Why the Chinese government spent $33 billion on cotton that nobody wants

Texhong Textile Group, one of China’s biggest textile makers, has been shifting production to Vietnam, and the market loves it, reports Bloomberg—the stock is up 445% from a year ago.

Texhong Textile Group, one of China’s biggest textile makers, has been shifting production to Vietnam, and the market loves it, reports Bloomberg—the stock is up 445% from a year ago.

And that’s not because of the much-bemoaned rise of Chinese labor costs. It’s because the Chinese government is making cotton way more expensive than it should be.

Cotton stockpiling: a terrible idea

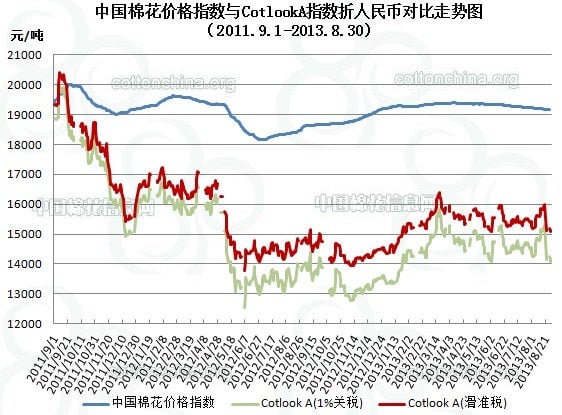

The Chinese government buys and stockpiles domestic cotton when prices fall below a set level, a policy designed to support the textile industry after the 2008 financial crisis swallowed export demand.

The problem? Excess supply has made foreign cotton much cheaper than Chinese cotton. Ever conscious of dwindling profits, companies like Texhong have turned to cotton imports, which has forced the government to shell out $33 billion in the last two years to soak up the excess in domestic cotton, as Reuters reports. In 2012 alone, it stockpiled 89% of China-produced cotton (link in Chinese).

Textile-makers squeezed between pricey Chinese cotton and import limits

Starting in 2013, the government set 3:1 domestic-to-imported cotton quotas for textile factories. Stockpiling was already making cotton expensive for Chinese textile factories, most of which, unlike Texhong, are heavily indebted small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

This year’s import rules made textile manufacturing even less lucrative. “The current business is extremely punishing,” a textile company manager told China Securities Journal (link in Chinese). Alongside rising bank debt and labor costs, the “biggest pressure comes from procuring raw cotton.”

Farmers don’t even benefit from the $33 billion subsidy, since the government buys processed, not raw, cotton for its stockpiles, which means the money goes to refiners (link in Chinese). That’s probably why domestic cotton planting has fallen 6.4% since the initiative’s launch.

The government’s finally cottoning on

Reuters reports that the Chinese government may soon chuck its stockpiling initiative. But the proposed alternative, which would see the government abandon stockpiling and grant farmers subsidies through transfer payments instead, creates other risks.

Giving farmers the money won’t fix the screwy production incentives fueling the supply glut, since subsidies continue to encourage farmers to grow more cotton than the global market demands.

“As long as China maintains this regime to subsidize cotton farmers, the world will be prone to overproduction,” Joe Nicosia, CEO of Allenberg Cotton Co., the world’s largest cotton trader, told Bloomberg last year.

So why keep subsidizing cotton farmers?

The subsidies will likely remain in place for several reasons. Chinese farmers are an important constituency for the Communist Party, given the growing outrage over the yawning urban-rural wealth gap and the ever present threat of unrest by 600 million unruly “peasants“ (pdf). (Also note that the majority of cotton farmers are in Xinjiang, a restive Muslim region in China’s northwest.)

That’s why the government feels compelled to keep subsidizing inefficient small-time, labor-intensive operations that don’t tend to make money. Farms need better technology to produce more. But farmers can’t easily get loans; they can’t use their land or farm equipment as collateral for loans since technically they own it collectively. (For a host of reasons, the government thinks giving 600 million people land rights is unwise.)

But free money isn’t the same thing as a small-business loan. Subsidizing farmers means paying them to make more cotton than the world demands. And that’s a problem for cotton farmers across the world, not just those in China.