The Chinese recovery is here. Or… is it?

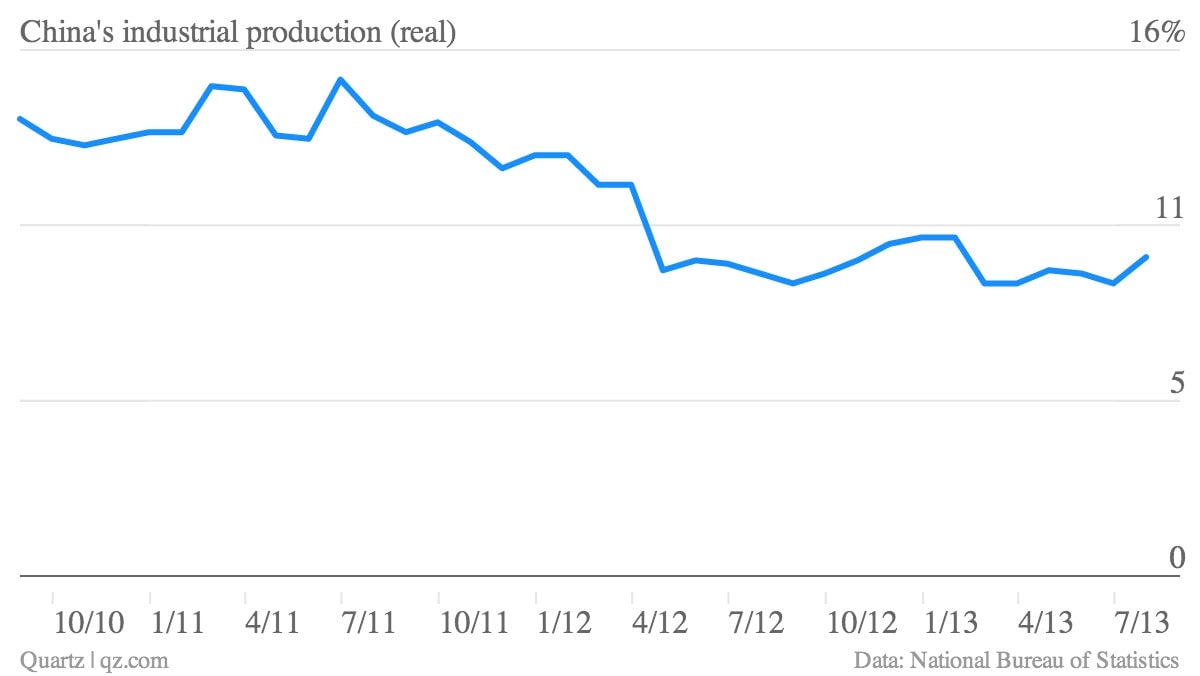

China’s economy may be coming in for a soft landing, by the looks of the latest data on manufacturing output. The “flash” preview of China’s purchasing managers index (PMI) for August came in at 50.1, much better than expected. This came after a resurgence in industrial production in July.

China’s economy may be coming in for a soft landing, by the looks of the latest data on manufacturing output. The “flash” preview of China’s purchasing managers index (PMI) for August came in at 50.1, much better than expected. This came after a resurgence in industrial production in July.

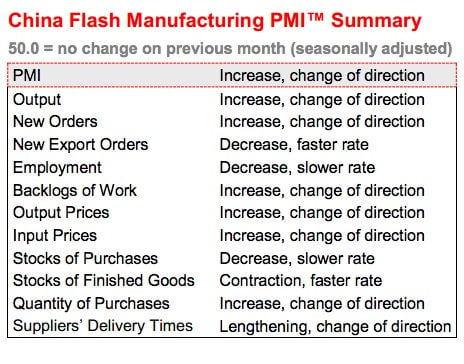

This isn’t a fluke due to recovery in Europe; the PMI showed export orders remained shabby.

The consensus is that China’s economy is strengthening. For instance:

“China’s manufacturing growth has started to stabilize on the back of modest improvements of new business and output” (pdf), wrote Qu Hongbin, the head economist at HSBC, which publishes the PMI survey.

“Domestic demand is strong enough to support 7.5% growth in 2013,” Ken Peng, an economist at BNP Paribas, told Bloomberg. “Almost all of China’s economic data since July has shown improvements and suggests a rebound is underway.” Several investment bank economists noted that China will probably grow 7.7% in Q3 as a result.

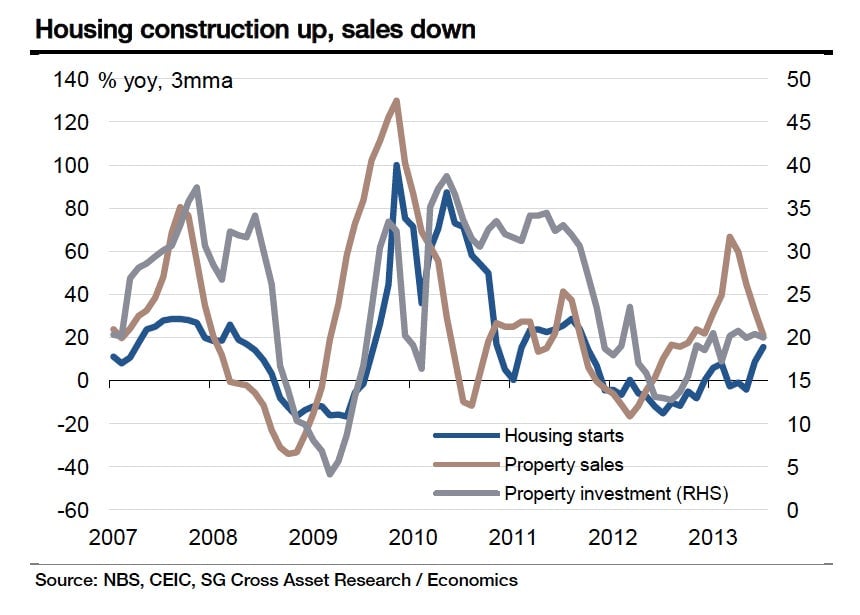

But the question of why and whether the rebound will last is up for debate. Government policy has clearly contributed to the rebound. HSBC’s Qu cited “initial filtering-through of recent fine-tuning measures,” which likely refers to the government’s recent series of tax cuts and investment in affordable housing and railway buildout. Wei Yao of Société Générale flagged government infrastructure investment, though “reviving housing construction is the main factor” she wrote in a note today.

Lu Ting of Bank of America attributes the economic turnaround to “increased confidence as Communist Party leaders indicate a commitment to sustaining growth,” according to Bloomberg.

Party leaders seem committed to “sustaining growth,” and not necessarily through investment. In theory, at least, the recent shift toward fiscal stimulus and away from credit growth should help sustain growth while China sheds some of its debt and reduce excess capacity in certain sectors. (Falling investment in manufacturing, which just hit a decade low, is a good sign.)

But that will require investment in valuable projects, which is hard, especially considering country’s the surfeit of infrastructure in some areas.

If investments spawn projects that don’t generate cash, the money supply tightens, warns SocGen’s Yao. Already, as credit contracts, property sales are sliding from their April highs, which leaves less cash for investment-crazed developers.

That could put drain more liquidity from the shadow banking system and bond markets. And that scenario, Yao argues, “remains the biggest risk factor to economic growth beyond Q3.”