Democrats and Republicans both have a big blind spot on net neutrality

National Public Radio recently suggested that “tribalism” is the word of the year for 2017. Each day it gains new meaning in US political culture. The latest example is over the case of so-called net neutrality—the principle that internet service providers should treat every bit of data equally, ensuring that users can load any online content they want and at the same speed.

National Public Radio recently suggested that “tribalism” is the word of the year for 2017. Each day it gains new meaning in US political culture. The latest example is over the case of so-called net neutrality—the principle that internet service providers should treat every bit of data equally, ensuring that users can load any online content they want and at the same speed.

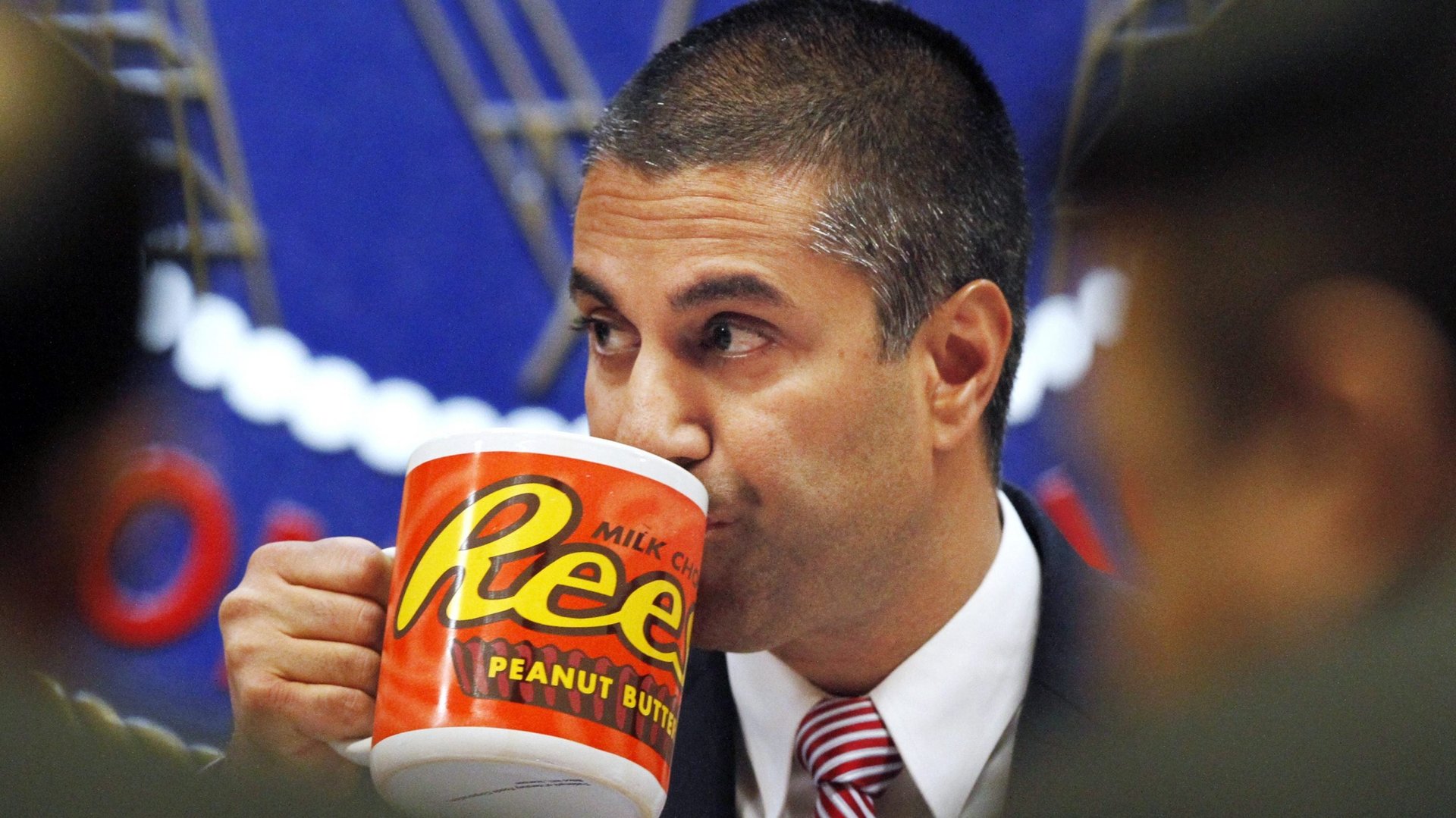

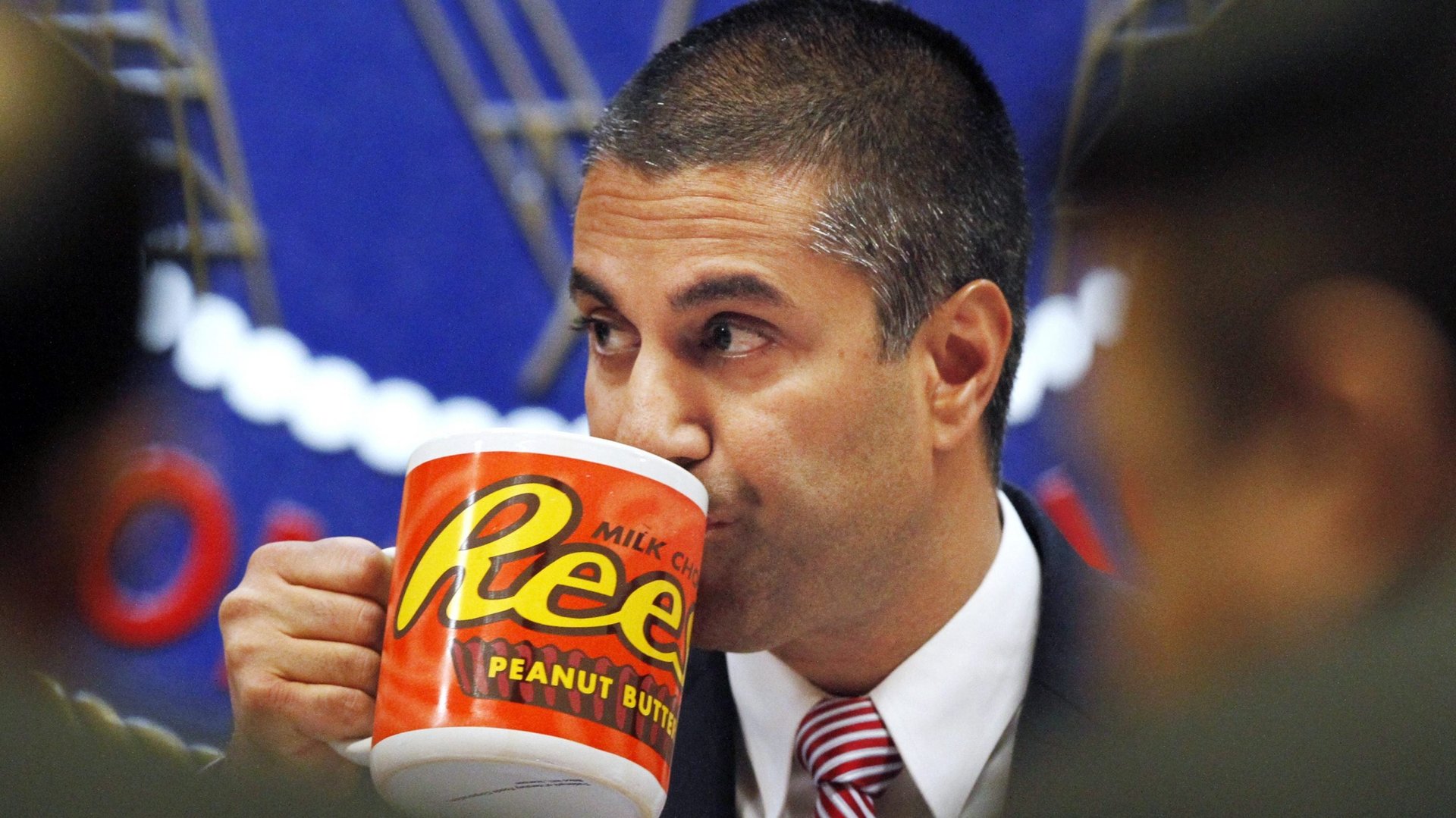

One might think this would be a relatively benign, technocratic issue—especially since a sweeping majority of Americans agree on the equality principle, many quite fervently. But this bit of policy has become tribal, too. The Dec. 14 Federal Communications Commission vote fell along party lines, with Democrats voting to preserve the Obama-era net neutrality rule, and Republicans voting to end it. The tenor of the public debate is similarly polarized, both in the apocalyptic “save the internet” rhetoric of the net-neutrality partisans as well as in FCC chair Ajit Pai’s disregard for the outcry his actions have aroused.

Neither side is talking enough, however, about what really makes net neutrality matter: We have a monopoly problem, and both sides are caught up in it.

The Democratic establishment has followed the path of former president Barack Obama, who mixed with the Silicon Valley elite and whose antitrust monitors exonerated Google while Europe fined the company billions. In general, mainstream Democrats side with the young, shiny, post-industrial platform monopolies—the apps, social networks, and boy-kings of content. These companies have been avid supporters of net neutrality in Washington, surely in part because the principle insulates them from having to pay fees for the 70 percent of internet traffic that goes through their servers. Net neutrality is thus a convenient cause for Democrats to fight for.

Republican leaders, more so than Republican citizens, have chosen instead to hitch their digital future to the behemoth utility companies like AT&T, Comcast, and Verizon. (Pai himself used to work for Verizon.) In March, Republicans in Congress passed a law that allows internet-service providers to monetize users’ data, as Facebook and Google already do. Maybe the grayer Republicans prefer this older generation of companies, which deem strong net neutrality an intolerable burden to their business models. But it is hard to have much sympathy for a business model in which 129 million people in the United States have no choice of broadband provider.

Tribal allegiances come with blindspots. Republicans leaders have allowed themselves to ignore the fact that the telecoms they’re supporting are some of the country’s most hated companies. On the other side, when TV personality and net-neutrality crusader John Oliver rails against corporate monopolies, he conveniently neglects to mention Facebook or Google.

To see what a post-net-neutrality world might look like, actually, one need look no further than Facebook. In poorer regions of the world, where people’s internet access options are limited, it offers programs like Facebook Zero and Free Basics, which provide cost-free access to select parts of the internet—hand-picked by the company. When customers lack choice or oversight, a monopoly can edit the internet in its own image.

One person who has expressed concern about the corporate influence of Google and Facebook is Breitbart chairman and former Trump advisor Steve Bannon. He reportedly believes the companies should be regulated like utilities, and when Breitbart reported on the new Republican proposal for a telecom-friendly, net-neutrality-lite law, Bannon’s reporter offered gleeful hints that the feds would be coming after Facebook, Google, and Twitter next.

These loyalties do waver. Senator Elizabeth Warren has spoken about Google’s monopoly threat, and the Trump administration is challenging the AT&T-Time Warner merger. But on basic matters of internet policy, both political tribes have tied themselves to monopolies, and if those ties hold, we all stand to lose.

That said, not all monopoly threats are created equal. The platform companies like Facebook and Google have vast wealth and vast troves of our personal data, but it is still possible to opt not to use them and use one of their fledgling competitors instead. The danger from telecoms is more immediate, if only because so many people have no real choice over where their service comes from—especially rural and low-income customers.

Federal protections like net neutrality are thus necessary, if not a panacea. Without net neutrality, we’re likely to see the rise of codependent monopolies—imagine AT&T charging Google millions of dollars to reach viewers of its YouTube platform, for instance, while Google learns to enjoy how the arrangement keeps out new, smaller competitors.

What else should we do to protect the internet from monopolies? Europe’s emerging personal-data protections are an essential check on abuses of market power. Next, it’s time to rearm antitrust enforcement for the internet economy; old laws made for railroads and robber barons are far more relevant than regulators have realized.

All the while, we need alternatives to the big internet-service providers. Rural, often conservative areas have demonstrated the promise of deploying broadband through cooperatives, owned and governed by their customers, just as co-ops brought electricity to farmers almost a century ago. Cities and other local governments have set up publicly owned networks, too. Both strategies often result in higher speeds at lower costs than the big telecoms offer. These community networks are designed to serve their members, not extract profits for investors. Smart policy can ensure that the telecoms of the future are more nimble, more local, and more accountable than what we have now.

The same can be done for platforms. “Zebra” startups and “platform co-ops” are aiming to create online businesses that seek to benefit their communities, rather than enriching investors by seeking scale above all else.

The internet was in danger well before Pai took aim at net neutrality—and that danger comes from monopolies. His crusade is a symptom of the problem, but not the cause.