The neurosurgeon who redrew the map of the brain

“Brain surgery is a terrible profession,” Wilder Penfield wrote in 1921. “If I did not feel it will become different in my lifetime, I should hate it.”

“Brain surgery is a terrible profession,” Wilder Penfield wrote in 1921. “If I did not feel it will become different in my lifetime, I should hate it.”

Penfield, who would become best known for his work as a neurosurgeon at McGill University and the Montreal Neurological Institute, had much to do with improving brain surgery. He dedicated his life to making neurology a more cohesive field among scientists and physicians, whose fields of study, he felt, could be combined to find new ways to help patients.

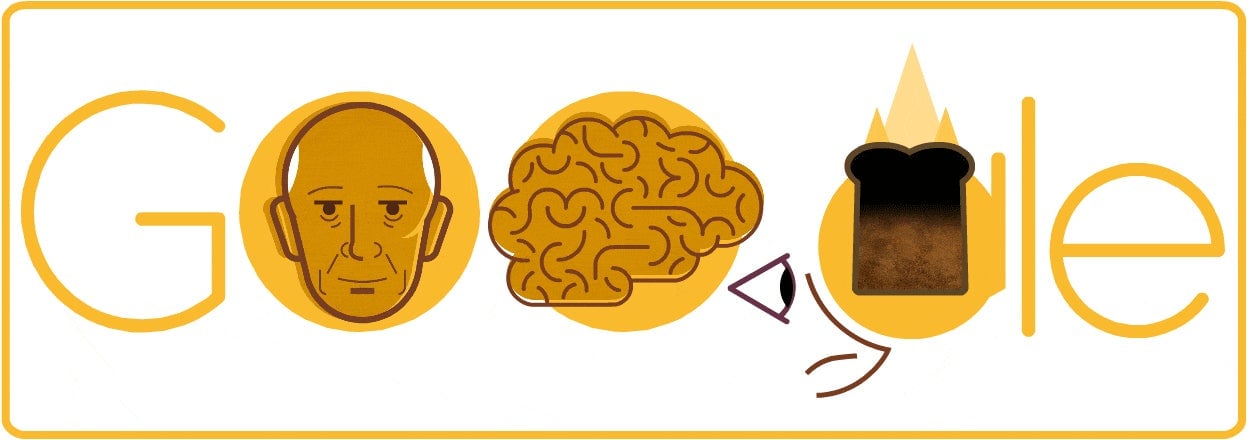

The Google Doodle today (Jan. 26) commemorates what would have been the 127th birthday of the man often hailed during his lifetime (1891-1976) as the “greatest living Canadian.”

Wilder Penfield revolutionized epilepsy treatment

Born in Spokane, Washington, Penfield became a Canadian citizen in 1934 when he founded the Montreal Neurological Institute and became its first director. It was there that he developed a technique to treat intractable epilepsy, now known as the Montreal Procedure.

Penfield focused a lot of his work on helping patients with uncontrollable seizures, who had few options for treatment in the early 1900s. One of his patients reported smelling burnt toast just before she had a seizure, and Penfield realized that if he could stimulate the part of the brain causing her olfactory sense to imagine a smell, he could find the starting point of the seizure. He performed awake brain surgery on his patient (the brain can’t actually feel pain; local anesthetic numbed her skin and skull), and prodded each region with an electrode to stimulate the neurons.

His patient alerted him when she smelled her seizure trigger, meaning the problematic neurons were being tickled, and he was able to cut out that specific part of the brain. Her seizures stopped for the rest of her life, according to Forbes.

How he re-mapped the brain

The Montreal Procedure is what led Penfield to his second great contribution to neuroscience: the sensory map of the brain, envisioned in homunculus models.

After his first success, he noticed that stimulating different parts of the brain lead to patients feeling a variety of sensations: crystal-clear memories in some cases, or tingling in different parts of the body, Vox reports.

This lead to the publication (pdf) of a map of the brain based on sensory perception and the thinking that nerves are a two-way street: The part of the brain responsible for registering feeling in the hand will also cause feeling in the hand, if properly triggered.

Later, this work was used to create homunculus models, little figurines with body parts proportionately sized to correspond with the brain regions devoted to them. It turns out our hands, tongues, lips, noses, and eyeballs have a ton of ties to the brain—much more so than our arms or legs, for example.

This research in part is what has led scientists today to develop brain-computer interfaces that allow users to feel sensations with their robotic arm, and move in more precise ways.