Men think they’re better off working alone, even when it’s not the case

One of the puzzles of the persistent gender wage gap is why women are highly overrepresented in certain fields, like the nonprofit sector, and hugely underrepresented in other fields, like financial institutions and executive positions in major companies. One reasonable question to ask about the gap is: How much should we blame “the system” (i.e.: clubby nepotism, sexism, lack of paternity leave) and how much should we chalk this up to women’s decisions (i.e.: leaning out in their late 20s and choosing careers that pay less even when they had options to earn more)?

One of the puzzles of the persistent gender wage gap is why women are highly overrepresented in certain fields, like the nonprofit sector, and hugely underrepresented in other fields, like financial institutions and executive positions in major companies. One reasonable question to ask about the gap is: How much should we blame “the system” (i.e.: clubby nepotism, sexism, lack of paternity leave) and how much should we chalk this up to women’s decisions (i.e.: leaning out in their late 20s and choosing careers that pay less even when they had options to earn more)?

Peter J. Kuhn and Marie-Claire Villeval wade into this contentious field with a new study: ”Are Women More Attracted to Cooperation Than Men?” The short answer is, well, yes. The more complex answer is: Yes, because men demonstrate more overconfidence in their own abilities and distrust in their colleagues’ aptitude, except under key situations.

Numerous studies have shown that women prefer to work in teams, men prefer to work alone, and women perform worse in competitive environments, even when their performance was similar to men in noncompetitive environments. Kuhn and Villeval wanted to understand why. Although their experiment is highly theoretical, its real-world applications are clear. Women outnumber men in many helping occupations, from charitable organizations to nursing, both of which offer cooperative production with less financial reward.

Their most important conclusion involves perceptions of relative competence. Basically, if you think your colleagues are idiots, you don’t want to cast your lot with them. But if you think your colleagues are smart, you’ll see the advantages in working as a team. Women demonstrated less confidence about their own abilities, the researchers said, and more confidence in their potential partners’ abilities. They were also much more sensitive to increasing their potential partner’s incomes, reinforcing a well-established idea that women demonstrate more “inequity aversion” than men. That is, they’re less comfortable with their colleagues making dramatically different salaries.

But, interestingly, the researchers found that a tiny tweak in team-based compensation erased this entire gender gap.

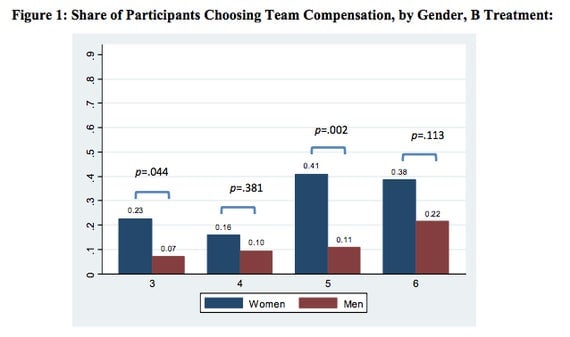

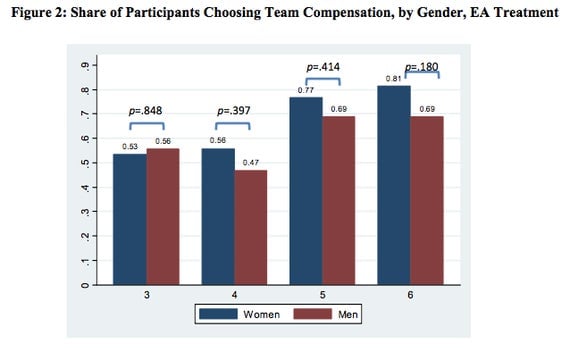

Kuhn and Villeval cleverly ran an experiment allowing men and women to select team-work versus solo-work, and then re-ran the experiment increasing the returns from excellent team-work by about 10%. Once they did this, the cooperation gap between men and women disappeared, as you can see in the difference between Figure 1 and Figure 2 below (EA Treatment = efficiency advantages, or modestly increasing the gains from teamwork).

“The gender gap in the willingness to form a team vanishes when efficiency advantages are introduced,” the researchers said, “because both genders increase their team choices, but men’s increase is much larger. ” In other words, men are more sensitive than women to small tweaks in team-based compensation.

Maybe that sounds absurdly theoretical to you. But it’s a lesson many corporations are already putting to work. The number of Fortune 1,000 companies using workgroup or team incentives for at least a fifth of their workers more than doubled between 1990 and 2002, and management have switched to team-pay in both the minimill and the apparel industry.

This isn’t just a story about gender wage gaps; it’s a story about motivation. In manufacturing and other complex processes, teamwork is vital. It’s not enough to focus on making brilliant women feel confident. It’s also key to make overconfident men trust that their colleagues just might be competent.

Derek Thompson is a senior editor at The Atlantic, where he oversees business coverage for TheAtlantic.com.