The battle to make French a “gender-neutral language” is emphasizing the country’s inherent sexism

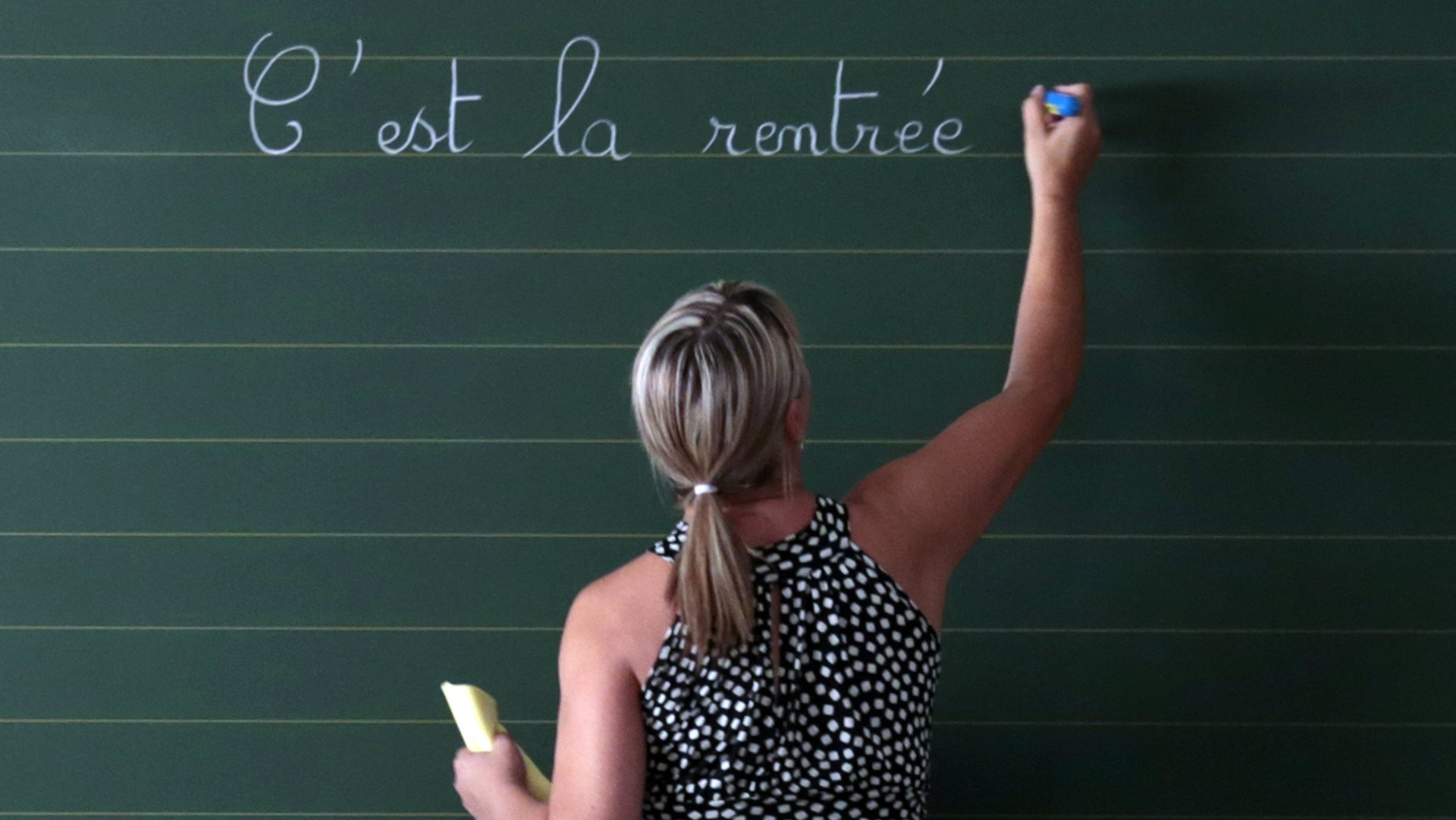

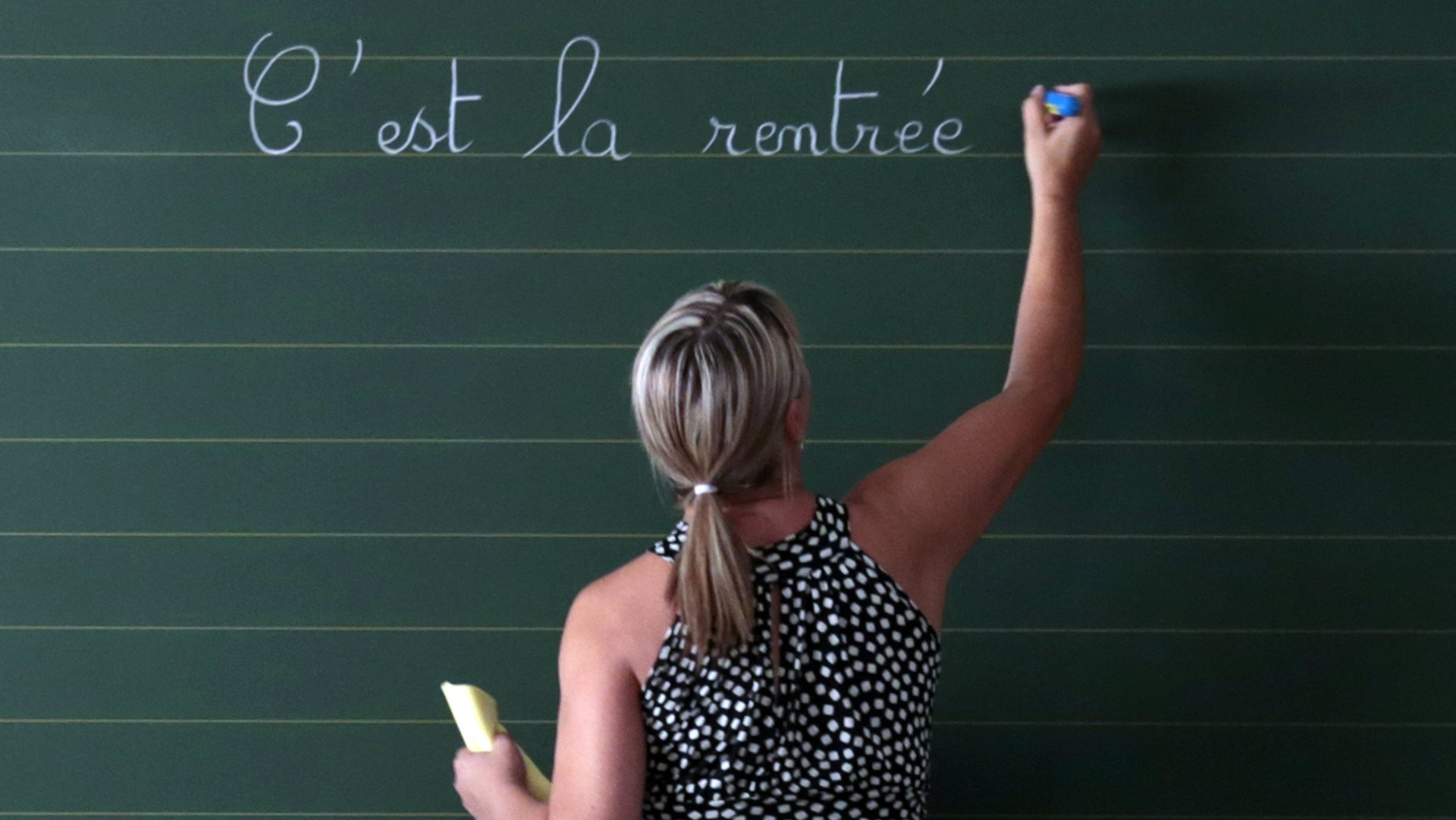

That the French language remains so central to the culture here wouldn’t surprise most people outside the country. Still, having two teenagers in French middle school has taught me to appreciate how profoundly important it remains for people not just to master their language skills, but to perfect them. Whereas the practice of teaching grammar has slowly faded in American middle schools, our kids still spend several hours each week in their French classes learning obscure verb tenses, drilling into the tiniest nuances of punctuation, and striving toward an accent-less speech. One of the most illuminating exercises is the “dictée.” A teacher stands in front of the class and reads aloud a page of text while students furiously copy it down to be graded later on grammar, spelling, and punctuation. It’s impossible for me to imagine a 14-year-old in the United States being subjected to such rigor. The level of eye rolling this would provoke would probably be lethal to the teacher.

That the French language remains so central to the culture here wouldn’t surprise most people outside the country. Still, having two teenagers in French middle school has taught me to appreciate how profoundly important it remains for people not just to master their language skills, but to perfect them. Whereas the practice of teaching grammar has slowly faded in American middle schools, our kids still spend several hours each week in their French classes learning obscure verb tenses, drilling into the tiniest nuances of punctuation, and striving toward an accent-less speech. One of the most illuminating exercises is the “dictée.” A teacher stands in front of the class and reads aloud a page of text while students furiously copy it down to be graded later on grammar, spelling, and punctuation. It’s impossible for me to imagine a 14-year-old in the United States being subjected to such rigor. The level of eye rolling this would provoke would probably be lethal to the teacher.

In sharp contrast, language remains a serious affair in France, where something as trivial as the introduction of a foreign word into casual speech can spark furious public debates among intellectuals as well as regular folks on social media. During the spring campaign for president, the far right denounced Emmanuel Macron for the deeply embarrassing sin of delivering a speech in English while abroad, an act they considered to be borderline treason. The French language, speaking it well, guarding its purity from unwanted incursions or corruptions by bacterial elements that might weaken it, remains an essential battle.

And so it’s hardly shocking that a radical proposal to rethink one of the core principles of the French language has caused an uproar and divided thinkers across the political spectrum. In this case, the debate is even more combustible due to the concept that lies at the heart of the proposed changed: gender. A movement known as “Écriture Inclusive,” what English speakers would call “gender-neutral language,” is calling out the French language for being inherently sexist because it favors the masculine usage. Proponents have outlined a complex, if awkward, remedy that its adherents argue is essential for correcting the subtle ways the French language creates stereotypes that are biased toward men over women.

The release in September of the first gender-neutral textbook for elementary schools that embraced “écriture inclusive” provoked a furious debate and has made this issue number one on the French cultural circuit. One of the groups behind this movement is called “Mot-Clés” (“Key Words”) which has described French as a “phallocentric language” and published instructional material on how to write anew in a way that will motivate a more fundamental shift. “To really change mentalities, we must act on what they are built on: language,” says its website. Even for many on the left, it poses an uneasy choice between their belief in progressive ideals about men and women, and their passion for language.

Somewhat surprisingly in a country where change can be glacial, there have been signs that the movement has been making inroads, which is no doubt what has made the mounting backlash over the past few weeks even more furious. In pressing the case, activists have been met with everything from ridicule to outright contempt to condemnation for daring to not just insult the French language, but to take actions that threaten to undermine everything that it means to be French.

The ensuing hysteria was perfectly captured by l’Académie française, the organization charged with adjudicating all things related to the French language for the last four centuries or so. The academy is one of those elements of French culture that seems almost like it was invented by someone who wanted to write a parody of French culture. It is presided over by members who are called “the immortals”, and each one looks like they responded to a casting call for actors to play the most extreme caricatures of stuffy, conservative, reactionary, and humorless French elites and intellectuals. In late October, the immortals declared that inclusive writing posed a “mortal danger” to the French language. Displaying a willful ignorance of the ascendence of English over the past century, they warned that inclusive writing could make French so complex that it could fall from favor by causing people around the world to learn other, more barbaric languages that were easier.

“In the face of this ‘inclusive’ aberration, the French language is now in mortal danger, for which our nation is now accountable to future generations,” they huffed. “It is already difficult to acquire a language, how will it be if the use adds to it second and altered forms? How will future generations grow in intimacy with our written heritage? As for the promises of the French speaking world, they will be destroyed if the French language weakens itself by this increase in complexity, benefitting other languages that will take advantage to prevail on the planet.”

Language and gender was a hot topic when I was in college about 30 years ago in the United States. We arrived at college in 1987 as freshmen, but we finished as first years. Firemen became firefighters. Garbagemen became sanitation workers. We had debates at the college newspaper about whether to use “he” or “she” or “they” in order to reduce or eliminate gender bias. This was not a straight line, as the US enjoyed its own backlash and the fight against political correctness flared. But as awkward as some of this felt at first, it does force you to think about how language creates stereotypes. And then, after a time, it just becomes normal.

French, like many Romance languages, presents a tougher challenge. As an English speaker learning French late in life, the idea that everything has a gender is a difficult to fully absorb. There are a few tricks, but not many. Knowing the table is feminine and the coat is masculine is just not an intuitive thing for me, no matter how much time I try to spend reviewing the gender of every object. Beyond that, the need to learn the feminine and masculine version of various nouns and adjectives is exhausting. She is an animatrice while he is an animateur. He is Canadian but she is Canadienne. Fortunately for me, they are both a “journaliste.”

Given the profound role gender plays in the language, untangling that knot is tough. On a very basic level, inclusive writing proposes three main solutions. The first is probably the most straight forward and easiest to digest. Where possible, replace general phrases that refer to something about “man” (“homme”), with a gender-neutral word, like “human.” My kids have spent a fair amount of time learning about the “Droits de l’Homme.” (“Rights of man.”) Instead, use “droits humains”. Simple, except of course “humain” is a masculine noun. So then maybe try “droits de la personne humaine.” Because “personne” is feminine, which lets you change “humaine” to its feminine form when used as an adjective. Phew. French is like the older briar patch when its comes to gender: The more you struggle against it the more you become stuck.

The next option is to do what we sometimes did, inelegantly, in English: use both forms. For instance, you can say, “Elles and ils font.” (masculine “they” and feminine “they” make.) It’s not uncommon now to hear a speaker in public begin by saying, “Bonjour à tous…et à toutes.” Or you can try “les membres” (which is still masculine). And for certain words that tend to be the same for masculine and feminine, make greater use of the feminine option. For instance, a man or woman who teaches is a “professeur.” So make greater allowance for “professeuse.”

But then comes the whopper, the one that really ties certain corners of the country in knots: Take a word and include all the possible endings with extra punctuation. So “candidat” (masculine) becomes “candidat·e·s.” Admittedly, it’s awkward to write, and it’s anyone’s guess as to the pronunciation.

Rest assured, this is by far the most divisive of all the parts of inclusive writing, and the one that prompts the greatest derision. Consider this tweet: “Trying to read 130 pages of a report from the economic, social and environmental council drafted using inclusive writing… An idea of torture.”

The backlash has only seemed to embolden advocates. Late last month, the city of Paris’ Green Party requested a change regarding one of the most notable days on the French calendar. The French call their cultural history “Patrimoine”, which includes architecture, general culture, and history. It’s taken very seriously here. Once a year, ancient buildings and museum around the country open their doors to the public for the “La Journée de Patrimoine.”

During the council meeting, ecologist Joëlle Morel rose and proposed the name be changed to “La Journée du Matrimoine et du Patrimoine.”

The leader of one of Paris’ moderate parties wasn’t having it. In a statement, Eric Azière, the group’s president, noted that the last proposal from the environmentalists was for a nudist section in one of the city’s famed parks. “Where are the Greens (adding mockingly “les verts et les vertes”) going next in this fight for equality between the sexes?” he wrote. “We are eager in any case to learn about their next battle for Paris.”

The ceaseless mockery, however, isn’t slowing the tide. Numerous newspapers have started slipping inclusive writing into their headlines. That includes this story from Toulouse’s La Dépêche, which reports on another shocker. Hundreds of teachers signed a petition stating that they would no longer emphasize the masculine over the feminine in their teaching. Their rationale, aside from wanting to promote equality, reveals another one of those profound differences between this country and my homeland, and one that still tickles me. The group noted in their manifesto that the rule emphasizing masculine over feminine was a relatively new one. And by that, they meant it had only been in place since the 17th century. For the French, that makes it practically a current event.

The group said ending this practice, particularly in the teaching of grammar to kids, could have a profound impact on their thoughts about gender:

“Other measures working to express greater equality in the language are necessary, but the most urgent is to stop spreading this formula which summarizes the necessary subordination of the feminine to the masculine.”

But the divisions remain. In mid-November, Macron’s Minister of Education, Jean-Michel Blanquer, addressed the National Assembly on the topic. He pointed out that one of the country’s most treasured words, “République,” is feminine, and the national symbol of France, Marianne, is a woman. He warned that the inclusive writing movement threatened to divide the language. He vowed to be “vigilant, so that there is only one grammar, one language, one Republic.”

The debate over inclusive writing comes after a furious decade of change in which France has tried to fundamentally reset gender relations in the county. Back in 2006, the World Economic Forum ranked France 70th among all countries in terms of gender equality. That was an embarrassing thorn in the side of a country whose motto emphasizes “égalité.”

Part of this lag had to do with how the notion of equality is interpreted. By stating that everyone is equal, by making that Enlightenment notion the center of its post-revolution Republican values, it seemed redundant to have to single out a particular group and say they deserve equality. Because everyone is equal means everyone is equal, right?

Of course, that’s not true in France or anywhere else. While there may have been grudging and belated recognition of that reality in France, the country has been making a mad dash to make up for lost ground. The country strengthened laws on equality in the workplace and quotas for electoral politics. This rhythm accelerated when the Socialist Party came to power in 2012. That year, a Ministry for Women’s Rights was created. And two years later, a sweeping law was passed to further address gender imbalance in the workplace, media stereotypes, parental leave for men and women, domestic violence, and equality in politics.

Those efforts included the creation of the High Gender Equality Council in 2013. While the debate about gender-neutral language had bubbled around the French language for years, the council put it back into play by calling for more attention to the subject in 2014, and publishing a guide about how to implement inclusive writing in 2015.

It was that document which eventually inspired one of France’s most important publishing houses, Hatier Editions, to release the first textbook for the country’s school children in an elementary school that promoted inclusive writing:

And it was the release of this book in September for the 2017–18 school year that inflamed the debate. Speaking on Europe 1, philosopher Raphael Enthoven said teaching inclusive writing to kids amounted to “brain washing” that “impoverishes the language.” The discourse surrounding the topic has only gotten uglier since then.

As an outsider here, it remains difficult to judge just how the country stacks up against my homeland, where the women’s movement that began decades ago had a far greater impact much earlier. Certainly, as we’ve seen this year with the massive women’s marches and the #MeToo movement, nobody would argue that the US has anything approaching true gender equality.

According to “Mots-Clés,” men in France still earn on average 23.5% more than women, roughly about the same disparity as the United States. For all its shortcomings regarding the treatment of women, France does offer things like free universal childcare from the age of 6 months. It doesn’t necessarily define that as a women’s program, but it’s one that certainly gives women who want to return to the workforce an economic and social boost.

Still, there are some expectations, some ideas, that are burrowed so far down into a culture that the people spreading can’t even seem them. Language is certainly one of the culprits that subtly transmits culture and reveals it. A couple of years ago, a French female friend of ours went for a job interview in another city. The female executive conducting the interview seemed a bit surprised that our friend would consider a job that might require her family to move. “Have you really thought about how disruptive that might be to your kids?” she asked our friend. This shocked us, when she recounted it later, though she found it not unexpected.

The good news overall for France is that this flurry of attention seems to be having an impact. That same WEF index now places France 11th overall among the world’s countries for its treatment of women. It’s a standing that likely will be helped in the coming years with the election of Macron, who during the election season in the spring insisted that half of his new party’s candidates for the Assembly be women, and went on to choose one of the most gender-balanced cabinets in the country’s history.

Macron declared in late November that fighting for equality between men and women would be his “great cause” and said that gender inequality was a “national embarrassment.” In a public speech, he said the government would have three approaches: greater education around equality, stronger anti-harassment laws, and more support for victims of sexual abuse. And he highlighted increased budget spending for women’s issues, though none of this seems to changed his education minister’s mind about inclusive writing.

It also hasn’t completely convinced feminists in France. Marilyn Baldeck, a general delegate of the European Association against Violence against Women at Work, told Le Figaro that the “modest” budget increase was a “dusting” and nothing more.

Words are critical and can have a big impact. But in this case, Macron’s skeptics also seem to be saying that sometimes words are just words, and so are not nearly enough. It’s the actions of the president that will count, and determine whether that march toward equality in France continues.

This post was originally published on Medium.