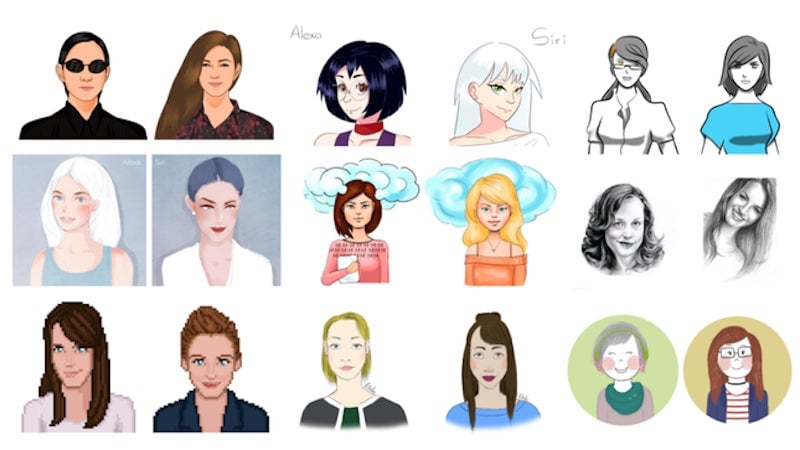

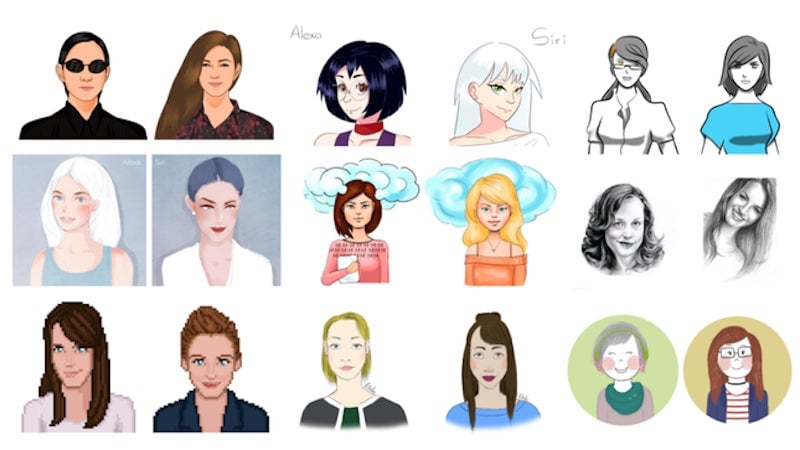

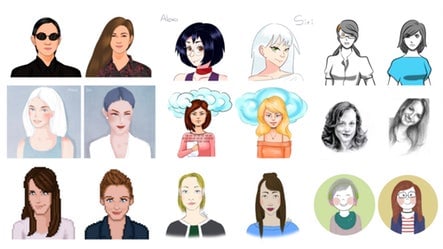

What Siri and Alexa might look like, according to artists

Behind every interface, there’s a designer. More like a team of them. And those designers have a lot to consider: What should Siri sound like? What kinds of things will people ask Alexa to do? How will users expect the Kuri robot to respond when they crack a joke?

Behind every interface, there’s a designer. More like a team of them. And those designers have a lot to consider: What should Siri sound like? What kinds of things will people ask Alexa to do? How will users expect the Kuri robot to respond when they crack a joke?

We have become accustomed to relating to these interfaces, and increasingly they are able to relate to us—taking in the world around them, talking to their users, and even inferring our emotions from how our faces change shape. I call this layer an Affective User Interface (AUI), a term borrowed from the field of Affective Computing.

Affective Computing is a field of computer science that develops technology that we might consider intelligent and emotionally aware. These new interfaces present a slew of opportunities and challenges because, as Dr. Cynthia Breazeal of the MIT Media Lab points out in her book Designing Sociable Robots, when a technology “behaves in a socially competent manner,” our evolutionary hardwiring causes us to interact with it as if it were human.

And once we enter into that relationship, the personas we design for these bots affect our behavior, too. I’ve heard many people say that unassertive bots often bring out the worst in kids. When there are no social checks on rudeness—bots don’t tattle, after all—children tend to be more blunt, and can even become abusive.

That lack of assertiveness also affects adults. Reporter Leah Fessler researched how female-gendered bots respond to sexual harassment. It turns out that the assistants’ permissive personas can reinforce some disturbing stereotypes about women, and allow the user free reign to degrade them at will.

If bots can have a gender, I started to wonder whether they might also have a cultural or even racial identity. Considering the fact that these products allow us to choose between various accents, it would seem that designers have created nationalities for our bots.

I’m certainly not the first person to surface these issues. This (paywall) New York Times piece by AI Now’s Kate Crawford on how “Artificial Intelligence’s White Guy Problem” comes to mind. And there are many people here at IDEO who are thinking through what it means to be inclusive human-centered designers as we work on Augmented Intelligence projects.

To explore this further, I decided to conduct an experiment to surface the personality of these bots by interviewing them.

The key was to ask soft questions: Where are you from? How old are you? Do you have any kids? What do you look like? Even, Tell me a story.

These interactions were not actionable queries, and thus triggered purely conversational responses that revealed the “personality” that the bots’ creators had designed.

I recorded a video interview with each voice assistant and handed these over to a number of illustrators commissioned via the social gig site Fiverr. While a few of the artists had previous exposure to the bots, I was able to source English-speaking international artists in markets where Alexa and/or Siri were not available. Countries of origin included Indonesia, Pakistan, Ukraine, Venezuela, the Philippines, and the US. For many of them, my videos were their first meaningful exposure.

Here are the images that came back:

Gender came through clearly, but I would also argue that none of the illustrations depict a person of color. Whether they were intentionally designed that way is not the issue. If users perceive the bots this way, what kind of cultural pressures are they carrying into the home?

It’s something I think about a lot as a first-generation American who has worked in and around tech throughout my career. On my father’s side, I’m the second US-born family member, and on my mom’s side, I’m the first. I grew up in a diverse community, and the tapestry of cultures I experienced was simply normal, everyday life.

I was aware of code-switching pretty early on; many of my friends and family had their normal voice and their “professional” voice, and they chose which to use in different environments.

Looking back, I first learned about it when my mom gave a wedding speech. My brother was shocked; he didn’t recognize the voice that he heard. I had to explain to him this was my mother’s work voice. Code-switching isn’t inherently bad—we all do it to some degree—but if we’re to design Affective User Interfaces that are truly human-centered, then we must consider that for some, the switch requires more effort.

If users perceive the bots this way, what kind of cultural pressures are they carrying into the home?

Inclusivity is not just an issue at the bleeding edge of tech. We’re seeing a growing body of evidence that those who speak outside of mainstream vernaculars have a harder time being properly recognized by affective systems.

This represents an accessibility challenge, but one that is resultant from a cultural rather than physical challenge. In a tech industry that is known to be monocultural, we must take steps to ensure our affective systems are not just designed to be useful to their creators, but inclusive of the full spectrum of people their products will serve.

Because ultimately what’s at stake is trust. Studies have shown that when brands lose trust, they lose customers.

As designers, it’s our job to expand the usability of our affective devices to ensure they serve the rich tapestry of people, cultures, and vernaculars they will encounter. Beyond being good design, it’s good for business, because in our affective future, the products that win will be the ones that users trust.