After India and Indonesia, Malaysia could be next in investors’ line of fire

As with its Asian peers India and Indonesia, foreign investment in Malaysia has been hard hit by the mass exodus of money from emerging markets. Its softening currency, swelling national debt and narrowing trade balance make Southeast Asia’s third largest economy a prime target for jittery investors.

As with its Asian peers India and Indonesia, foreign investment in Malaysia has been hard hit by the mass exodus of money from emerging markets. Its softening currency, swelling national debt and narrowing trade balance make Southeast Asia’s third largest economy a prime target for jittery investors.

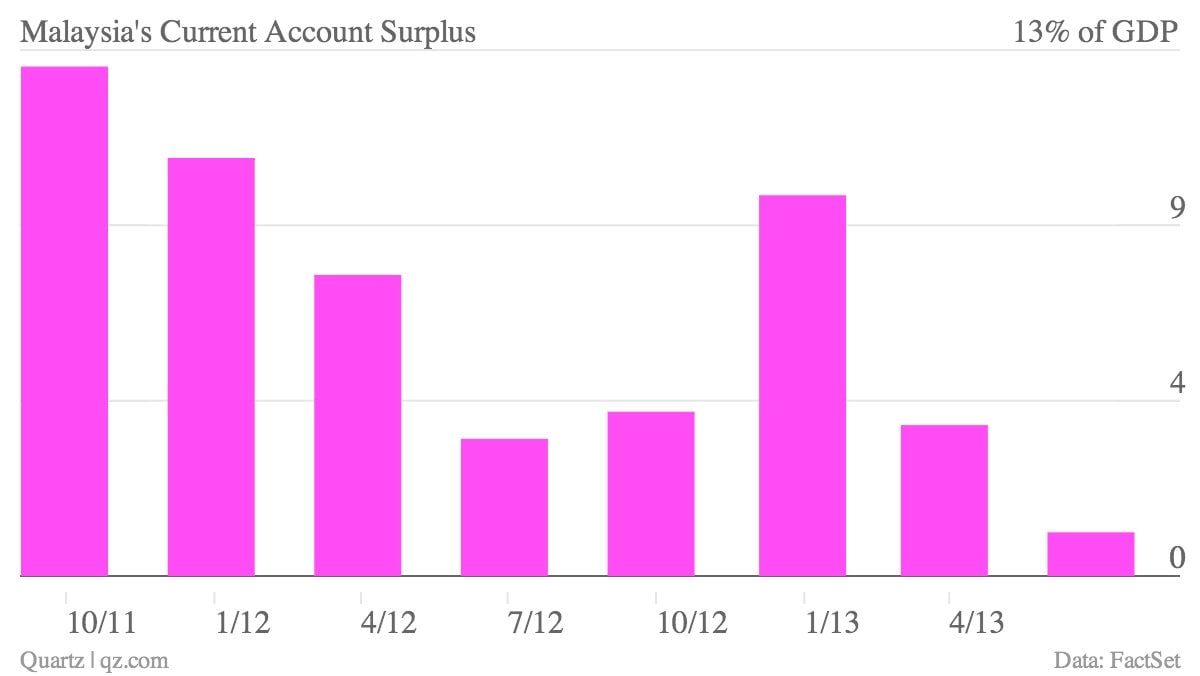

Exports outpaced imports by just 2.6 billion ringgit ($790 million) in the second quarter, creating the country’s smallest current account surplus since early 1999. The deteriorating trade balance will intensify the pressure on the ringgit, which has already fallen to a 3-year low against the US dollar. Meanwhile, the economy expanded at a slower-than-expected rate of 4.3% last quarter from a year earlier, and the central bank said GDP growth would be 5% at best for the full year, down from its earlier forecast of 5-6% growth.

What’s behind Malaysia’s woes? Falling commodity prices and weakening demand from China. But what makes the country particularly vulnerable to international investor sentiment is the fact that investors hold nearly 50% of its bonds (paywall), much higher than 30% on average for emerging markets. Its worsening trade balance has scared foreign investors more, leading them to dump 6.6 billion ringgit ($2.04 billion) of Malaysian government bonds in June, the country’s largest-ever outflow in a single month.

The government’s balance sheet gives investors more reasons to fret. Its debt as a percentage of GDP, 53%, is among the highest in Southeast Asia. Ratings agency Moody’s warned last week about Malaysia’s dwindling revenues and relatively high government deficits. Late last month, Fitch Ratings cut Malaysia’s outlook to negative from stable, citing rising debt levels and a lack of budget reforms.

The government relies heavily on petroleum for cash, which made up 33.7% of federal revenues in 2012. Malaysia spent 24 billion ringgit ($7.2 billion) last year on fuel subsidies for consumers and industries, a burden that’s “not sustainable,” according to Abdul Wahid Omar, who heads up economic planning for the prime minister. Omar said the government will soon unveil reforms to cut deficits and reduce subsidies to address rating agency concerns.

But here’s the problem: Cutting fuel subsidies, tightening the money supply, and staggering out big investments in sectors like aviation and real estate will all hurt growth. The task is even harder considering the country’s political predicament. Malaysia’s ruling coalition won elections in May with its slimmest-ever majority. That could strip prime minister Najib Razak of the political might to push through meaningful reform.