An Alcatraz prisoner on the special hell of New Year’s Eve

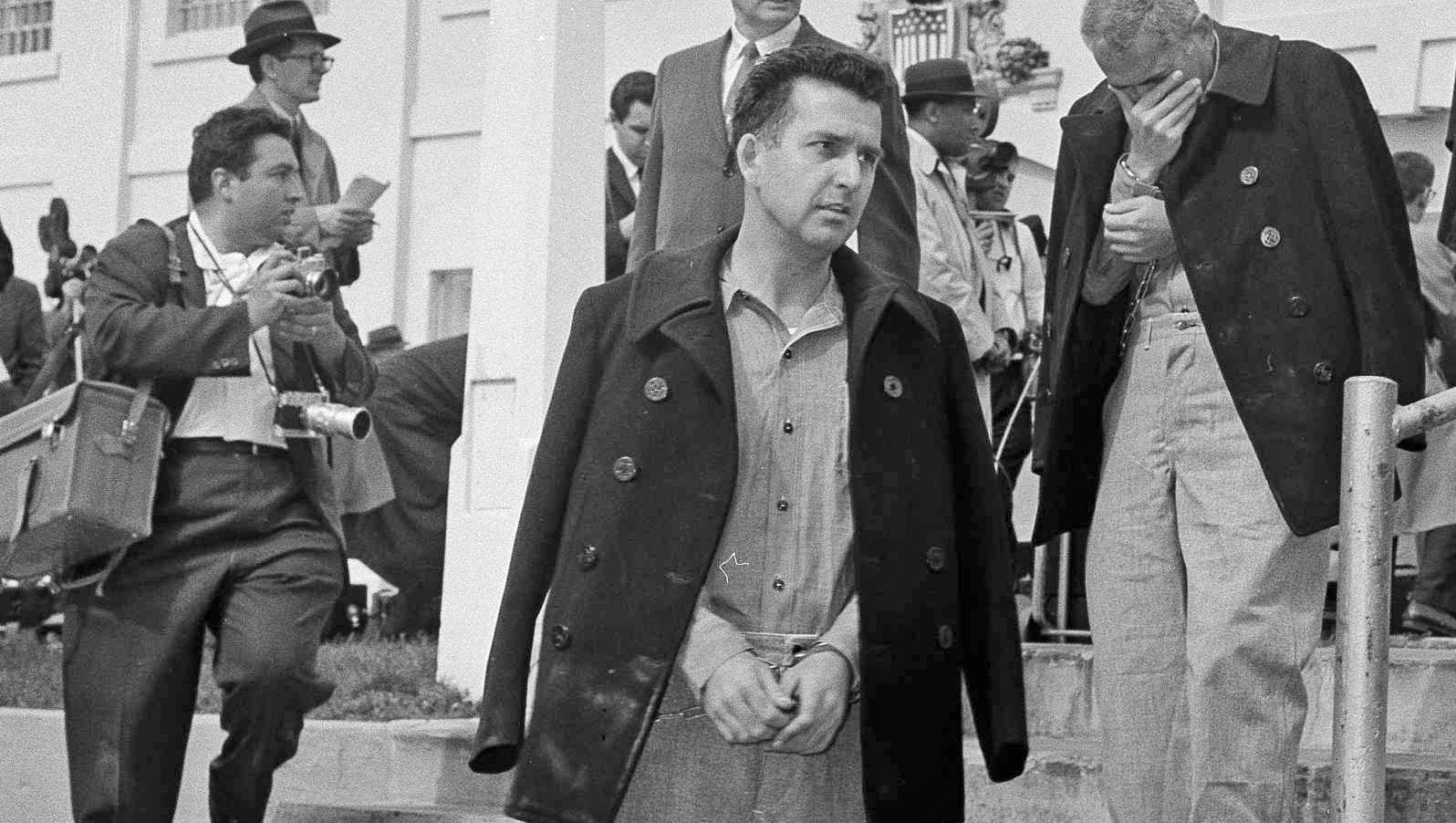

Party boats cruise by San Francisco’s Alcatraz Island year-round, including on New Year’s Eve. But New Year’s Day is one of few when tourists can’t set foot there.

Party boats cruise by San Francisco’s Alcatraz Island year-round, including on New Year’s Eve. But New Year’s Day is one of few when tourists can’t set foot there.

That seems only right. Today, Alcatraz is a national park visited by more than a million people a year. But for its inmates—around 250 men at a time, for almost three decades—the skyline always loomed as a tantalizing reminder of their proximity to the city. And marking each new year was an especially awful exercise.

“The yacht club, which was directly across from the island, would always have a big New Year’s party,” Jim Quillen, inmate 586, says in narration recorded for today’s touring visitors. “If the wind was blowing from that direction to the Rock, you could actually hear people laughing, you could hear music, you could hear girls laughing. You know, you could hear all the sounds coming from the free world, at the Rock. And New Year’s was always the night we heard it.”

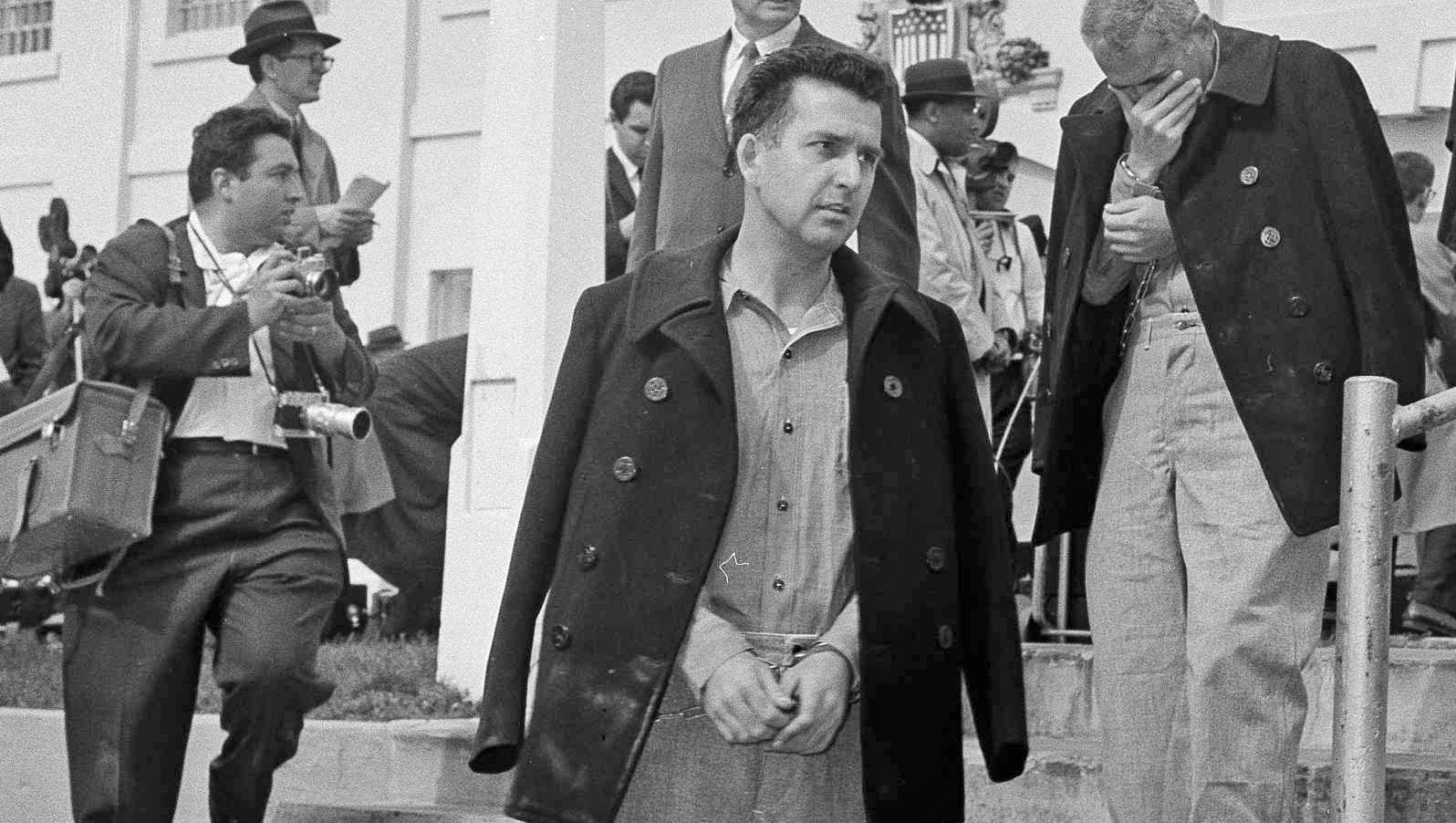

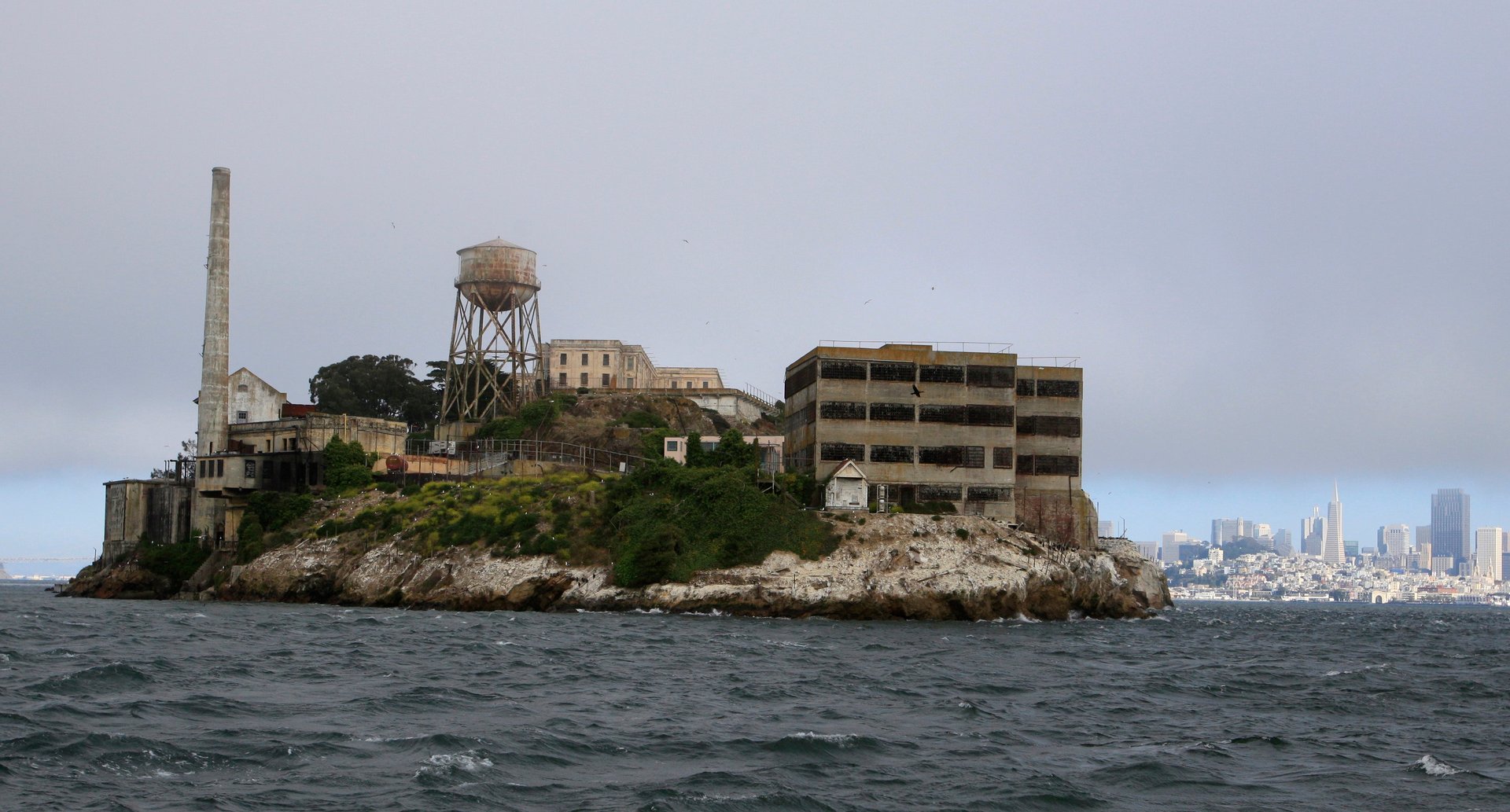

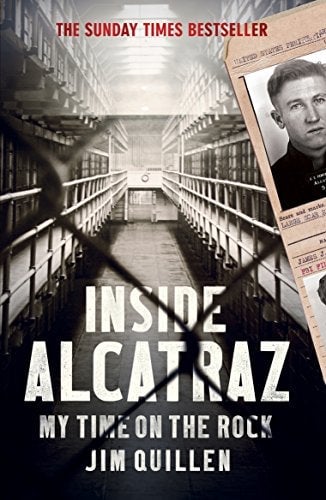

Quillen’s 1991 autobiography documents his criminal activity, hell-raising, and eventual redemption. Recaptured after breaking out of the California state prison at San Quentin, he arrived at Alcatraz in 1942 “after a wild crime spree of robbery and kidnapping,” as true-crime writer Jason Lucky Morrow put it. Quillen would remain at Alcatraz for a decade.

“There was never a day you didn’t see what the hell you were losing, and what you were missing, you know,” he says in the tour audio. “It was all there for you to see. There’s life. There’s everything I want in my life, and it’s there. It’s a mile or a mile and half away. And yet I can’t get to it.”

From 1934 to 1963, Alcatraz was home to killers, kidnappers, bank robbers, and the like. All were deemed too dangerous to live free, and many—including Quillen—were too untamed to do their time peaceably. Prison can break people physically and psychologically, and Alcatraz was good at doing both.

Quillen, who died in 1998, found a new life as a husband and a father after a second term at San Quentin, David Ward writes in Alcatraz: The Gangster Years. He retired as a radiology technician. President Jimmy Carter granted Quillen a federal pardon in 1980—eight days before New Year’s Eve.