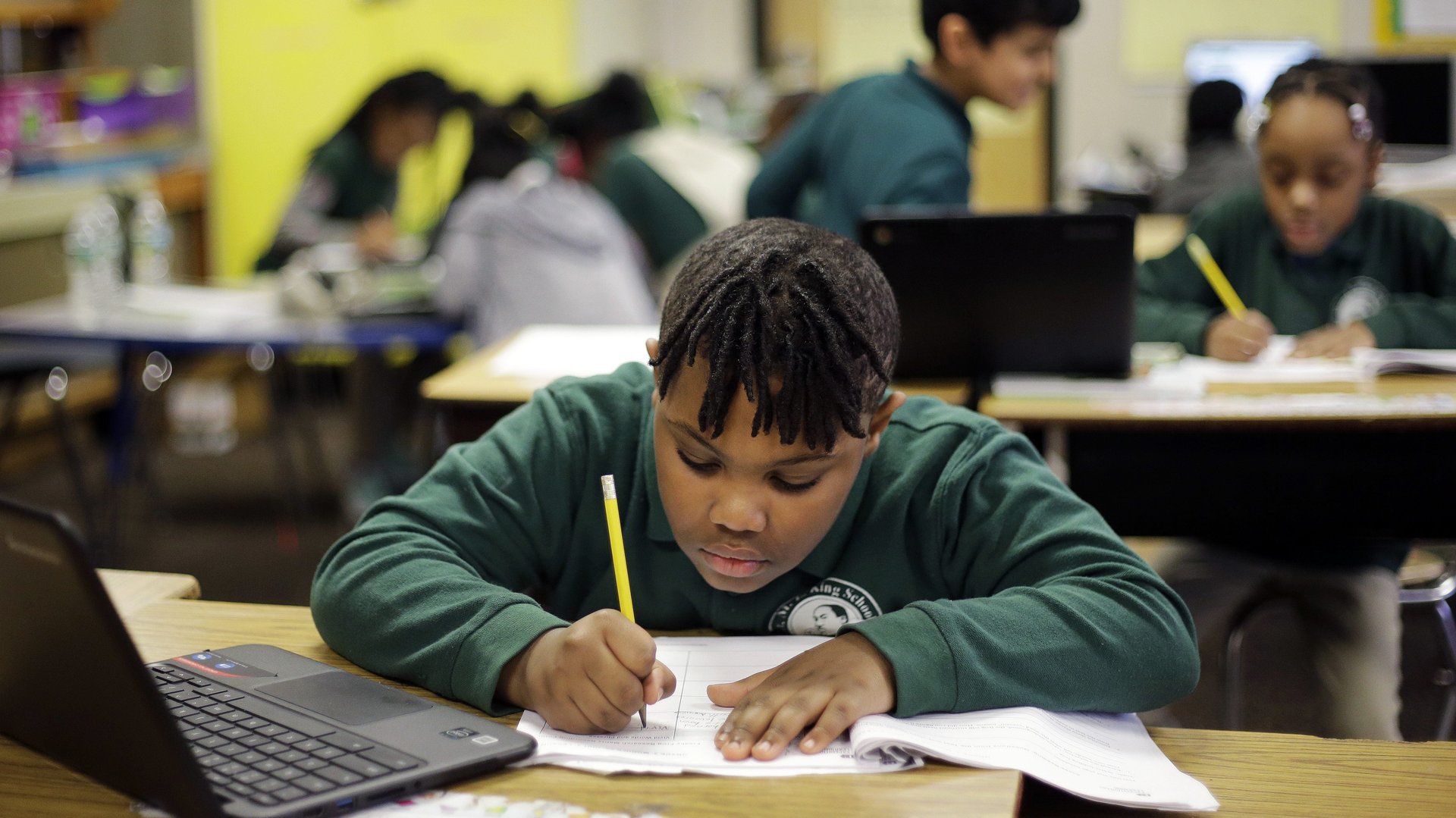

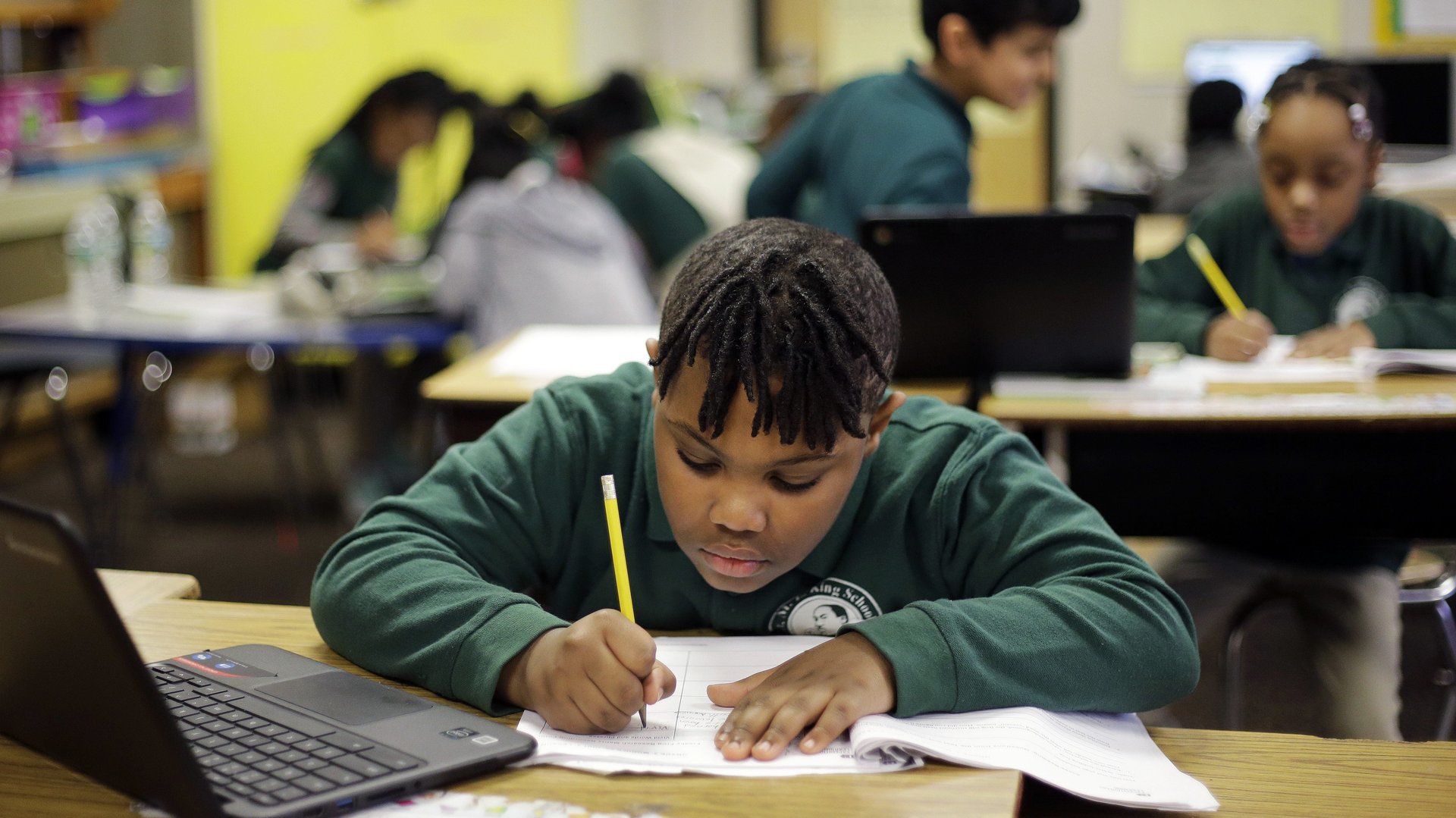

US schools are more segregated than they were in the 1990s

In 1960, Martin Luther King Jr. remarked on the dismal state of school integration. By that time, the US Supreme Court had already declared segregation unconstitutional in its seminal Brown vs. Board of Education decision, yet only a sliver of black students was sharing classrooms with white students in the South. “At this pace it will take 92 more years to integrate the public schools,” he said.

In 1960, Martin Luther King Jr. remarked on the dismal state of school integration. By that time, the US Supreme Court had already declared segregation unconstitutional in its seminal Brown vs. Board of Education decision, yet only a sliver of black students was sharing classrooms with white students in the South. “At this pace it will take 92 more years to integrate the public schools,” he said.

King’s rhetorical deadline is still not up, but if current trends persist, it could take longer than that to achieve his goal. Though schools made big strides in integrating black and white children in the years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, some of those gains have been erased in more recent decades. These days, minority students are less likely to have white classmates than in the late eighties.

The share of intensely segregated schools, those that are 90% to 100% nonwhite, more than tripled to nearly 20% in 2013 from around 6% in 1988, according to analysis by the Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles.

There are several reasons for this. Since the 1990s, the federal government has devoted less attention to desegregation programs. Meanwhile, the number of minority students has grown briskly as white enrollment has shrunk. Those larger numbers of minority students, who also tend to be poorer, tend to go to the same schools in poor neighborhoods. So while white students in general are getting more exposure to minorities, minority students are getting less exposure to white students.

Students of all races are getting more exposure to low-income classmates, but minority students are getting the most. The Civil Rights Project researchers call this phenomenon “double segregation.”

More recent analysis for individual states, from Florida to New Jersey, show the same trends.

This is worrisome on several levels. Poor, minority children who attend poor, segregated schools are getting fewer opportunities than their white peers. This is not only unfair to the minority children, but it also perpetuates inequality in the US.

This kind of separation also exacerbates the deep political and cultural divides that have rendered public discourse in the US so contentious. Thurgood Marshall, another civil rights movement leader and the US’s first black Supreme Court justice, put it this way: “Unless our children begin to learn together, there is little hope that our people will ever learn to live together.”