Housing prices rose in 69 out of 70 of China’s biggest cities. That’s pretty scary

One of the ongoing debates about China’s economy is whether the country faces a housing bubble. Data out today suggest that government attempts to rein in the market haven’t done much. In 10 of China’s 70 biggest cities, July prices for new, non-commodity commercial housing rose more than 10% from the previous year.

One of the ongoing debates about China’s economy is whether the country faces a housing bubble. Data out today suggest that government attempts to rein in the market haven’t done much. In 10 of China’s 70 biggest cities, July prices for new, non-commodity commercial housing rose more than 10% from the previous year.

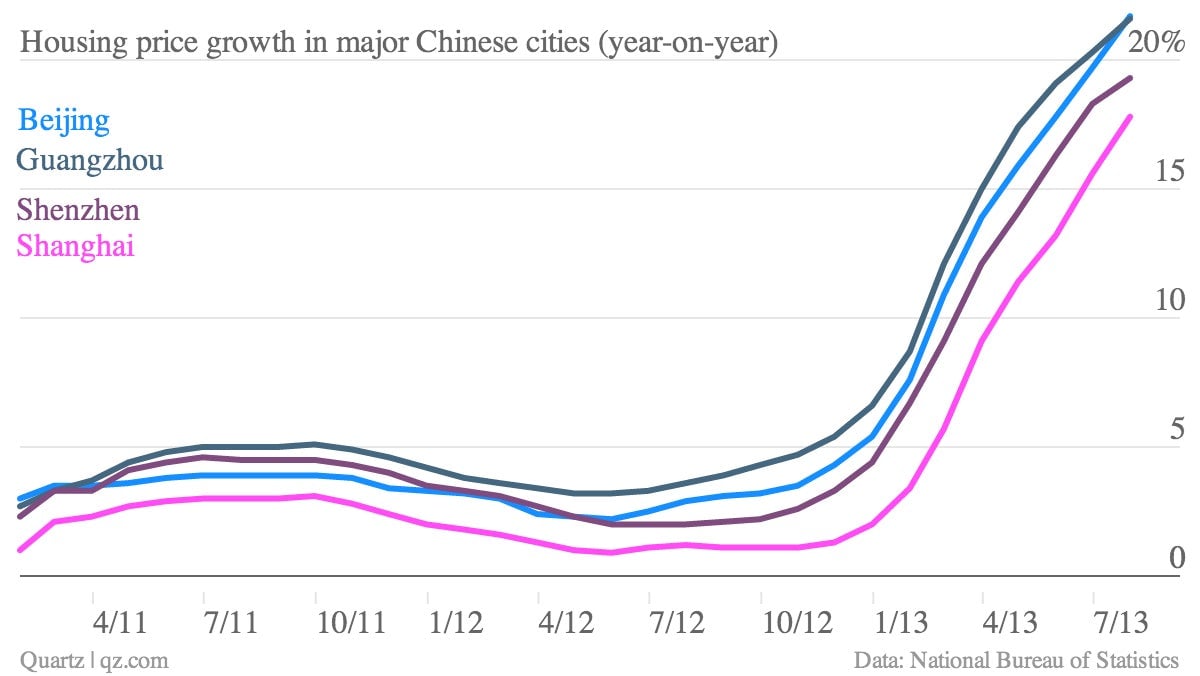

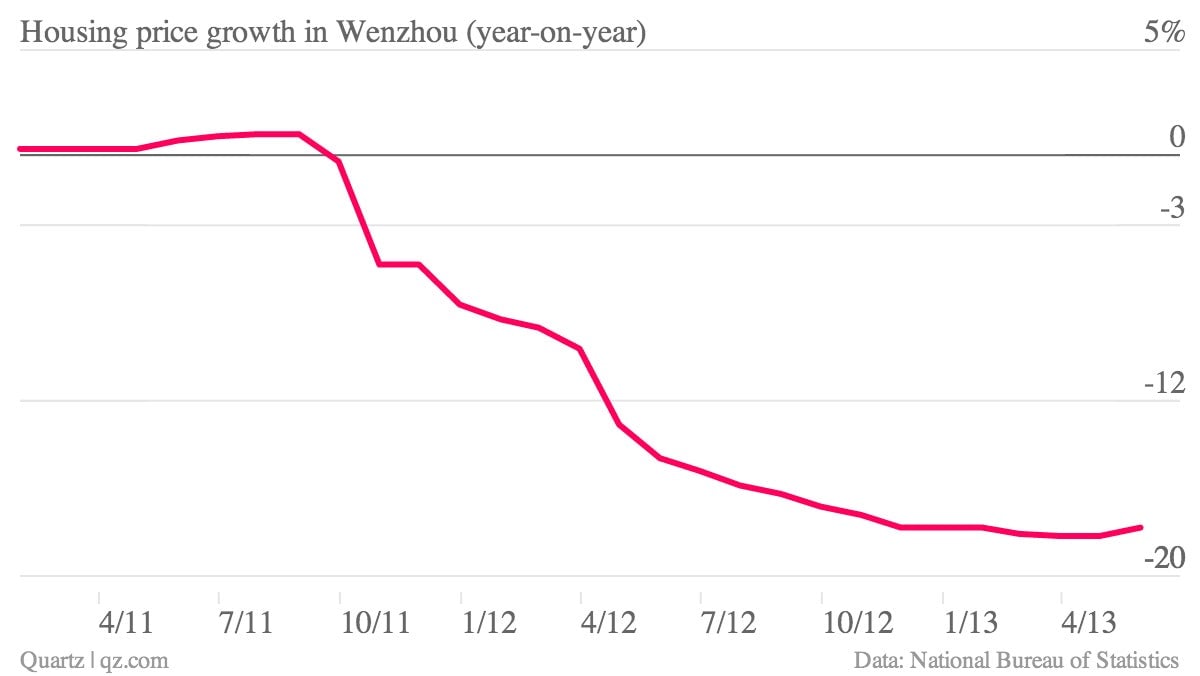

The greatest growth was in Beijing, where prices surged 18.3%, and Guangzhou, where they leapt 17.4%. Shenzhen and Shanghai came in close behind with price increases of 17.0% and 16.5%, respectively. But prices were overheating pretty much across the board: In 69 out of 70 cities, prices rose to some degree. Only in Wenzhou, where a shadow banking crisis triggered a housing market collapse in 2011, did prices decline compared with July 2012.

This is important because it highlights that the dilemma the government faces when it comes to real estate prices is intensifying.

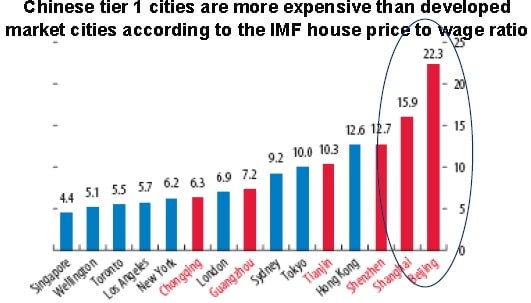

First, there’s the paradox of why, despite widespread dissatisfaction with rising prices, people keep shelling out. Due to the closed capital system, Chinese people who lack either strong government connections or an export/import business—i.e. most people—aren’t allowed to invest outside the country. Government-rigged deposit rates offer little or sometimes negative return on savings.

That leaves them with two main investment choices: Chinese stocks or property. Yet stock market returns are generally awful, as well as risky, as you can see from the last couple of “fat finger” episodes. That makes housing far and away the most attractive thing to invest in. Along with social pressures to own property before marriage, that’s helped keep both speculative and genuine demand steady, even as it becomes less and less affordable.

And the consistent growth in speculative demand masks what many suspect to be a market with ample supply, which implies that current prices are much too high.

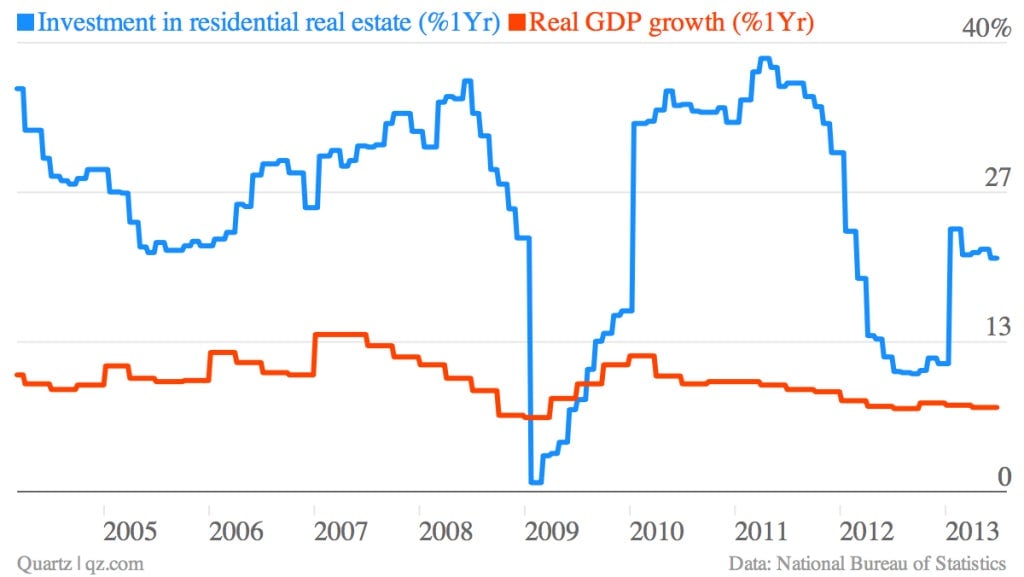

Given that real estate investment drives a hefty portion of China’s GDP, using policy measures to keep the lid on prices threatens hobbling a key driver of economic growth. Data out earlier today show that dozens of local governments invested heavily in property and infrastructure in the first half of 2013, hinting how reliant they are on that type of spending to generate growth, even though it’s taking more and more money to achieve that:

But keeping China’s real estate boom going inflames China’s financial system risks. That’s not in the way that most assume; unlike how the US housing market plugged into the 2008 financial crisis, Chinese households have relatively little mortgage debt. However, property is often used as collateral on bank loans. A panic that prompts lenders to start collecting on and selling off collateral would cause prices to plummet. The case of Wenzhou offers a disquieting example of easily this might happen.

More worrisome still, though, is that the higher prices go, the more savings Chinese households have to have tied up in real estate—and the more a sharp decline in prices would be devastating for Chinese households. And that will defer the long-awaited shift to consumption-led growth even longer.