Conservative Californians are fleeing to Texas. Data show they’re in for a surprise

McKinney, Texas

McKinney, Texas

Kevin Korenthal was once a registered Democrat, living in a California suburb. After struggling to keep his small public relations firm afloat for years, he decided to pack up his family and two dogs. Last year, Korenthal moved to McKinney, a conservative community in the outskirts of Dallas, Texas. By that point, he was a self-described Trump supporter.

“California is a lost cause now. I tell people ‘Abandon ship. Go to Texas,’” he says.

Korenthal is part of a wave of Californians fleeing the Golden State’s high cost of living, and more recently, the increasingly liberal agenda of its Democratic-dominated state government. Some California residents have proposed seceding from the state, to start “New California.” Others, like Korenthal, are simply leaving.

Politically, the Lone Star state is the antithesis of California. It’s solidly Republican. Its state leaders are aggressively pro-business, anti-tax, anti-immigration, anti-abortion and pro-guns. And they like to point out the differences between the two states every chance they get, furthering Texas’s reputation as a bastion of conservatism.

But conservatives fleeing California will find that, despite its right-wing bent, the Lone Star State is increasingly plagued with the same problems they are trying to leave behind. That’s because many of their pet peeves, from ballooning home prices to overstretched schools, have more to do with exuberant urban growth than politics.

Gone to Texas

California’s exodus is not new. Since the early 2000s, tens of thousands of Californians have been lured east by the “Texas Miracle,” an oil-fueled economic boom that propelled Texas to the top job creator spot in the country. But even after collapsing oil prices slowed down the Texas economy, Californians kept coming.

From 2010 to 2016, Texas took in the biggest number of domestic migrants of any state, adding 867,000 new residents. California, in contrast, was among the five biggest net losers; it hemorrhaged more than 380,000 residents. On average, nearly 60,000 Californians left their home for Texas every year from 2011 to 2015. The vast majority hailed from the state’s most heavily populated areas, in Southern California and in the San Francisco Bay Area.

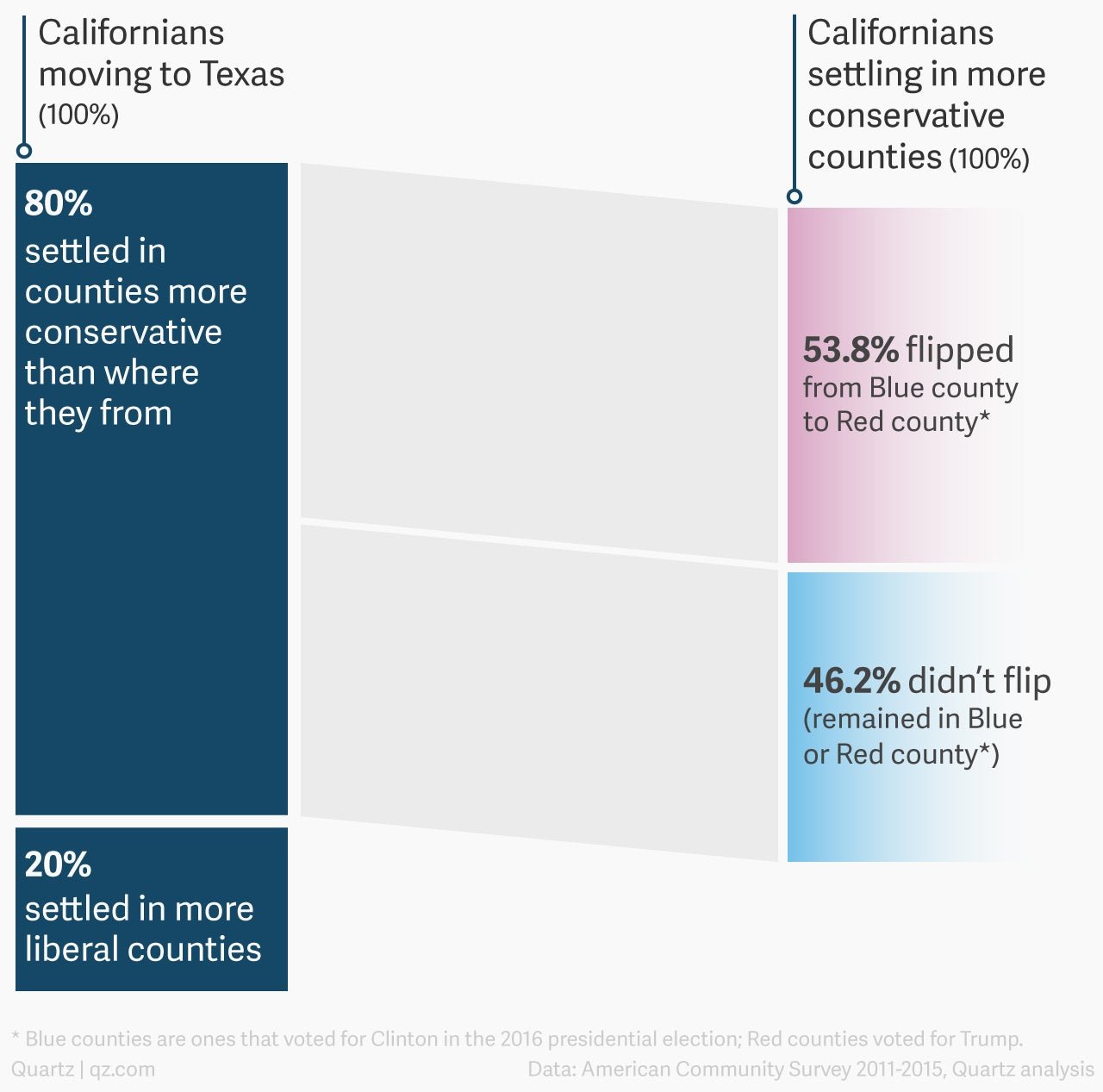

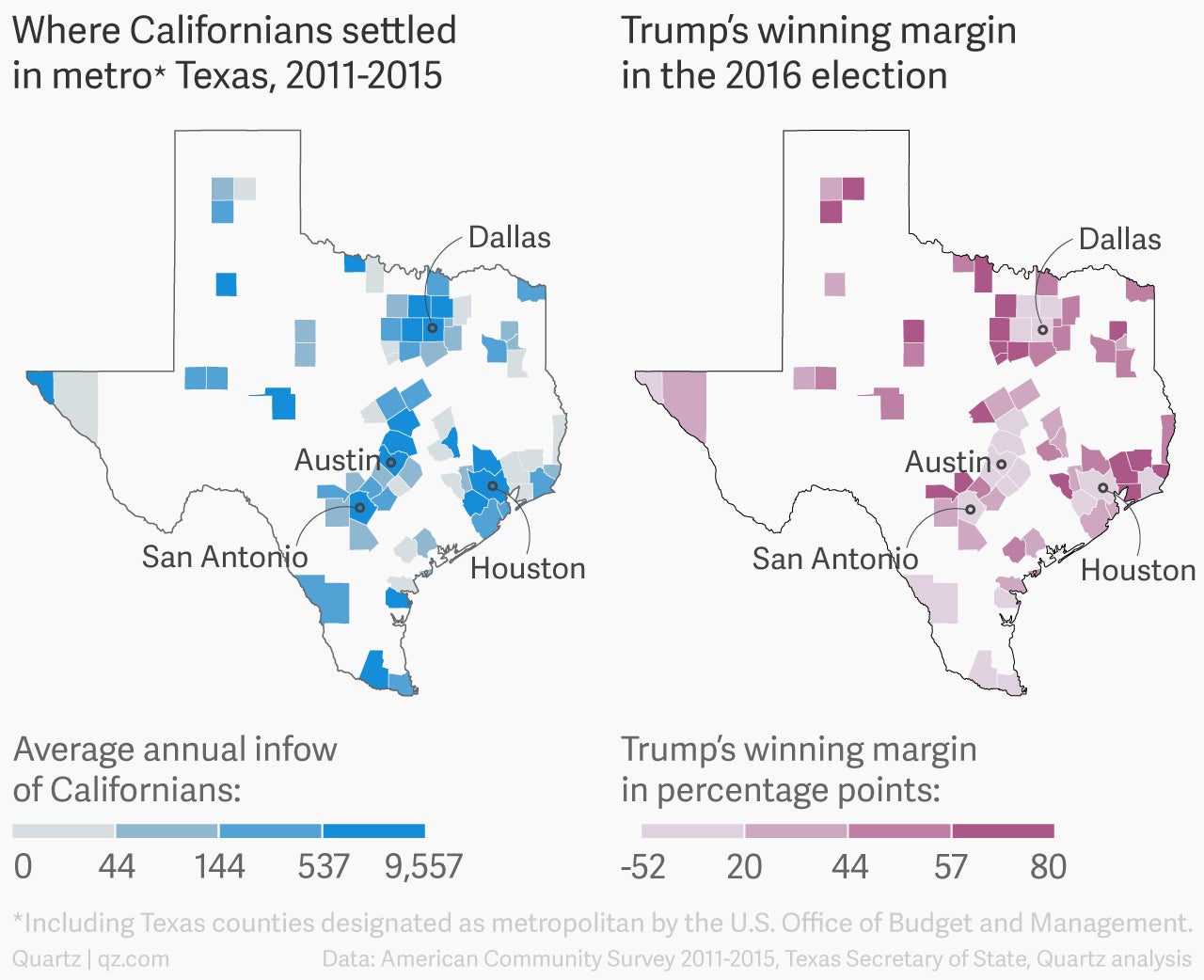

Nine out of ten Californians who defected to Texas landed in a metropolitan area, according to our analysis of US census data from that period. And whether they intended it or not, most ended up in a more conservative place than the one they left.

About half of the California transplants concentrated in the counties where Texas’s top five cities are located: Houston, San Antonio, Dallas, Austin, and Fort Worth. These places are hubs for well-paying jobs in technology, healthcare, and business, and all but Fort Worth tend to vote Democrat in local and federal elections (though none are as left-leaning as, say, San Francisco). The other half of California transplants settled in counties where Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential election.

The data doesn’t show whether the migration is politically-driven. Some California liberals likely ended up in conservative areas, and vice versa. But we do know that for at least some of the transplants, the move was ideological.

Conservative haven?

For Californians frustrated with their state’s liberal politics, the suburbs are the place to head to in Texas. They offer the affordable housing and access to well-paying jobs that Korenthal says have been stamped out by overregulation and high taxes in California.

With the money he made from selling his California home, Korenthal was nearly able to pay cash for a bigger house in Texas. He found a job at Dallas-based trade organization with chapters around the country. Despite taking a pay cut, he says he lives better.

The city has also been a political refuge. In McKinney, no one would berate Korenthal’s wife for sporting a sticker promoting a Republican presidential candidate on her car’s bumper, as she was in California. Here, the family can proudly hang, as they have, a door sign reading “We don’t call 911” decorated with a pair of crisscrossed guns.

He has no plans of ever moving back to California. “That state needs to fail. They drove us out,” he said. “I want that government to fall flat on its face.”

Paul Chabot is another native Californian who fled his state’s politics. Chabot decided to relocate to McKinney after he lost his race to represent San Bernardino County in the US House as a Republican in 2016. He picked the city as his destination based on a magazine article that called it the best place to live in the US.

The move was like traveling back to the California of the 1980s, he says. Everything is clean, he adds. He can send his four kids to public schools, which he rates as excellent. People’s lives are rooted in faith.

McKinney’s numerous church spires and neat subdivisions appear to bolster his points. Though the city is one of the fastest-growing in the country, its quaint central square, with an old-school candy store and Celtic pub, gives it a small-town feel.

Chabot’s transition to Texas was so successful, he says, that he’s built a business around the concept: A relocation agency for other frustrated residents of liberal areas, appropriately called “Conservative Move.” He says his network of real estate agents are currently helping dozens of families find homes in communities such as McKinney around the country.

On a recent Friday, he was preparing to receive a group of would-be-migrants at his office, which is tucked in a development made to look like an Italian village. He laid out brochures touting the area’s public schools, and the housing and business offerings of Collin County, where McKinney sits. Here’s a passage from one:

“In Collin County, you can put in an exciting day at your high-tech job, drive 15 minutes to pick the kids up from their award-winning school, and wave to the neighbors (whom you know well) as you drive up to your new, beautiful home. It’s all possible here.”

But California and Texas are changing in the same ways

For Chabot, his new hometown is a huge upgrade from San Bernardino County, which he describes as a “third-world country.” Crime was rampant and public schools failing, he says. Middle class families like his struggled to keep up with high taxes and rents. It was barely recognizable from the community he grew up in as a kid, he adds.

Census data shows that San Bernardino has indeed changed. From 2000 to 2016, its population surged by 25%. It also became poorer, more diverse, less affordable, and more Democratic.

But the data also show Collin County is evolving along similar lines as San Bernardino. Its population has also swelled—at a much faster rate than in the California county. Over the past decade and a half, Collin, too, has grown poorer, less affordable and less Republican.

Cultural norms are changing, too. Just a few years ago, no one gave a second thought to opening a school function in McKinney with a Christian prayer asking God for a second presidential term for George W. Bush, as The Atlantic’s Olga Khazan reported. These days, that kind of behavior is bound to get pushback.

McKinney Independent School District received complaints last year after its superintendent led a prayer at an all-staff meeting. (In a sign of the changing times, the superintendent acknowledged that it might make some in the audience uncomfortable—though he went ahead with it anyway.) A few weeks ago, two district teachers had to step down over tweets in which they called Islam “a satanic death cult” and said transgender people were mentally ill.

The Californization of Texas?

Areas neighboring Collins County seem even closer to Korenthal and Chabot’s dark picture of California.

Just 30 miles away, Dallas County’s poverty rate is above 15%, just like in San Bernardino, California. Dallas County’s white population has been halved, to about 30%, since 2000—just like in San Bernardino. And Trump supporters in Dallas County accounted for an even smaller share of the voting public than in San Bernardino during the last presidential election: 35% vs 42%.

Korenthal blames the Democratic politics of cities such as Dallas for making parts of Texas look more like California. His theory is that over the long term, areas that embrace liberal policies will collapse under the weight of their own failure. Eventually places like Dallas—and California— will come around to the Texas-style low-tax, light-regulation approach that generates economic prosperity for all sectors of society, he says.

But despite Texas’s stellar job creation and economic growth over the past decade and a half, the state’s poverty rate inched up slightly—to 15.7% in 2016 from 15.4% in 2000—just like in California, where it rose from 14.2% to 14.4%.

Meanwhile, Texas’s economic star has dimmed. The state’s economy shrank by 0.3% in 2016 vs. California’s 3.3% growth rate. (Data for the first three quarters of 2017 show Texas grew much faster than the previous year, and outpaced California.) As in California, the state’s population became less white and its voters less Republican than in 2000.

Home prices across the state have also climbed dramatically. Texas is experiencing a housing crunch, even though its land use regulations are among the least restrictive in the country and developers have more space to build than in California. Incomes, however, have not kept pace. Here’s what that imbalance looks like in the Dallas metro area, which includes Collin County:

There’s also evidence that the pressures from a rapidly expanding and more diverse population have led to at least some of the more socially-minded policies adopted by Texas cities, not the other way around. In Houston, for example, local authorities had to pass new rules to avoid conflicts between existing homeowners and the wave of new developments spurred by its growing number of residents.

Those new Texans are also weighing on public services, such as roads, schools and hospitals. Some of them, the undocumented immigrants who help underpin the Texas dream of affordable housing through their cheap labor, are particularly dependent on those services because they tend to be poorer.

Economists have been telling state politicians they have to cover those needs in order to keep the economy chugging. Even in the midst of the Texas Miracle, in 2013, the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas underscored the importance of this:

“Sustaining prosperity requires making public and private investments in education, English fluency, health care and infrastructure. While costly, such investments will help the state continue to attract the businesses and workers that have been central to its growth and transformation.”

Local officials at the front lines of the population bulge—including some Republicans—are now calling for more public spending.

To be sure, Texas is far from becoming a liberal stronghold. The state government is sticking to its tight-fisted approach to budgeting, and remains allergic to regulation. Gov. Greg Abbott just launched a crusade to limit local taxes.

So, California refugees such as Korenthal and Chabot can rest assured that suburbs such as McKinney will remain conservative havens for years. Still, both men say, Texans shouldn’t become complacent about their conservatism. California, too, was once solidly red, they warn.

This story was updated on Feb. 19 to redact the name of Korenthal’s employer.