle of words that happened to go in and out of style for reasons entirely unrelated to society’s changing values.

But in some ways, this story of the rise of the individual, at the expense of the collective, appears to contradict the idea that cities force us to rely on each other. In politics, for instance, individualism is often celebrated as a virtue of rural living. In cities, by contrast, we must rely on shared parks instead of private back yards (or farms), and shared subway cars instead of private cars.

But Greenfield says that kind of communal subway experience is different from the one early farmers experienced in rural America when whole communities got together to raise a barn.

“We’re talking about a crowd of individuals, we’re not talking about interdependent people,” she says of your morning commute. In the rural society that she is contrasting here, people know each other. In urban society, many of the people you encounter are interchangeable. Your fellow commuters are different (most days). “Even though a policeman comes to help you,” Greenfield says, “you don’t even know his name.”

This doesn’t exactly mean that cities make us egocentric. Culture changes as a result of numerous related processes, including the rise of wealth, education and technology.

“It’s really not just urbanization,” Greenfield says. “It’s all the things that go with urbanization, too.”

Emily Badger is a staff writer at The Atlantic Cities.