Someday, Trump will have a presidential library. Here’s what it might look like.

Washington, DC is more than the city in which the United States’ federal government does its business. It’s a shrine to the nation’s past, a history book of pockmarked granite, limestone, bronze, and marble varieties from a slew of states.

Washington, DC is more than the city in which the United States’ federal government does its business. It’s a shrine to the nation’s past, a history book of pockmarked granite, limestone, bronze, and marble varieties from a slew of states.

Jog the four-and-a-quarter-mile loop around the National Mall and bask in the unrelenting, beautiful intensity of the 555-foot Washington Monument, the tallest structure around, dedicated to the country’s first president. Then there’s the Parthenon-inspired Lincoln Memorial, with Honest Abe ruminating on how best to preserve the Union and play Moses at the same time. Just across the sightly Tidal Basin stands the domed and pillared Jefferson Memorial, minted for the man who wrote the Declaration of Independence. Tucked away beyond some trees nearby is the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, with the cloaked 32nd president, who confronted both the Great Depression and the Axis Powers, looking like the caped crusader he was. And a stone’s throw away in the Potomac River, FDR’s fifth cousin, “the Great Conservationist” Theodore Roosevelt has an 88-acre, woodsy island named after him, home to a 17-foot statue in his likeness, striking the iconic TR pose—his right arm in the air, delivering a frantic, core-gripping speech.

Of course, presidential monuments aren’t relegated to the District of Columbia. Busts of four of the five guys mentioned comprise Mount Rushmore in South Dakota—the other was on site for its unveiling in 1941. And presidential memorials don’t have to come in the form of statues. Presidents John Adams and son John Quincy have a park in Massachusetts named after them. Fourteen commanders-in-chief have presidential libraries and museums dedicated to them, overseen by the US National Archives and Records Administration. Former residences of nearly every president have been preserved and landmarked across the country.

Exceedingly heroic, productive heads of state have garnered the most abundant, awesome tributes. But no matter history’s remembrances of each president—though some have been impeached, others ineffective, and one resigned in disgrace—they all have monuments honoring them. Therefore, a safe presumption can be made that, under virtually any circumstances that may befall the nation over the next three years, one day there will be a ceremony christening a president Donald J. Trump monument. The only debate now is what will it look like and where might it end up?

Matt Worthington, owner of Worthington Monuments based in Fort Worth, Texas, and the vice president of Marketing for the Monument Builders of North America association, says when it comes to building statues and memorials for individuals, “There’s a lot that goes into it.”

“We look into the person,” Worthington continues, “their accomplishments, their ideas, their family, their history, and what’s fitting for the area where the monument will be placed, too.”

In discussing how presidential memorials particularly come about, licensed Washington, DC tour guide Fiona Clem says, “Every time I do research I think, ‘Never underestimate what a bunch of money can do.’”

Shortly after Trump was inaugurated, C-SPAN polled 91 presidential historians to generate a ranking of history’s US presidents, the third such review since 2000. The poll was widely reprinted in the media, in part because it was Barack Obama’s first crack at being listed within it. He slid safely into the 12th slot, but nothing at the top or bottom of the rankings had changed since the initial poll. Abraham Lincoln held on to first place, while his predecessor James Buchanan and successor Andrew Johnson ranked last and second-to-last, respectively.

According to a History.com article about Buchanan’s downtrodden legacy, as president he “took no action to unite a country sharply divided over the issue of slavery and did nothing to stop Southern states from seceding in the lead-up to the Civil War.”

“Buchanan’s cabinet appointees were all rich, southern men,” Clem says, “so he was surrounded by people whose best interest was to keep slavery happening.”

If that wasn’t bad enough, soon after Buchanan’s inauguration, “the Supreme Court infamously ruled in the Dred Scott case that African Americans were not and never could become US citizens, [and] Buchanan allegedly influenced the case’s outcome,” thinking it would put the issue of slavery to rest. However, it only divided the country even more precipitously.

But in Washington, DC, about a ten-block walk from the African American Civil War Museum commemorating the service of black Union soldiers, stands the James Buchanan Memorial. Clem—who wrote a book about Meridian Hill Park, the 12-acre park that surrounds it—describes the Buchanan Memorial as an outlier among local presidential monuments. “The Lincoln, Jefferson, Washington, even the Grant memorial had funding appropriated by congress because of their service to the country,” Clem says. “Buchanan’s monument was a vanity project.”

It was Buchanan’s wealthy niece Harriet Lane Johnston, First Lady to “The Bachelor President,” who provided funding for the memorial in her will. The document also said that Congress had to pass legislation allocating funds toward the building of the statue within 15 years of her death on July 3, 1903. After months of congressional infighting, in which members of the Republican Party characterized the Democrat Buchanan as, among other abysmal adjectives, “weak, timid, stubborn, indecisive, vacillating and disloyal,” the congressional act that put the Buchanan memorial’s construction in motion was passed days short of the deadline on June 27, 1918. It took another 12 years before the monument showed up in Meridian Hill Park.

Clem says she found no evidence of a bill to construct the Buchanan monument even getting proposed in Congress until 13 years after Johnston’s will was first examined. Though a bill eventually passed through the House of Representatives, it did so with 142 congressmen voting against it. “It’s a memorial; usually it’s like who cares?” Clem says, adding, “There’s no way in hell Buchanan would be on the short list of any presidential-monument discussion in Congress, ever, if his niece had not put up the money.”

Johnston also stipulated in her will that the memorial be erected in the nation’s capital, and required that there be an inscription reading: The incorrigible statesman whose walk was always upon the mountain ranges of the law. Clem speculates, thus, that the memorial was always intended to honor Buchanan’s “grand life” in public service—which began in his early twenties and ran through his late sixties—“with less emphasis on his presidency.”

Stephanie Steinhorst, Chief of Interpretation and Education at the Andrew Johnson National Historic Site in Greeneville, Tennessee, says the place of her employment has “a long and complicated history,” though, like the case of the Buchanan Memorial, it was the president’s own descendants—with some help from the local community—that “fought for its legacy as it exists today.”

As president, Johnson is best remembered for being one of just two heads of state to ever be impeached—though, like Bill Clinton, the senate acquitted him. He’s also been denigrated for vetoing a number of bills that would have helped newly freed slaves achieve greater social equality. He’s also famous for appearing to be drunk during Lincoln’s second inauguration.

Though Steinhorst doesn’t wish to be viewed as a Johnson apologist, she observes many facts about the man’s life and circumstances that, upon close examination, could alter traditional perceptions of him. “Johnson’s story is entirely defined by the fact that he inherits his presidency,” Steinhorst says. “A lot of the challenges that he faces, and a lot of the ground work for why his presidency is so troubled is twofold.” First, vice president Johnson was a Democrat who, in 1864, ran with the Republican Lincoln on a ticket designed to reunite and stabilize the country as the Civil War came to an end. Clearly the beloved Lincoln had quite a bit of faith in Johnson, but that didn’t keep Republicans in Johnson’s own cabinet and in Congress from considering him a bit of an enemy. Furthermore, many in the Southern States viewed Johnson as a traitor for siding with the Union even though he was from Tennessee, a state that seceded.

Johnson—who worked his way to the top of the American political mountain after growing up poor and receiving no formal education—had all that working against him. Plus, the “Accidental President” assumed the presidency following Lincoln’s assassination, which occurred just six days after Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered the last of his major armies.

“It’s always hard to follow a martyr,” Steinhorst says. “We spend so much time in our history classes looking at the Civil War and Lincoln, ‘the Great Emancipator,’ but we don’t get to spend a lot of time examining the period that followed.” In observance of Johnson’s unsavory position, Steinhorst says, “It’s such an unprecedented circumstance. How do you restore a country that literally just went through Civil War?” (As he was inaugurated, Johnson himself said, “I feel incompetent to perform duties so important and responsible as those which have been so unexpectedly thrown upon me.”)

In spite of his reputation as a president who, as biographer Annette Gordon-Reed told NPR, viewed the newly freed slaves as “not citizens but serfs, totally under the dominion of white people,” Johnson had emancipated his family’s slaves—some of whom later returned to the estate for paid work—on August 8, 1863. African American communities in Tennessee still celebrate their freedom on that date, and, according to Steinhorst, Johnson donated land and money to freedmen for the construction of churches and schools. Johnson is also the only president who went on to serve as a US senator after vacating the Oval Office, and that whole impeachment thing was over a later-repealed law Johnson argued was unconstitutional. As far as his drinking goes, that might be explained by the turmoil his family continuously experienced. He lost his son in the Civil War, and many in the Johnson family suffered from tuberculosis.

“So, for Johnson,” Steinhorst says, “the big challenge is, how do you put into context where he came from, how he got to the presidency, and the political climate that he was making these decisions in, and then kind of ask yourself, ‘could you have done any differently?’”

For decades after Johnson’s death in 1875, his family continued to live on his homestead before offering it up to the government for preservation. In 1906, president Theodore Roosevelt approved an act of Congress to acquire the adjacent Johnson burial grounds and make it a national cemetery. (Today, there are about 2,000 military veterans buried there.) Franklin Roosevelt then made the homestead—and Johnson’s tailor shop—a national monument in 1942.

“Johnson had 40 solid years of public service,” Steinhorst says. “I think it’s important to try to see these spectrums that all these leaders had to live on, whether it’s today, 150 years ago or farther.”

As my late-August conversation with Steinhorst came to a close, I pointed out to her that Trump, who turned 71 in June, was in his eighth month of public service. “So, we’ll see how it goes,” I said.

“Yes, there’s always time,” Steinhorst replied through some laughter.

In March, the former home of president Trump—where he lived until the age of four—in Queens, New York, was purchased for $2.14 million by an unnamed, Chinese buyer. Misha Haghani of Paramount Realty USA, who represented the property in the auction resulting in the purchase, and Michael X. Tang, a Queens-based lawyer who worked on the deal on behalf of the buyer, both told me that they speculate preservation of the home for future landmark status is something the current owner is likely considering.

* * *

Since 1939, when Franklin Roosevelt donated personal and official papers to the US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) for safe keeping—an action that formally began the Presidential Library system—each subsequent president, along with Herbert Hoover who preceded FDR, has seen a Presidential Library and Museum erected in their name. One of the primary functions of these establishments is to offer educational and research opportunities for those looking to learn more about the presidents. Though according to its website NARA “ensures the facility meets the environmental and security requirements for a presidential archival depository and provides the core professional staff who undertake the archival, museum, programmatic, and administrative operations of the Library,” much of the funding for the memorials arrive via “presidential foundations (private, non-profit support organizations) [that] pay for the core exhibits in each Library’s museum, provide significant funding (and, in many cases, staff) for public programs and education programs.”

This and other facts led to Politico calling the libraries a “scam” and issuing a call for reform in the “broken presidential library system.” “Presidential libraries are perfect examples of just how far presidents will go to control their own legacies,” reporter Anthony Clark wrote in May. “The libraries’ whitewashed exhibits are created by presidential boosters; they host political events; their boards are stacked with loyalists; and many of their important historical records may never see the light of day.”

The NARA website addresses some of these concerns. One question listed in the FAQ section reads: “The Museum parts of the Libraries seem to be favorable to the former Presidents, as they often talk about the positive things the President did while in office. Why is that?”

Their answer notes the exhibits “evolve as the themes transition from contemporary to historical. Examples of more critical interpretations of presidents include the Truman Library’s exhibit on his decision to use the atomic bomb and the Nixon Library’s recently renovated exhibit on Watergate.”

Politico’s reporter was also disturbed by the possibility of nefarious fundraising tactics that could be pursued with a Presidential Library and Museum providing cover. “Someone wishing to gain influence with president Donald Trump could give him a $50 million check today,” Clark wrote, “and as long as they wrote ‘For the Trump Library’ on the memo line, we’d never know about it.”

In an email, James Pritchett, Director of Public and Media Communication for NARA, wrote: “Presidential Libraries are archives and museums, bringing together the documents and artifacts of a President and his administration and presenting them to the public for study and discussion without regard for political considerations or affiliations. Presidential Libraries and Museums, like their holdings, belong to the American people. … When designing museums, NARA works closely with panels of independent historians who evaluate the historical accuracy and balance of each exhibit. We encourage people to visit the Libraries, tour our museums, and make their own determinations.”

Trump has repeatedly admitted to being someone who doesn’t read books to completion, if at all. When asked if there was any reason to think that a Presidential Library and Museum for Donald Trump would not become a thing, Pritchett’s response was, “No.”

* * *

Keith Allen Johnson, a 56-year-old resident of Flowery Branch, Georgia, crafted a sculpture of president Ronald Reagan that stands in the Presidential Library and Museum dedicated to Reagan. Johnson, who describes himself as a rarely found “classical-realistic sculptor,” has been ruminating on a Trump monument for some time. Citing personally conducted research, Johnson says, “I’m the only American sculptor in history who has done seven above-life-size portraits of American presidents, so I have something to say about this.”

In early 2016 Johnson created a bronze bust of Trump, then a GOP candidate, and showed it off to the man during a campaign stop in Atlanta. Johnson said Trump called it “gorgeous,” and added that he’d love to have it in his office.

Since Trump began sitting in the Oval Office, Johnson says he’s painted and sculpted additional portraits of him that today rest in his home studio. Johnson’s vision for a future Trump monument is purposely ostentatious.

“For 30 years Donald Trump has already been creating monuments to himself,” Johnson observes. “He’s created these iconic buildings with his name on them, and he’s in major cities all over the world. You can’t just create a regular monument.”

Instead of drawing the bulk of his inspiration from the likes of the Lincoln Memorial, the Jefferson Memorial, or the presidential libraries and museums, the Boston-born Johnson says his Trump Memorial will take from the New England Aquarium, the Mayflower II exhibit in Plymouth, Massachusetts—a replica of the Pilgrims’ ship—and Walt Disney World’s Space Mountain.

“I may not even be the one who is consulted to be a part of this project,” Johnson concedes, “but I can guarantee that whoever reads this is going to take some of my ideas.”

First, he feels the monument must be in an enclosed building as a nod to Trump’s background in real estate development, but also as a means of protection for the statue centerpiece. “Nobody’s ever going to come in and deface this monument,” Johnson, who anticipates the structure will be privately funded and managed, says. He envisions a three-story, scaled-down version of Midtown Manhattan’s Trump Tower somewhere in Washington, DC that will house a 22-foot sculpture of the 45th president and a museum.

Like the New England Aquarium’s primary exhibit—a 200,000-gallon salt water tank with a spiraling ramp wrapped around it—a continuous rotunda will take visitors from the ground level and circle to the top of the building. There will also be three landings leading to various exhibits that tell not just the story of president Trump, but that of the man, Donald J.

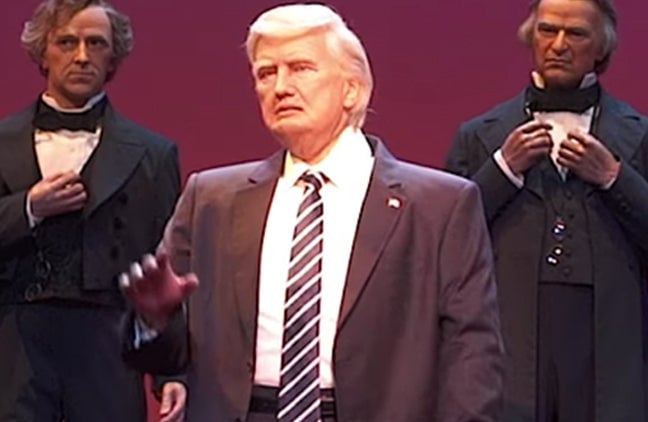

Running alongside the pedestrian pathways, in a callback to the nickname of the president’s campaign, Johnson says guests can take a ride on “the Trump Train,” an actual train the size of a typical family-friendly rollercoaster, making stops on a tour of the memorial. In observance of Trump’s success in television, Johnson envisions a multimedia extravaganza throughout, with replicas of his Trump Tower office, the famous board room from Trump’s reality TV show The Apprentice, and, near the building’s apex, the Oval Office, all teeming with granular detail. “You will literally be transported into these environments with Donald Trump,” he says. Johnson would also like to see wax sculptures of Trump in each setting.

The memorial’s centerpiece will be a solid bronze statue of Trump standing in what Johnson calls a “nationalistic pose,” his right arm extended and holding a flagpole with a massive American flag affixed to it. The flag will appear as though it’s billowing behind him, with the free end of it wrapping around Trump’s left leg. “The glory of America and what America stands for is literally holding this man,” Johnson says.

As the Trump Train tour comes to an end, the cars will dip from the rafters past the statue’s face, and make its final stop at the front of the memorial’s gift shop.

Everything will be America-themed, says Johnson. There will be a Trump Grill with “beautiful food” and two- and three-story jungle gyms for kids to climb on. Johnson estimates a $600-$700 million price tag for his Trump memorial.

* * *

The artist tandem Mary Mihelic and David Gleeson—or, collectively, t.Rutt—have been touring on and off with a mobile Trump monument of sorts for nearly two years. Shortly after Trump made a campaign stop in Iowa, Gleeson purchased a party bus that had been rented by the Trump team. The outside was custom-painted with the block-lettered TRUMP campaign logo, as well as the catchphrase, “Make America Great Again!” Inside, toward the back, past a few rows of plush seats, they found a stripper pole.

But t.Rutt wouldn’t maintain the look of the bus for long, immediately altering it in various ways, generating a multi-ton piece of protest art. First, they added a profound period to make the logo read “T.RUMP,” and they scrawled “Make America Great Again!” in Arabic on it, too. Later, among a slew of other changes, they painted gold-colored teardrops on its side as a nod to the infamous golden-shower story out of Russia about Trump and a couple of prostitutes.

Though they both agree that Keith Allen Johnson’s ideas for his monument are excellent—Mihelic said at one point during a recent phone call, “It’s really hard to find good artists with great, pro-Trump ideas”—the t.Rutt twosome have radically different plans should they ever be asked to construct their own Trump memorial.

Mihelic and Gleeson said they could simply prop their T.RUMP bus on an elevated granite platform somewhere, possibly one that disappears back into the ground, which would allow them to take the vehicle out for a spin, should the inspiration strike. But they also have something separate and a little gorier in mind.

“We’ve toyed around with this crazy idea inspired by the stripper pole on the bus,” Mihelic says. “It would be like a stripper pole/flag pole/totem pole kind of monument,” sticking up through a ground-level bed. “We envision the piece to be approximately 40 feet high in cast bronze with other materials, including aluminum, stainless steel and gold leaf.”

The bottom figure on this totem pole would be a woman crouching down, urinating on the bed—again referencing the Russia story—while propping up a Kim Jong Un, leaning on the pole and giving a salute. A series of skewered Trump victims would people the pole the further one looked up, including figures representing an undocumented immigrant, a Black Lives Matter protestor, a Transgender military officer, a media reporter, an Eskimo, and even some Trump supporters, among others. “Of course there are certain things that we’d put in our monument that his base might be enthusiastic about,” Gleeson says.

Dancing on the pole at intermittent heights, the dead frozen between them, would be Vladimir Putin, Sheriff Joe Arpaio, Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, a shrouded member of the Ku Klux Klan, Trump Senior Advisor and son-in-law Jared Kushner, vice president Mike Pence, and more. Near the pole’s peak, just below an American flag with an ornament of a bald eagle sporting unfortunately tiny wings that disable the bird from flying—a reference to Trump’s below-average-sized mitts—is the president himself, holding on to the pole while doing a traditional Russian dance atop his friends and departed foes.

“It’s kind of like the comedy, absurdist type of thing we do,” Gleeson says of the t.Rutt Trump monument, which Mihelic estimates could cost “several million dollars” to build.

If hard proof emerges that Trump and his campaign colluded with Russian officials, or if Trump turns his administration around and leads America into an era of prosperity rivaling that of president Eisenhower, it won’t determine whether or not our current president gets a monument. (Though the way things are progressing in our strife with North Korea, it’s a wonder if there will be anyone around to erect one.) However, the next handful of years could help us figure out where the memorial will be, what it will look like and what it will say about our 45th president.

Weighing recent and deeper history, the chances of a Trump monument going up in Washington, DC, at this time, don’t look very good. Save for Buchanan, the land in that area is reserved for monuments to better-regarded heads of state. Therefore, the most steadfast of Trump backers—a decade or two or three from now—will likely look to New York City, in Manhattan and perhaps Queens, which is also my home borough, for a Trump memorial resting place. And given Trump’s affinity for hyperbole, along with the funding his offspring and supporters will be able to put toward a monument, the builders of it will likely have no choice but to think bigly.