30 years after Prozac arrived, we still buy the lie that chemical imbalances cause depression

Some 2,000 years ago, the Ancient Greek scholar Hippocrates argued that all ailments, including mental illnesses such as melancholia, could be explained by imbalances in the four bodily fluids, or “humors.” Today, most of us like to think we know better: Depression—our term for melancholia—is caused by an imbalance, sure, but a chemical imbalance, in the brain.

Some 2,000 years ago, the Ancient Greek scholar Hippocrates argued that all ailments, including mental illnesses such as melancholia, could be explained by imbalances in the four bodily fluids, or “humors.” Today, most of us like to think we know better: Depression—our term for melancholia—is caused by an imbalance, sure, but a chemical imbalance, in the brain.

This explanation, widely cited as empirical truth, is false. It was once a tentatively-posed hypothesis in the sciences, but no evidence for it has been found, and so it has been discarded by physicians and researchers. Yet the idea of chemical imbalances has remained stubbornly embedded in the public understanding of depression.

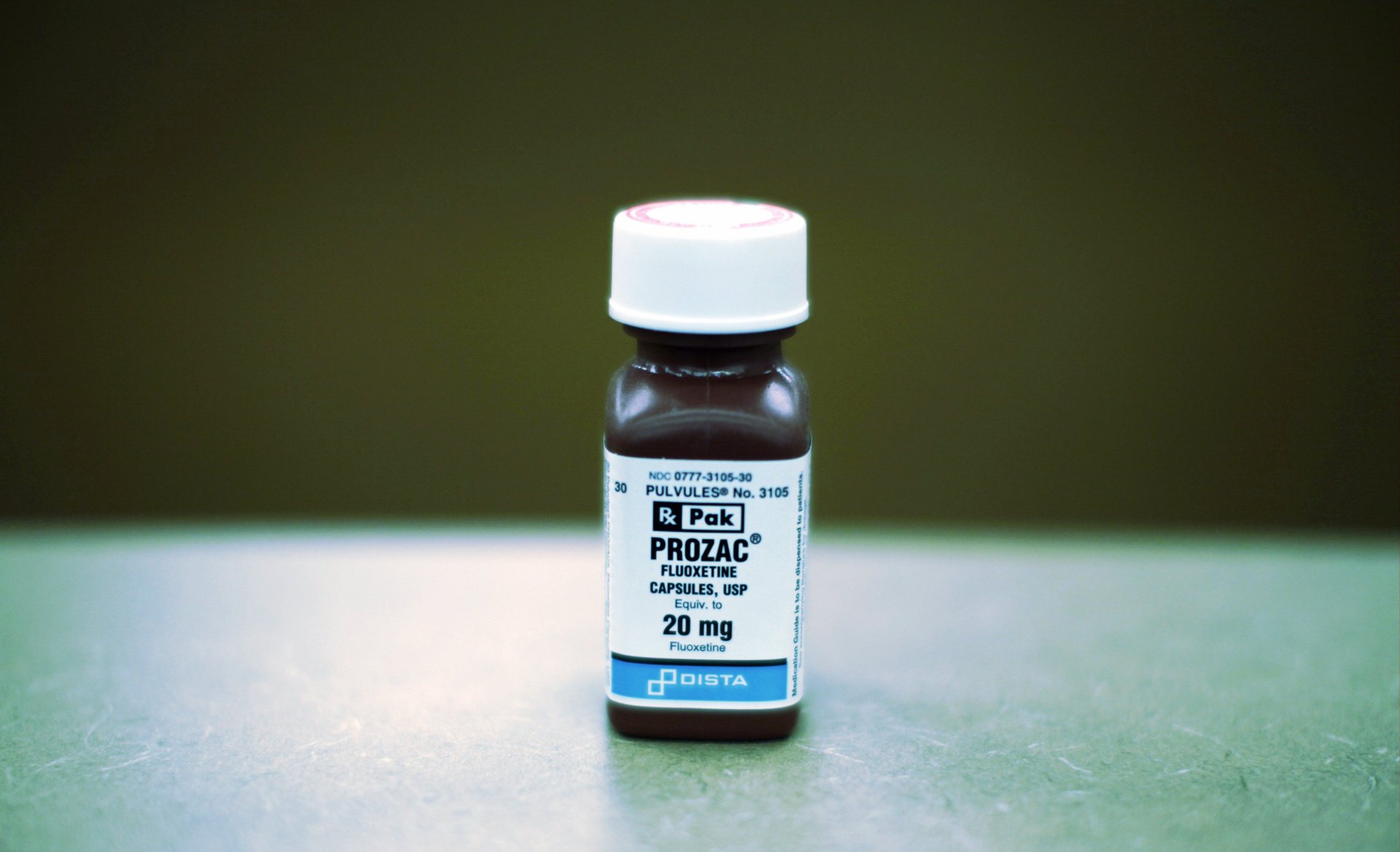

Prozac, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration 30 years ago today, on Dec. 29, 1987, marked the first in a wave of widely prescribed antidepressants that built on and capitalized off this theory. No wonder: Taking a drug to tweak the biological chemical imbalances in the brain makes intuitive sense. But depression isn’t caused by a chemical imbalance, we don’t know how Prozac works, and we don’t even know for sure if it’s an effective treatment for the majority of people with depression.

One reason the theory of chemical imbalances won’t die is that it fits in with psychiatry’s attempt, over the past half century, to portray depression as a disease of the brain, instead of an illness of the mind. This narrative, which depicts depression as a biological condition that afflicts the material substance of the body, much like cancer, divorces depression from the self. It also casts aside the social factors that contribute to depression, such as isolation, poverty, or tragic events, as secondary concerns. Non-pharmaceutical treatments, such as therapy and exercise, often play second fiddle to drugs.

In the three decades since Prozac went on the market, antidepressants have propagated, which has further fed into the myths and false narratives we tell about mental illnesses. In that time, these trends have shifted not just our understanding, but our actual experiences of depression.

* * *

In the two millennia since Hippocrates founded medicine, society has embraced then rejected many theories of mental illness. Each hypothesis has struggled to reconcile how the subjective psychological symptoms of depression map onto physical malfunctions in the brain. The intractable relationship between the two has never been satisfactorily addressed.

Hippocrates’ humor-based notion of medicine, much like contemporary psychiatry, portrayed mental illness as rooted in biological malfunctions. But the evolution from Hippocrates to today has been far from smooth: In the centuries between, there was widespread belief in superstition and the supernatural, and symptoms that we would today call “depression” were often attributed to witchcraft, magic, or the devil.

The brain became the primary focus of depression in the 19th century, thanks to phrenologists. The field of phrenology, which took the shape of the skull as determinant of features of the underlying brain and psychological tendencies, was used by bigots to justify eugenics and has rightly been dismissed. But, though highly flawed, it did advance ideas of the brain still believed today. Whereas other physicians of the time believed organs like the heart and liver were connected to emotional passions, phrenologists held that the brain is the only “organ of the mind.” Phrenologists were also the first to argue that different areas of the brain have distinct, specialized roles and, based on this belief, posited that depression could be linked to a particular brain region.

The attention on the brain faded in the 20th century, when phrenology was supplanted by Freudian psychoanalysts, who argued that the unconscious mind (rather than brain) is the predominant cause of mental illness. Psychoanalysis considered environmental factors such as family and early childhood experiences as the key determinants of the characteristics of the adult mind, and of any mental illness.

“Beginning with Freud’s influence, through the first half of the 20th century, the brain almost disappeared from psychiatry,” says Allan Horwitz, a sociology professor at Rutgers University who has written on the social construction of mental disorders. “When it came back, it came back with a vengeance.”

* * *

A conglomeration of factors, beginning in the 1960s but having the largest effects in the ‘70s and ‘80s, contributed to psychiatry’s renewed emphasis on the brain. Firstly, in the US, conservative presidents disparaged as liberal causes any political efforts to alleviate social conditions that contribute to mental health, such as poverty, unemployment, and racial discrimination. “Biologically-based approaches became more politically palatable,” says Horwitz, noting that the National Institute of Mental Health largely abandoned its research on the social causes of depression under president Richard Nixon.

There was also growing interest in the role of drugs, for good reason: Newly developed antidepressants showed early success in treating mental illnesses. Though Freudian psychoanalysts did use the drugs alongside their therapy, the medication didn’t neatly fit with their theories. And while individuals had previously paid for mental health care themselves in the US, the 1960s saw private insurance companies and public programs, such as Medicaid and Medicare, increasingly take on those costs. These groups were impatient to see results from their investment, notes Horwitz—and drugs were clearly both faster and cheaper than years of psychoanalysis.

Psychoanalysis also rapidly went out of fashion in that time. Organizations such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness, which advocated for the interests of those affected by mental illness and their families, were distrustful of psychoanalysis’ blame on parental figures. There was also a growing distaste for psychoanalysis among those on the left side of the political spectrum who believed psychoanalytic theories upheld conservative bourgeois values.

At the time, psychoanalysis was deeply entwined with the field of psychiatry (the medical specialty that treats mental disorders.) Until 1992, psychoanalysts were required to have medical degrees (paywall) to practice in the US—and most had MDs in psychiatry. “Psychiatry has always had a tenuous position in the prestige hierarchy of medicine,” says Horwitz. “They weren’t regarded by doctors and other specialties as being very medical. They were seen more as storytellers as opposed to having a scientific basis.” As Freudian psychoanalysis became increasingly rejected as a pseudoscience, the entire field of psychiatry was tarnished by association—and so it pivoted, creating a new framework for diagnosing and treating mental health, founded on the role of the physical brain.

The theory of chemical imbalances was a neat way of explaining just how brain malfunctions could cause mental illness. It was first hypothesized by scientists in academic papers in the mid-to-late 1960s, after the seeming early success of drugs thought to adjust chemicals in the brain. Though the evidence never materialized, it became a popular theory and was repeated so often it became accepted truth.

The theory well suited psychiatrists’ newfound attempt to create a system of mental health that mirrored diagnostic models used in other fields of medicine. And the focus on a clear biological cause for depression gave practicing physicians an easily understandable explanation to tell patients about how their disease was being treated.

“The fact that practicing physicians and leaders of science bought that idea, to me, is so disturbing,” says Steve Hyman, director of the Stanley Center for psychiatric research at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard.

The shifting language of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—widely and deferentially referred to as the Bible of contemporary psychiatry—clearly shows the evolution of field’s portrayal of mental illness. The second edition (pdf), published in 1968 (the DSM II), still showed the influence of Freud; conditions are broadly divided into more serious psychoses—with symptoms including delusional thinking, hallucinations, and breaks from reality—and less severe neuroses—such as hysterical, phobic, obsessive compulsive, and depressive neuroses. The neuroses are not clearly differentiated from “normal” behaviors. Importantly, anxiety—which Freud believed was foundational to human psyche and inextricably linked with societal repression—was portrayed as the underlying condition of all neuroses.

The DSM II also says depressive neurosis could be “due to an internal conflict or to an identifiable event such as the loss of a loved object or cherished possession.” The notion of “internal conflict” is explicitly drawn from Freud’s work, which posited that internal psychological conflicts drive irrational thinking and behaviors.

The third edition of the DSM (pdf), published in 1980, uses language far closer to contemporary professional depictions of mental illness. It does not suggest “internal conflicts” cause depression, anxiety is no longer portrayed as the underlying cause of all mental illnesses, and the manual focuses on creating a checklist of symptoms (whereas, in DSM II, none were listed for depressive neurosis.)

Today, the DSM-5 (pdf) lists various kinds of depressive disorders, such as “depressive disorder due to another medical condition,” “substance/medication-induced depressive disorder,” and “major depressive disorder.” Each of these disorders is distinguished by typical duration and its link to various causes, but the listed symptoms are broadly the same. Or, as the DSM-5 says: “The common feature of all of these disorders is the presence of sad, empty, or irritable mood, accompanied by somatic and cognitive changes that significantly affect the individual’s capacity to function. What differs among them are issues of duration, timing, or presumed etiology.”

The problem is that, though various people could be classed as suffering from a distinct depressive disorder according to their life events, there aren’t clearly defined treatments for each disorder. Patients from all groups are treated with the same drugs, though they are unlikely to be experiencing the same underlying biological condition, despite sharing some symptoms. Currently, a hugely heterogeneous group of people is prescribed the same antidepressants, adding to the difficulty of figuring out who responds best to which treatment.

* * *

Before antidepressants became mainstream, drugs that treated various symptoms of depression were depicted as “tonics which could ease people through the ups and downs of normal, everyday existence,” write Jeffrey Lacasse, a Florida State University professor specializing in psychiatric medications, and Jonathan Leo, a professor of anatomy at Lincoln Memorial University, in a 2007 paper on the history of the chemical imbalance theory.

In the 1950s, Bayer marketed Butisol (a barbiturate) as “the ‘daytime sedative’ for everyday emotional stress”; in the 1970s, Roche advertised Valium (diazepam) as a treatment for the “unremitting buildup of everyday emotional stress resulting in disabling tension.”

Both the narrative and the use of drugs to treat symptoms of depression transformed after Prozac—the brand name for fluoxetine—was released. “Prozac was unique when it came out in terms of side effects compared to the antidepressants available at the time (tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors),” Anthony Rothschild, psychiatry professor at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, writes in an email. “It was the first of the newer antidepressants with less side effects.”

Even the minimum therapeutic dose of commonly prescribed tricyclics like amitriptyline (Elavil) could cause intolerable side effects, says Hyman. “Also these drugs were potentially lethal in overdose, which terrified prescribers.” The market for early antidepressants, as a result, was small.

Prozac changed everything. It was the first major success in the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class of drugs, designed to target serotonin, a neurotransmitter. It was followed by many more SSRIs, which came to dominate the antidepressant market. The variety affords choice, which means that anyone who experiences a problematic side effect from one drug can simply opt for another. (Each antidepressant causes variable and unpredictable side effects in some patients. Deciding which antidepressant to prescribe to which patient has been described as a “flip of a coin.”)

Rothschild notes that all existing antidepressant have similar efficacy. “No drug today is more efficacious that the very first antidepressants such as the tricyclic imipramine,” agrees Hyman. Three decades since Prozac arrived, there are many more antidepressant options, but no improvement in efficacy of treatment.

Meanwhile, as Lacasse and Leo note in a 2005 paper, manufacturers typically marketed these drugs with references to chemical imbalances in the brain. For example, a 2001 television ad for sertraline (another SSRI) said, “While the causes are unknown, depression may be related to an imbalance of natural chemicals between nerve cells in the brain. Prescription Zoloft works to correct this imbalance.”

Another advertisement, this one in 2005, for the drug paroxetine, said, “With continued treatment, Paxil can help restore the balance of serotonin,” a neurotransmitter.

“[T]he serotonin hypothesis is typically presented as a collective scientific belief,” write Lacasse and Leo, though, as they note: “There is not a single peer-reviewed article that can be accurately cited to directly support claims of serotonin deficiency in any mental disorder, while there are many articles that present counterevidence.”

Despite the lack of evidence, the theory has saturated society. In their 2007 paper, Lacasse and Leo point to dozens of articles in mainstream publications that refer to chemical imbalances as the unquestioned cause of depression. One New York Times article on Joseph Schildkraut, the psychiatrist who first put forward the theory in 1965, states that his hypothesis “proved to be right.” When Lacasse and Leo asked the reporter for evidence to support this unfounded claim, they did not get a response. A decade on, there are still dozens of articles published every month in which depression is unquestionably described as the result of a chemical imbalance, and many people explain their own symptoms by referring to the myth.

Meanwhile, 30 years after Prozac was released, rates of depression are higher than ever.

* * *

Hyman responds succinctly when I ask him to discuss the causes of depression: “No one has a clue,” he says.

There’s not “an iota of direct evidence” for the theory that a chemical imbalance causes depression, Hyman adds. Early papers that put forward the chemical imbalance theory did so only tentatively, but, “the world quickly forgot their cautions,” he says.

Depression, according to current studies, has an estimated heritability of around 37%, so genetics and biology certainly play a significant role. Brain activity corresponds with experiences of depression, just as it corresponds with all mental experiences. This, says Horwitz, “has been known for thousands of years.” Beyond that, knowledge is precarious. “Neuroscientists don’t have a good way of separating when brains are functioning normally or abnormally,” says Horwitz.

If depression was a simple matter of adjusting serotonin levels, SSRIs should work immediately, rather than taking weeks to have an effect. Reducing serotonin levels in the brain should create a state of depression, when research has found that this isn’t the case. One drug, tianeptine (a non-SSRI sold under the brand names Stablon and Coaxil across Europe, South America, and Asia, though not the UK or US), has the opposite effect of most antidepressants and decreases levels of serotonin.

This doesn’t mean that antidepressants that affect levels of serotonin definitively don’t work—it simply means that we don’t know if they’re affecting the root cause of depression. A drug’s effect on serotonin could be a relatively inconsequential side effect, rather than the crucial treatment.

History is filled with treatments that work but fundamentally misunderstand the causes of the illness. In the 19th century, for example, miasma theory held that infectious diseases such as cholera were caused by noxious smells contributing “bad air.” To get rid of these smells, cleaning up waste became a priority—which was ultimately beneficial, but because waste feeds the microorganisms that actually transmit infectious disease, rather than because of the smells.

* * *

It’s possible our current medical categorization and inaccurate cultural perception of “depression” is actually causing more and more people to suffer from depression. There are plenty of historical examples of mental health symptoms that shift alongside cultural expectations: Hysteria has declined as women’s agency has increased, for example, while symptoms of anorexia in Hong Kong changed as the region became more aware of western notions of the illness.

At its core, severe depression has likely retained the same symptoms over the centuries. “When it’s severe, whether you read the ancient Greeks, Shakespeare, [Robert] Burton on [The Anatomy of] Melancholy, it looks just like today,” says Hyman. “The condition is the same; it’s part of being human.” John Stuart Mill’s 19th century description of his mental breakdown is eminently familiar to a contemporary reader.

But less severe cases, in the past, may have been chalked up to simply being “justifiably sad,” even by those experiencing them, whereas they’d be considered a health condition today. And so, psychiatry “reframes ordinary distress as mental illness,” says Horwitz. This framework doesn’t simply label sadness depression, but could lead people to experience depressive symptoms where they would have previously been simply unhappy. The impact of this shift is impossible to track: Mental illness is now recognized as a legitimate health issue, and so many more people are comfortable admitting to their symptoms than ever before. How many more people are truly experiencing depression for the first time, versus those who are acknowledging their symptoms once kept secret? “The prevalence is difficult to determine,” acknowledges Hyman.

* * *

Perhaps unraveling the true causes of depression and exactly how antidepressants treat the symptoms would be a less pressing concern if we knew, with confidence, that antidepressants worked well for the majority of patients. Unfortunately, we don’t.

The work of Irving Kirsch, associate director of the Program in Placebo Studies at Harvard Medical School, including several meta-analyses of the trials of all approved antidepressants, makes a compelling case that there’s very little difference between antidepressants and placebos. “They’re slightly more effective than placebo. The difference is so small, it’s not of any clinical importance,” he says. Kirsch advocates non-drug-based treatments for depression. Studies show that while drugs and therapy are similarly effective in the short-term, in the long-term those who don’t take medication seem to do better and have a lower risk of relapse.

Others like Peter Kramer, a professor at Brown University’s medical school, are strongly in favor of leaning on the drugs. Kramer is skeptical about the quality of many studies on alternative therapies for depression; people with debilitating depression are unlikely to sign up for anything that require them to do frequent exercise or therapy, for example, and so are often excluded from studies that eventually purport to show exercise is as effective a treatment as drugs. And, as he writes in an email, antidepressants “are as effective as most treatments doctors rely on, in the middle range overall, about as likely to work as Excedrin” for a headache.

Others are more circumspect. Hyman acknowledges that, when taken in aggregate, all the trials for approved antidepressants show little difference between the drugs and placebo. But that, he says, obscures individual differences in responses to antidepressants. “Some people really respond, some don’t respond at all, and everything in between,” Hyman adds.

There are currently no known biomarkers to definitely show who will respond to what antidepressants. Severely depressed patients who don’t have the energy or interest to go to therapy should certainly be prescribed drugs. For those who are healthy enough to make it to therapy—well, opinions differ. Some psychiatrists believe in a combination of drugs and therapy; some believe antidepressants can be effective for all levels of depression and no therapy is needed; and others believe therapy alone is the best treatment option for all but the most severely depressed. Unfortunately, says Hyman, there’s little evidence on the best treatment plan for each patient.

Clearly, many people respond well to antidepressants. The drugs became so popular in large part because many patients benefited from the treatment and experienced significantly reduced depressive symptoms. Such patients needn’t question why their symptoms have improved or whether they should seek alternative forms of treatment.

On the other hand, the drugs simply do not work for others. Further, there’s evidence to suggest framing depression as a biological disease reduces agency, and makes people feel less capable of overcoming their symptoms. It effectively divorces depression from a sense of self. “It’s not me as a person experiencing depression. It’s my neurochemicals or my brain experiencing depression. It’s a way of othering the experience,” says Horwitz.

It’s nearly impossible to get good data to explain why depression treatments work for some and not others. Psychiatrists largely evaluate the effects of drugs by subjective self-reports; clinical trials usually include only patients that meet a rarefied set of criteria; and it’s hard to know whether those who respond well to therapy benefitted from another, unmeasured factor, such as mood resilience. And when it comes to the subjective experience of mental health, there’s no meaningful difference between what feels like effective treatment and what is effective treatment.

There are also no clear data on whether, when antidepressants work, they actually cause symptoms to fully dissipate long-term. Do antidepressants cure depression, or simply make it more bearable? We don’t know.

* * *

Depression is now a global health epidemic, affecting one in four people worldwide. Treating it as an individual medical disorder, primarily with drugs, and failing to consider the environmental factors that underlie the epidemic—such as isolation and poverty, bereavement, job loss, long-term unemployment, and sexual abuse—is comparable to asking citizens to live in a smog-ridden city and using medication to treat the diseases that result instead of regulating pollution.

Investing in substantive societal changes could help prevent the onset of widespread mental illness; we could attempt to prevent the depressive health epidemic, rather than treating it once it’s already prevalent. The conditions that engender a higher quality of life—safe and affordable housing, counsellors in schools, meaningful employment, strong local communities to combat loneliness—are not necessarily easy or cheap to create. But all would lead to a population that has fewer mental health issues, and would be, ultimately, far more productive for society.

Similarly, though therapy may be a more expensive treatment plan than drugs, evidence suggests that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is at least as effective as antidepressants, and so deserves considerable investment. Much as physical therapy can strengthen the body’s muscles, some patients effectively use CBT to build coping mechanisms and healthy thought habits that prevent further depressive episodes.

In the current context, where psychiatry’s system of diagnosing mental health mimics other medical fields, the role of medicine in treating mental illness is often presented as evidence to skeptics that depression is indeed a real disease. Some might worry that a mental health condition treated partly with therapy, exercise, and societal changes could be seen as less serious or less legitimate. Though this line of thinking reflects a well-meaning attempt to reduce stigma around mental health, it panders to faulty logic. After all, many bodily illnesses are massively affected by lifestyle. “It doesn’t make heart attacks less real that we want to do exercise and see a dietician,” says Hyman.

No illness needs to be entirely dependent on biological malfunctions for it to be considered “real.” Depression is real. The theory that it’s caused by chemical imbalances is false. Three decades since the antidepressants that helped spread this theory arrived on the market, we need to remodel both our understanding and treatment of depression.