Why Eddie Adams’s Vietnam photo still haunts us 50 years later

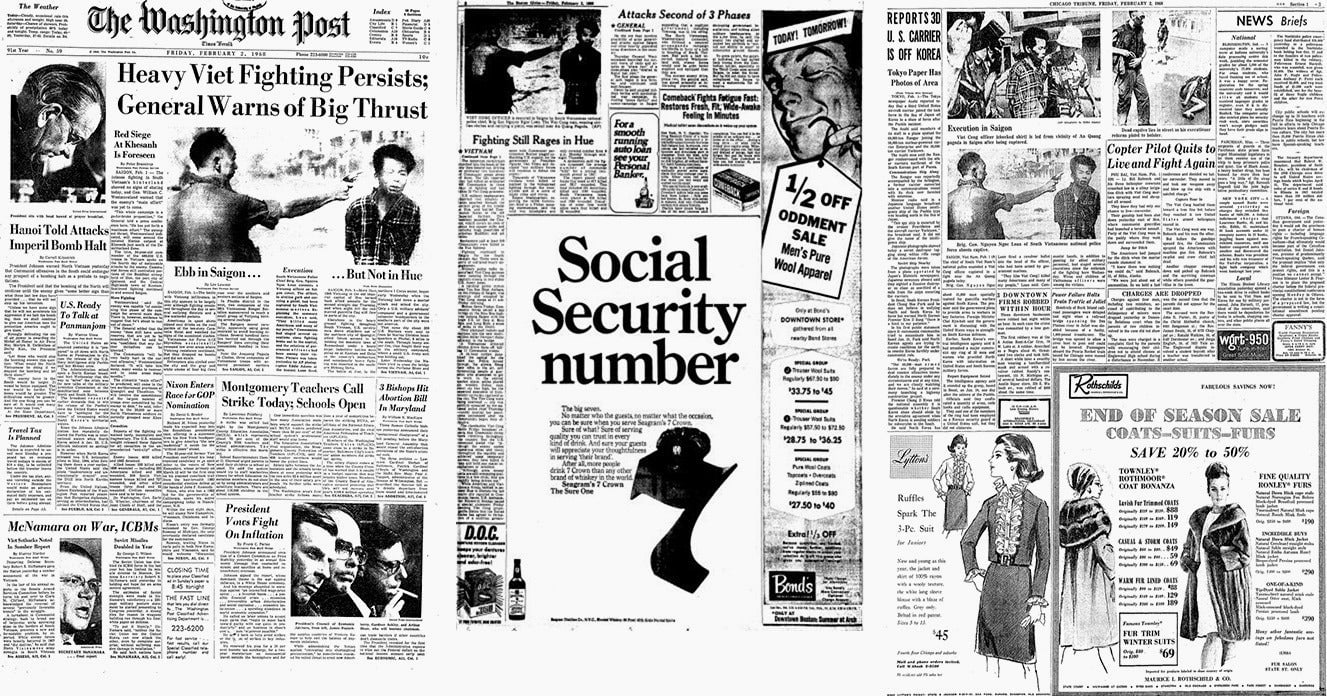

Feb. 1 is the 50th anniversary of one of the most searing war photos ever taken. Instantly recognizable, it shows an impromptu execution: South Vietnamese general and chief of police Nguyen Ngoc Loan, shooting suspected Viet Cong solider Nguyen Van Lem at close range on a Saigon street, during the brutal Tet Offensive.

Feb. 1 is the 50th anniversary of one of the most searing war photos ever taken. Instantly recognizable, it shows an impromptu execution: South Vietnamese general and chief of police Nguyen Ngoc Loan, shooting suspected Viet Cong solider Nguyen Van Lem at close range on a Saigon street, during the brutal Tet Offensive.

The black and white image earned AP photographer Eddie Adams a Pulitzer Prize.

“No war was ever photographed the way Vietnam was, and no war will ever be photographed again the way Vietnam was photographed,” Hal Buell, photo director at the Associated Press for more than two decades, told NPR in 2009.

The photo showed the war’s brutality in a way Americans hadn’t seen before.“You can see the gun, you can see the expression on the man’s face as the bullet enters his head, and you see the soldier on the left who is wincing at the thing that has happened,” says Buell.

“With the still picture, you have time to consider all these factors.”

Most war photos rarely show individual acts of killing; they focus instead on the aftermath of battle, and the effects of the people who live through it. Fifty years later, Adams’s 1968 image remains remarkable for rendering horrifying violence with such clarity.

Adams, along with photographers like Nick Ut and Larry Burrows, have been credited with shifting public perception of the Vietnam War by showing the suffering of American soldiers and Vietnamese alike. It was during the Tet Offensive in particular that these images began to show the American public a much darker view of the war.

“The media coverage of Tet provided reporters with unprecedented access to the images of the conflict as the battles moved into the cities,” Julian Zelizer writes in the Atlantic. Adams’s image, along with others, combined with television footage “confirmed the brutality of this conflict to many Americans” as “coverage shifted from smoke and helicopters to soldiers fighting to recapture ground in a brutal war.”

The Associated Press recounts deliberating over whether to publish the historic image:

At the AP’s New York headquarters, photography director Hal Buell saw the image emerging from the radio-based system used to transmit photos at the time. After some deliberation, he and other editors decided to distribute it worldwide.

“I knew when it went out that you were going to get two reactions. The doves were going to say, ‘See the kind of people we’re dealing with here (in South Vietnam)?’ And the hawks said, ‘It shouldn’t have been used — you guys gotta get on the team,’” says Buell, now retired.

But “the image had an impact, and its impact was felt by those people who were on the fences.”

Today, as war becomes either too dangerous to cover at close range, like the Syrian civil war, or conducted far away from the view of the media, like US drone attacks in Pakistan, it’s unclear if there will be another picture quite like this one ever again

Yet for all the fame this picture bestowed on Adams and his legacy, Adams himself remained ambivalent about it, until his death in 2004. “When I saw the photo I wasn’t impressed, and I’m still not impressed. It’s not a great work of art, in terms of photography,” he says in the documentary An Unlikely Weapon. “I still don’t understand to this day why it was so important.”