It’s worth betting on a surprise US interest rate hike in 2018

For a decade, inflation has been—as described by of the world’s foremost economists at the central bank for central banks—“stubbornly low” (pdf).

For a decade, inflation has been—as described by of the world’s foremost economists at the central bank for central banks—“stubbornly low” (pdf).

Cheap money, provided by central banks’ quantitative easing has not resulted in price or wage inflation, only asset inflation. This has confounded central bankers and economists, resulting in many questioning the central tenants of monetary economics—namely the relationship between wage and price inflation and spare capacity in the economy.

Now there are signs that inflation is returning in the US. While the most-cited inflation indicators remain relatively stable and within desired bounds, a few key indicators are suggesting that there could be more going on. This has put investors on alert because unexpected inflation suggests there is something new to know about future prices.

Even before US stocks last week had their worst week in two years, inflation was rated as one of the top investor concerns (paywall) for 2018. And the breakeven inflation rate—the difference between the yield of a nominal bond and an inflation-linked bond of the same maturity—has been climbing steadily for the past six months, indicating that investors expect inflation will increase. (It is generally assumed that investors have both the incentive and aptitude to accurately price inflation, so market indicators are often seen as more reliable than surveys.)

Inflation is rigorously tracked—via the consumer price index (CPI) and families of producer price indices (PPI)—on a monthly basis. Each index tracks a multitude of variables. The tricky part is that because a change in inflation is the result of many other changes in the economy that take time to show up (that is, inflation is a lagging indicator), there is a lot of room for judgment in how to assess the many factors.

The Federal Reserve raises the benchmark interest rate in times of economic growth, partly to temper inflation. So far, markets are expecting three interest-rate increases in 2018 from the Fed, after three last year.

We think the inflation narrative in the US will change in 2018, possibly resulting in the Fed—as of today, under new management—adding a surprise fourth rate hike. Here’s what that might take—and the particular metrics we are watching.

Prices

While every measure of retail pricing is trending upwards, one in particular is above its typical range and trending higher: median CPI. The median-price change is the price change that’s right in the middle of the long list of price changes that are used to calculate CPI and, according to new research done by the Cleveland Fed, is one of the better predictors of near- and longer-term price rises.

The Underlying Inflation Gauge (UIG) is also on the rise. The UIG is important because it represents the most robust measure of trend inflation. It is derived from a large dataset, not just price variables. It is based on the premise that if there are trends in other economic and financial indicators then it’s likely that there are trends in underlying inflation.

Producer-price indexes for commodities and materials are generally falling. However, the ISM Manufacturing Index, a survey-based index that sources information directly from the front lines of company supply chains, is rising. When it’s rising, it means that employment, production, inventories, new orders, and supplier deliveries are also rising, which is good news—but is also a potential indicator of imbalances forming. This index has been steadily rising for a couple of years, from a low in January 2016 of 34, to a recent peak of 69, as of November 2017. We are watching closely for any departure from its typical upper limit of around 75.

Wages

Wage stagnation has been an ongoing problem. But wages seem poised to move, and they could move faster than expected. It’s a complex picture in the US but we have narrowed our focus down to a couple of measures.

The National Federation of Independent Businesses surveys small businesses on a variety of labor-market indicators. The NFIB percent raising worker compensation survey is an important insight into the pressure on small business to raise pay. According to the survey, the shortage of qualified workers reached a record high in December, suggesting that wage pressure could build at a rate higher than anticipated.

(While comparable data for January hasn’t been released, the top-line wage growth figure for January supports this trend. Average hourly earnings for all private employees increased to $26.74 in January, from $26.65 in December.)

We are also watching wage growth statistics focused on four particular groups:

- Part-time workers, because they have seen some of the least recovery;

- Young people, because they are a proxy for the ability to switch jobs for a higher wage;

- Lower-skilled workers, because we think the ability to automate low-skill jobs is overstated;

- Metro areas, as a rise may indicate a limit on rural-to-urban migration.

The Fed voters

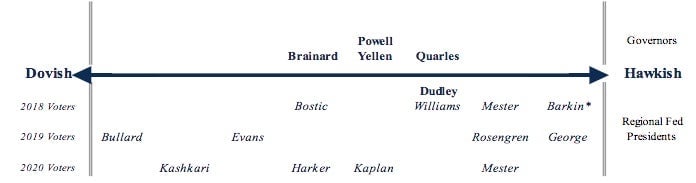

The people who constitute the voting committee—those who decide whether to raise interest rates in response to inflation data—rotate. Not only is there a new chair in 2018, but the voting members for this year represent a shift towards a more hawkish view, according to analysis from BoAML Global Research.

As a consequence, the Fed may start to think harder about what to do about an unemployment rate below its definition of full employment (4.3-5%), even with inflation running close or fractionally below target. If early indicators of price pressure show nuance and employment indicators suggest that there is no capacity in the labor markets, we may well see that extra rate rise in 2018.