Why it’s so hard to fill some jobs even when everyone’s looking for work

Skills for America’s Future, a policy initiative run out of the Aspen Institute, was created in 2010 as a spin-off of President Obama’s Jobs Council and was originally led by longtime Obama supporter Penny Pritzker. With Pritzker now installed as the new Commerce secretary, Aspen announced earlier this week that the skills-training program will continue with executives from Snap-On and Gap at the helm.

Skills for America’s Future, a policy initiative run out of the Aspen Institute, was created in 2010 as a spin-off of President Obama’s Jobs Council and was originally led by longtime Obama supporter Penny Pritzker. With Pritzker now installed as the new Commerce secretary, Aspen announced earlier this week that the skills-training program will continue with executives from Snap-On and Gap at the helm.

In the wake of that news, National Journal talked with René Bryce-Laporte, the outgoing program manager for Skills for America’s Future, about the challenges of training workers in an economy where employees can expect to develop new skills consistently throughout their careers—even if they have the increasingly rare experience of staying in the same field or even with the same company. Bryce-Laporte has spent more than 15 years working in policy and advocacy around the issues of providing social and economic opportunity to low- and middle-income Americans. Edited excerpts of the conversation follow.

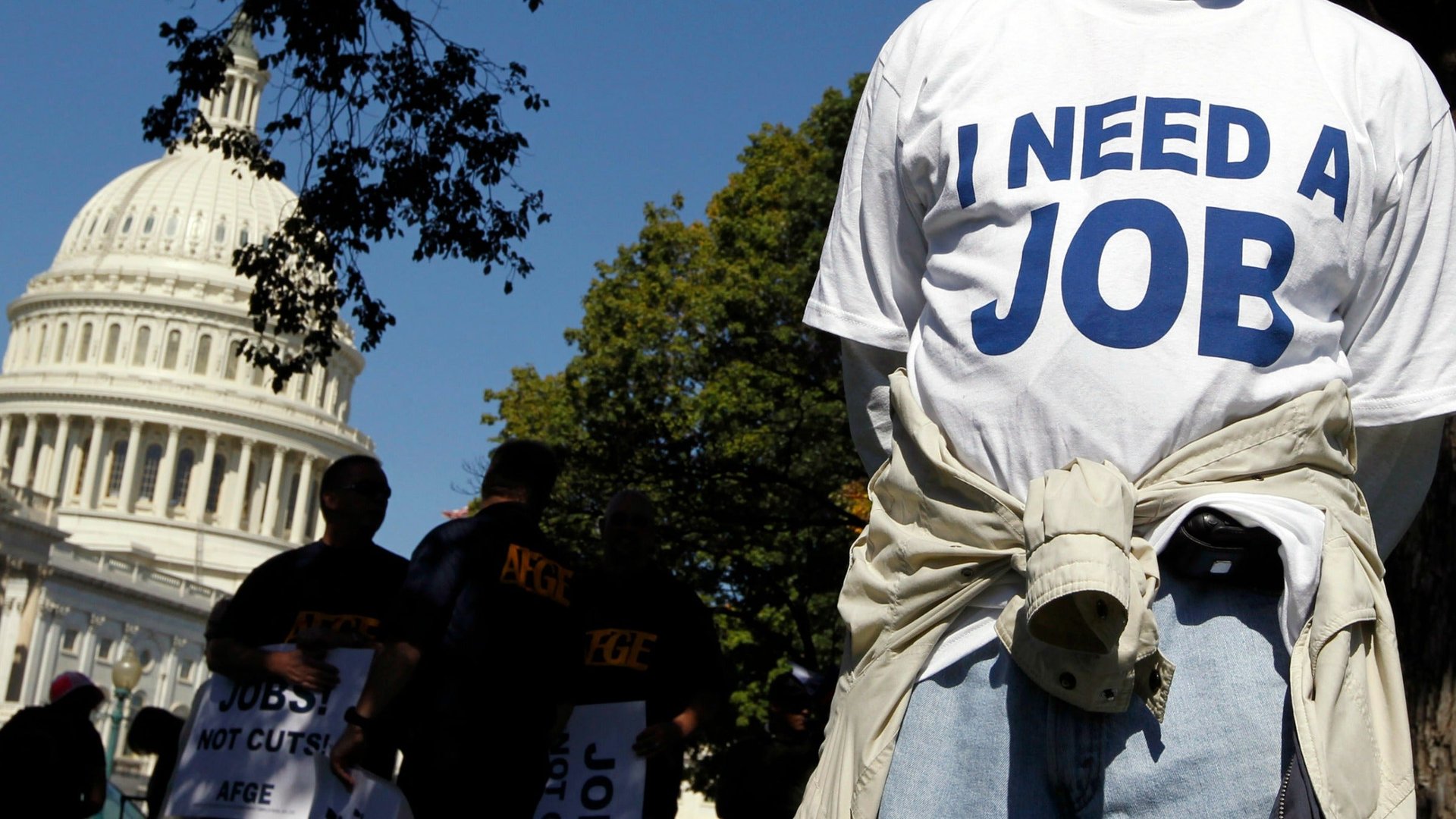

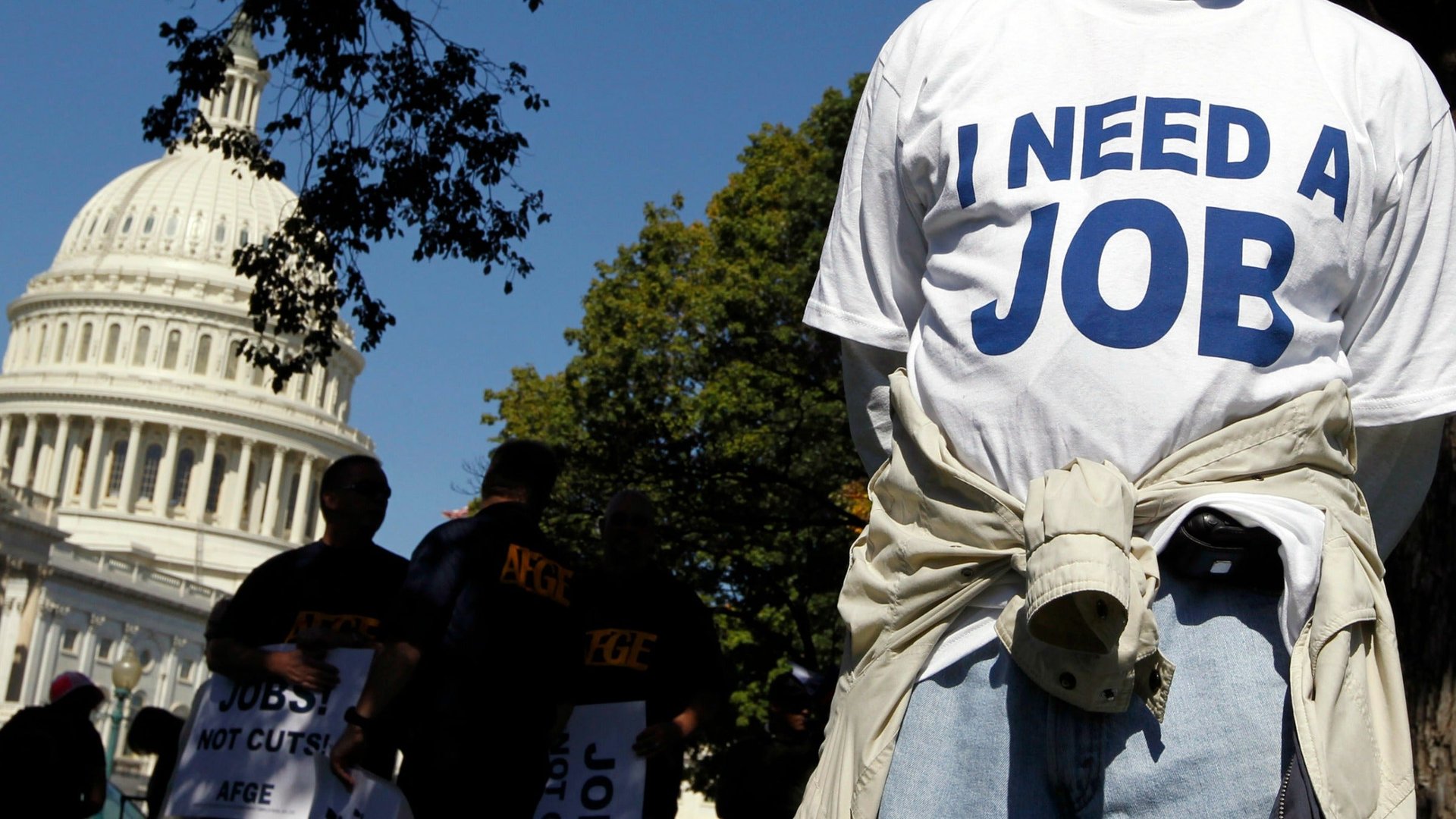

The U.S. has an unemployment rate over 7 percent, yet as we’ve been traveling around the country, we constantly hear from employers that they can’t fill positions, particularly those that require higher skills. How is that possible?

One of the reasons Skills for America’s Future was started was that the Jobs Council kept hearing from employers concerned that they had jobs remaining open because they couldn’t find workers with the skills they needed. The idea was to create an initiative to work with community colleges, and to promote partnerships between them and businesses to match education and training to employment opportunities.

The precise number of jobs that remain unfilled is elusive, but we know that the number is high. Now, jobs sometimes go unfilled because of natural fluctuation in the workplace—somebody leaves a job and it stays open for a few months. There are some observers who say that the idea of a skills gap is overstated, that vacancies persist because employers can’t find people with the skills they need at the rate they’re willing to pay. But it is true that employers complain they have a hard time finding workers with the skills they need. About 40 years ago, only one in four jobs required more than a high school education, but now about two in three jobs require more training. And workers now really need to think of learning as a lifelong task. That’s a huge shift from the days when you did one job that never changed for one employer and then you retired.

Working in a factory requires a different kind of skill than it used to—the same is true in agriculture, even. I serve on a board in Arkansas, and we went to a town in the Delta that has a farm that used to have a couple hundred people working in the field. Now it employs two people, operating all the machines.

I’ve seen some surveys with employers who talk about problems finding workers with traditional workplace skills—showing up to work on time, having basic literacy, needing workers who can problem-solve. That’s not new technology in play—some employers have always complained about these skills being absent.

It’s interesting that you mention those basic skills, because it’s definitely not what we think of when we hear “job training.”

Yeah, those are some of the job-readiness skills that some people still overlook. There are employers who now work with community colleges to develop certificates that help show that a worker is ready. The National Career Readiness Certificate basically tests those kinds of skills I was talking about—can they read for information, locate information, do math? The standardized test is administrated by the testing service ACT and evaluates a student’s preparedness for the workplace. Bison Gear, a manufacturer in Illinois, makes sure all of its employees have passed the NCRC as a requirement of employment.

So when we talk about more training or education, it doesn’t necessarily mean getting more people through four-year colleges.

That’s right. Not every kid has to be ready to go to Harvard or Columbia or Michigan. More training could mean a professional training school. Or community colleges, which are great places to go to get a degree or specialized skills that are of value to an employer.

The average district tuition and fees for community colleges is $3,130 per year while state school tuition and fees are now $8,660 each year. So the cost is not nothing, but it’s much more affordable, and particularly if you’re targeting certifications. Almost half of community college students receive financial aid. And there are employers who will subsidize the cost of school for workers.

One of the challenges of skills training is the fluidity with which people change jobs and careers these days. It’s not just a matter of getting training one time and then being set for a lifelong career.

Even if you stay in the same basic field your whole life, things are going to change. A smart employer is going to figure out how employees can develop and adapt to meet those changes. Sometimes that can be done onsite with the company. Many employers—though not enough of them—are partnering with post-secondary schools to help build a workforce with the skills that they need, even setting up specific classes. Sometimes that’s to train new workers, but often it’s targeted to existing employees.

For instance, Des Moines Area Community College has partnerships with John Deere and Accumold, both of which work frequently with the school to set up classes so that workers can acquire x, y, or z skill. Snap-On Tools works with Gateway Technical College in Wisconsin, which has a whole center to train workers for jobs. They even fly the Snap-On flag on campus.

The energy industry is one sector that aggressively working to train new workers to replace their aging workforce. Nearly 40 percent of energy workers will be eligible to retire within the next five years. Part of the challenge is due to slower hiring, some of it is likely due to a weaker economy. But it is also related to the challenges of finding workers with the skills they need.

PG&E in California is working with more than 30 community colleges to train the next energy workforce. Interestingly, while many of their graduates work for PG&E at the end of the training program, a decent number end up working for other companies.

Are there other sectors particularly at risk?

Manufacturing, of course. The National Association of Manufacturers says they have about 600,000 jobs that are open because employers can’t find workers with the skills that they need. Companies have been working to get folks to understand that the manufacturing floor does not look like it did in your granddaddy’s time. It’s not nearly as loud as you’d think, very clean. And it requires workers with a high level of skill.

Similarly, the IT industry reports problems finding workers to fill jobs. Some employers are pushing to fill those through immigration. But others are coming at this in a different way. The RITE Board in northeast Ohio is looking to cultivate an IT workforce that can supply local employers. Northeast Ohio would not be confused with Silicon Valley in any way, and these are not IT companies. But every company has IT needs and they don’t want to always go out of state—or sometimes out of the country—to fill those. So they’ve built a curricula and a whole training program to produce a cadre of qualified students who will be ready to come work for them after graduation.

Are there other ways companies can partner with learning institutions to develop the workforce they want and need?

Partnerships can take many forms. We’ve talked a lot about curricula, and making sure schools can teach towards the needs of employers. Some employers are also providing equipment that students can practice on. Often you have employees working with really expensive equipment and you want to know they can operate it carefully.

Mentorships can be helpful, as well. A couple years back, a partnership between New York Public School, the City of New York, and IBM launched P-Tech, a grades 9-14 school.

9 through 14?

It covers high school and then takes students through earning an associate’s degree. They’re doing a lot of what I’ve been talking about: providing training that goes on in school, mentors in the form of IBM employees who can provide guidance to students and families along the way, and then upon graduation, students get the first bite at jobs at IBM.

Mayor Rahm Emanuel liked the idea so much, he pushed for it in Chicago. They’ve launched several schools along the same model, and IBM is talking to people in other states, as well as working with New York to spread the idea across the state. IBM has provided a playbook that others can look at and adapt to their community. Not every place is going to have a big employer like IBM that can be the hub. But the idea is the same—guiding students through their training with some mentorship.

Amy Sullivan is a director at the Next Economy Project.