Why is China creating utopian “art cities” in its former wastelands?

The Chinese mega-city Shenzhen normally conjures images of wide streets, tall buildings, booming factory production, record-breaking construction speed, money, pollution, and materialism. But on the eastern edge of the city, 15,000 Chinese people—many of them artists—don loose linen and cotton clothes, live on narrow lanes and alleys in traditional-style houses, and go against all stereotypes about modern Chinese living. “It’s like a Hollywood film set of an old Chinese village,” says Mary Ann O’Donnell, an American who has lived in and researched Shenzhen for over 20 years. Even down to the lattes.

The Chinese mega-city Shenzhen normally conjures images of wide streets, tall buildings, booming factory production, record-breaking construction speed, money, pollution, and materialism. But on the eastern edge of the city, 15,000 Chinese people—many of them artists—don loose linen and cotton clothes, live on narrow lanes and alleys in traditional-style houses, and go against all stereotypes about modern Chinese living. “It’s like a Hollywood film set of an old Chinese village,” says Mary Ann O’Donnell, an American who has lived in and researched Shenzhen for over 20 years. Even down to the lattes.

This is Wutong Art Village. Nestled into the foothills of a stream-lined mountain where plants overflow into lantern-lit courtyards, it’s a creative refuge where local strawberries sit on sun-drenched wooden tables and freshly baked cakes are sold out of wagons on the side of the road. Comprised of eight urban villages in Wutong Mountain Scenic Area in Shenzhen’s Luohu District, Wutong Art Village is an artistic, atmospheric, miniature world.

Here, the traditional Chinese instrument guqin is more popular than club music. Spirituality is small talk. People often ask each other if they “have beliefs” or explore religion in some way, against the secular mainstream. Artists and spiritual seekers favor a slower pace, a do-it-yourself alternative lifestyle, and take part in activities like calligraphy (shufa), meditation, and vegan dining. It’s not odd to see a string of Tibetan prayer flags connecting a hotel with Buddhism-inspired decor to a shop selling enzymes, goji berries, and essential oils. Scrolling through a Wutong resident’s WeChat makes it feel like a lifestyle brand made of funky wooden tea tables and generosity.

“Wutong is a special place,” says Hu Yongjian, an art writer and abstract photographer who lives in the city. “When you cross the bridge you enter a different world. When we’re in the city we forget Wutong—because it is Shenzhen’s utopia (wutuobang).”

So how did Wutong come to be—and in China’s richest city, nonetheless? Representing Shenzhen’s experimental ethos and opposing its speed, Wutong’s fate will be determined by its ability to balance the old and new visions of China—or to create a beautiful one of its own.

Wutong Art Village: an exception to the rule

Wutong is the exception to Shenzhen—which began as the exception to China.

The village sits on the outskirts of Shenzhen, in the country’s south. Shenzhen was the first place where people could xiahai (jump into the sea of private markets) and experiment with capitalism during the reform years of the 1980s, after Mao’s life and economic policies came to an end. As China’s first special economic zone, it gave tax benefits and preferential treatment to foreign investment and grew at an alarming rate. Shenzhen is now known for its capitalist affect and “Shenzhen speed,” a phrase coined after the record-breaking construction of the Guo Mao building in 1985. However, this catchy moniker veils its true meaning: exploitation. Labor was not suddenly performed faster—rather, more of it was performed in a shorter amount of time.

Shenzhen is a city of experimentation; the epicenter of DIY and innovation. Some even call it China’s Silicon Valley. Wutong is an iteration of that innovation, but in which the handmade is privileged over the quickly made.

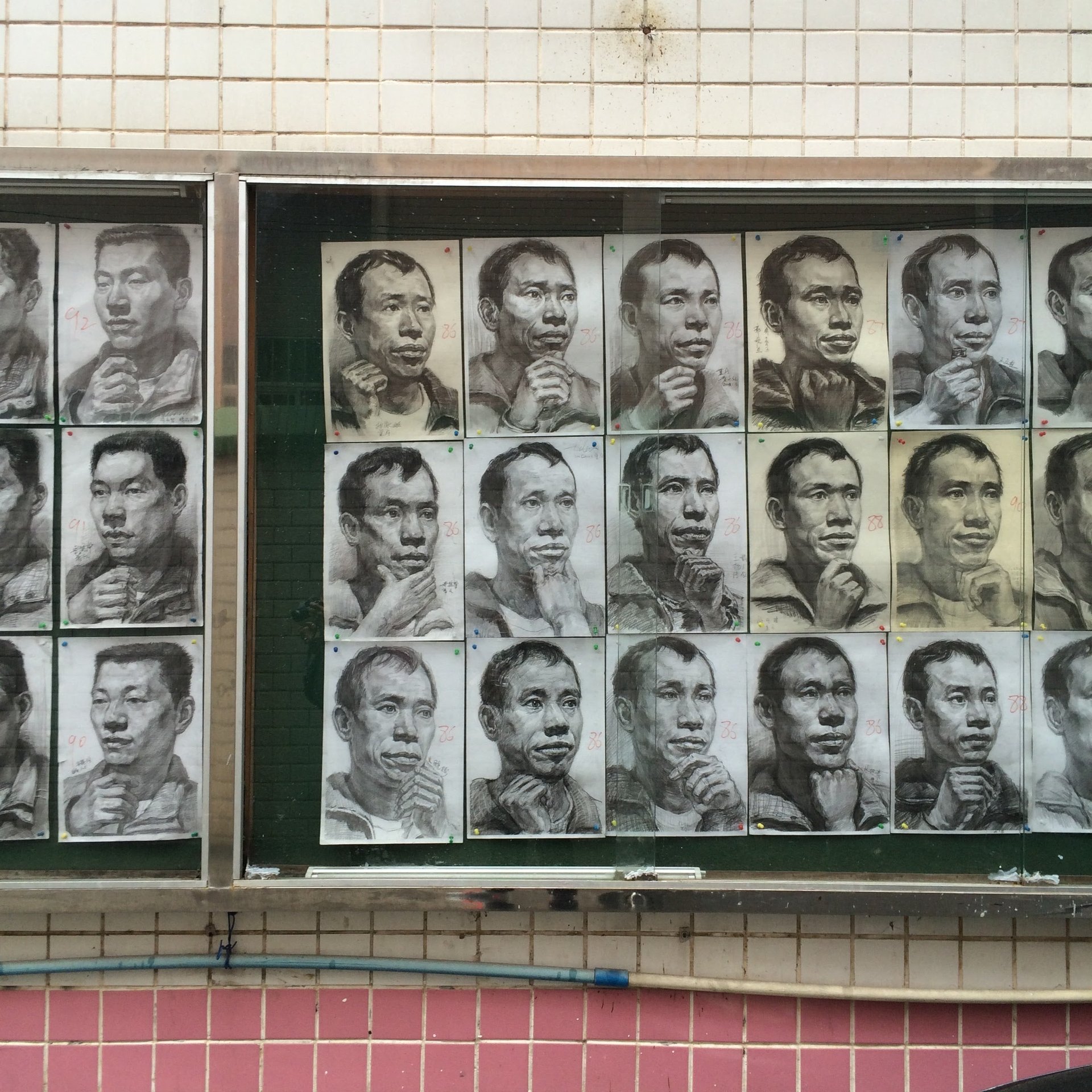

Unlike Dafen Oil Painting Village down the road, whose booming industry was born out of copying Western art, the art being made in Wutong is not from other places but from other times. Gazing at the canvases that line artists’ studios (and up and down the village streets themselves), it’s like looking at a real or imagined Chinese past, long before Mao Zedong or Deng Xiaoping. People in Wutong mix Taoist, Buddhist, and Confucian forms of thought. National arts academies, which are schools where children learn the ancient classics rather than the math, science, and Chinese that dominate the mainstream modern education curriculum, are in every village. In fact, the media called Wutong dujincun, or “Reading Classics” Village (link in Chinese).

Aside from the art, Wutong’s main attraction is its mountain, Wutong shan. Dainty white bridges join the villages over the stream that comes down from the mountain’s waterfall. However, creatives and their studios are largely invisible to weekend hikers. Hidden from the public, artists enjoy quiet and relatively cheap rent. The mountain and water, two critical elements in Chinese art, philosophy, and mysticism, help Wutong thrive, not only because they protect the land from urban development, but also because they attract artists and spiritual practitioners seeking silence and proximity to nature.

Zhao Yi, a 49-year-old northern Chinese man who goes by John, came to Wutong in 2008 with several health problems. He was looking to get away from the city life that he says made him sick. He works freelance (ziyou, which literally means freedom), as many in Wutong do, teaching English and Chinese, helping friends, hiking the mountain, and pursuing his newfound interests: meditation and chanting. “Here you can be free,” John says. “The mountain gives you all the energy you need.”

It’s part of a broader trend—the comeback of “the hermit”—which promotes the stillness of monk-ish mountain living. Others describe the mountain and its foothills as a place to live a free life—a treatment, or zhiliao. It’s a place to go when you want to recuperate from overwork, illness, or heartbreak; a location where you can leave the world and explore a new way of living that’s slow and scattered with art—utopic, even.

And who wouldn’t want a studio in utopia?

Wutong

’

s artist community

Shen Zhoulai’s studio is in a converted factory in Kengbei Village, one of the eight villages that comprise the Wutong Art Village. Shen is a 30-year-old man from Guangdong’s northern neighbor, the Jiangxi province, who has striking cheekbones and lanky limbs. He moved here nine years ago for the cheap rent and quiet environment. “At the beginning it was like the interior [which is generally less populated and economically developed than the coast] and the countryside…There weren’t a lot of artists here,” Shen says.

Western music blares from large speakers. His CD collection includes Tracy Chapman, Sinead O’Conner, and John Lennon. Shen’s 3-year-old daughter plays for our attention as her mother comes in and out of the room, which is filled with paintings and sculptures. We peel through stacks of paintings of a figure—“always me,” he says—and of horses, dark themes, and a sense of drowning.

Shen likes to keep to himself, rarely leaving his studio. Many artists here lead lives reminiscent of the hermit artists of traditional China, who went into the mountains to paint landscapes called shanshui, which means mountain-water. Others in Wutong borrow from past forms of Chinese culture in a more social way, debating religious and philosophical concepts to better themselves and discover life’s purpose beyond material gain. They gather at Awaker Bar, a spiritual-programming space, whenever a master of Taoist thought, Waldorf education, or the Enneagram passes through town.

While some artists don’t care for Wutong’s spiritual dabblers, Long Shuo, a ceramicist, finds peace equally in both, chipping away at a Buddha sculpture and then meditating in an adjacent room. For Long, there was no other place like Wutong—somewhere “fresh” where he would be both artistically and spiritually inspired, in good company meditating, and producing ceramics with other Jingdezhen artists. (“What’s the connection between Buddhism and Taoism, and art?” I once asked him. “They are both paths of the heart,” he replied.)

This is in direct contrast to Dafen Oil Painting Village, the aforementioned Western-copying art village the next town over. “Dafen is business and Wutong is art,” a young singer told me one night in the garden of a local restaurant. Dafen painters produce copies of European paintings en masse and ship them around the world—even to Wal-Mart. Many artists in Wutong used to live and work in Dafen, but when they felt it had gotten too commercial, they decided to move to Wutong, which is a more peaceful environment planned for the production of original art.

Moving to Wutong is part of a trend of art and creative-industry development across Shenzhen. One of these developments, 93 Art Park, resembles other similar sites in the area: Neon flower sculptures fill the concrete space between formerly industrial buildings, artists rent studios, and kids play on colorful swings. Xingtong, the director of the complex, aims to provide these artists with studios and a sales platform. She came to Shenzhen because it is the best place to “do a little thing,” as many locals say. In other words: to invest in new business. I’d often see Xingtong standing across the street from 93, looking at it like an artist gazes at her canvas, calculating her next move. The project, like much of Wutong, is an unfinished work, an individual’s dream.

Many of those individuals wish to keep China’s traditional culture alive. “We have to bring culture back,” says Deng Chunru, the leader of nearby Niuhu Art Village. Deng, a member of the family that has governed the village for generations, handpicks artists to live in Niuhu. All the artists Deng recruits are men, which reflects the Chinese contemporary art world where women are often outnumbered. By doing so, he has created a small but focused contemporary art scene with a very different culture to the other art villages that surround it. “I had this idea, and in Shenzhen you can make ideas into reality.”

Rather than merely copying Western modernization models or participating in the global market like Dafen artists, Wutong and Niuhu are fusing tradition with the future. Liu Lang, a young musician from Shandong Province, came to Wutong in 2016 to set up a place devoted to guqin, the traditional Chinese instrument that is popular in Wutong. He took over an art villa, hanging paintings and filling the room with guqins for people to learn, play, and listen to. “There’s a responsibility to spread guqin culture, so I came,” Liu says. “Whether the government had asked me to come or not, I would have come.”

Liu’s aspirations are in line with China’s broader national agenda: to make China cultural again.

China’s soft power

In recent years, Beijing has declared a push for soft power. In a departure from merely wielding their might in large-scale industrial production and political force, soft power is a way to gain influence through culture and values. Still, art is not for art’s sake, as Chairman Mao once forbid. Soft power aims to make China prominent in the public eye and attractive as a nation—though sometimes it can be lucrative too, such as the recent Hong Kong-Hollywood collaboration, The Great Wall.

The art village designations are part of this effort. They’re a branding strategy to draw domestic tourism and encourage the consumption of art objects, leisure goods, and coffee. These sites are intended as areas for cultural production and consumption and are sometimes also places where artists live full time. Unused warehouse spaces, abandoned after decades of iron and steel production, are converted into artist studios, and the designation sometimes involves the building of structures like museums, art villas, and theaters to mark the space as a site of creative industry. But the government may not stick around to fill those spaces with programs or exhibitions. In the wake, people can come in and make these designations their own, carving out little spaces for creativity.

The government designated Wutong as a creative-industry site for the production of original art in 2011, using the fact that artists were already moving to this place for cheap rent, fresh air, and inspiration as a starting point to do their part in the national soft-power agenda. Besides the factory buildings, two types of housing predominate, where people often both live and create art. The first are “old houses,” as residents call homes that predate the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution, when much of China’s traditional architecture was destroyed. These are single-story buildings with iconic upturned roofs, tiny ceiling windows, and gray exteriors. The second are “handshakes,” which are newer pastel three- and four-story buildings named because they are built so close together that neighbors can shake hands out their windows.

While this creative haven may seem too good to be true—both inside and outside of China’s growth- and productivity-driven regime—there’s another reason unrelated to art and industry it can exist: The government doesn’t protect the artists because they are making money—it’s because their haven for creativity is environmentally protected.

Saving the environment

Wutong sits atop the Shenzhen Reservoir, Hong Kong’s precious and under-resourced water source. Following the last half century’s uneven history of water-resource management in China, in 1989 the area was labeled an ecological preservation site and national forest. While usually economic success is the only thing that can protect an area against demolition in China, the ecological zoning provided a loophole to this formula. Building new structures is illegal here, so factory spaces and pre-Cultural Revolution houses are repurposed to create art studios and cafes.

Since artists were already living in the area, it was also a natural place for an art village. Not all ecological preservation sites are art villages, but Wutong’s mountain and water make it an especially inviting atmosphere for creative types. It’s therefore a perfect soft-power project: Artists can create an artistic atmosphere, and traditional Chinese culture can be mined for contemporary resonance, even if money can’t be made.

Against the less fortunate backdrop of the demolition of many of Shenzhen’s urban villages, Wutong Art Village survives. Not all art villages have the same fate however: The history of art villages in Beijing is one of eviction, commercialization, or worse.

China

’

s history of art villages

Moving to the outskirts or suburbs of a city is common practice for artists in China. The Chinese art village as it exists today goes back to the 1990s when international activist and art star Ai Weiwei and his contemporaries returned to China from New York. Inspired by New York’s East Village, they began squatting in the ruins of the Old Summer Palace (Yuanming yuan) in Beijing. Once evicted from there, they moved into the old factory buildings northeast of the city center in the industrial-cum-art district now known as 798.

Another village in Beijing, Caochangdi, is known for being Ai Weiwei’s home. A quieter maze of gray brick buildings, Caochangdi is tucked back from the main road and is home to other famous artists like Wu Wenguang and Zhuanghui, as well as international galleries. Artists who couldn’t afford to live or work 798 or Caochangdi moved to Black Bridge, only to be evicted when the village was demolished in summer 2017 (link in Chinese).

Still further out from the city center, Songzhuang is home to a fringe artist community, and its film festival causes controversy every year due to its subjection to state censorship. Songzhuang also faces demolition as the state builds government housing nearby, as does Guangzhou’s Redtory. The former can-factory-turned-art-district will soon be turned into a financial district, though the blueprints include preservation of one small strip of the art village (mostly because the developer happens to like art).

While many art villages are being demolished, Wutong looks like it will be spared because of environmental reasons. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t gentrifying to meet China’s changing needs.

Tradition vs. innovation

Chen Heng Chao is a single mom and Wutong newcomer who moved from Dafen in 2015. She runs Kindred Spirits Art Gallery, one of a few galleries in the area. We chat one night over homemade wine in the gallery, which is currently exhibiting garments made using old designs and natural dyeing methods, as well as Chen’s own oil paintings of peaches. At Kindred Spirits, Chen holds parties to cultivate the art scene. She considers the gallery a space for social practice, where she can gather many women—which is unusual for the Chinese art world—around art, Chinese culture, and beauty.

Earlier that day, a wealthy Beijing art collector had visited her and commented on the mess and smell of trash in Wutong’s little streets. Chen felt embarrassed. She felt caught between wanting to modernize Wutong into the sparkling city the collector was expecting, and her contentedness to enjoy her pet project and freedom to explore in this old style village.

Ruffled, we walked down the street to have tea with Xu Gengliang, who has lived in Wutong since 2009, about improving the conditions. Xu’s studio is filled with unique ceramic pieces, Buddha figures set into frames like paintings, and handmade tea cups, which are scattered throughout the whimsical, well-lit space. The two talk about how they could get citizens to clean up rather than get the government to step in. Xu has been in Wutong long enough to know that if something needs to get done, a citizen-led effort was a surer bet than government support.

The conversation meanders to the topic of the art industry in the village, and eventually they conclude that Wutong artists should open their studio doors and keep consistent gallery hours in line with traditional art institutes. Though Wutong can pride itself on its traditional practices, it’s ultimately still a village on the outskirts of Shenzhen, and therefore will always be influenced by its wake.

Wutong is an art village: a place to heal, an environmental preserve, and a place to revive traditional Chinese culture. But to allow it to be all these things, it needs to take part in the nation’s wider narrative. Artists in Wutong can continue creating for creation’s sake, but to keep their art village alive, they need to play into China’s greater soft-power goals: to display a visible art market to woo domestic attraction, and maybe even make some money.

Still, creativity finds fertile grounds here. From the businesses in highrises to the urban villages, from the swelling city sprawl to the lush landscapes seen from the sides of traffic-blocked highways, it provides a respite from the vision of China the rest of the world presumes. If you want to escape it, all you need to do is head past the orchid farms, across the bridge, and over the river to Wutong Art Village.