I spent a year devising a data-driven approach to behaving ethically. Here it is.

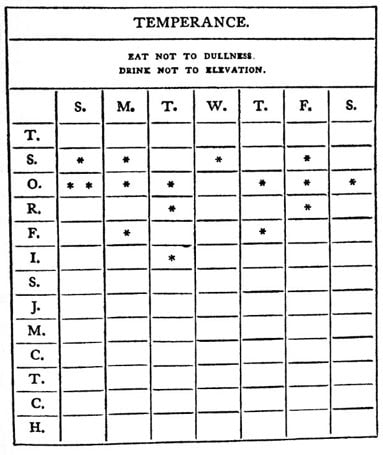

When he was 20 years old, Benjamin Franklin (patron saint of entrepreneurs) wrote down the 13 moral principles he wanted to embody. He sketched a table with principles in the first column, and days of the week in the first row. Each time he caught himself violating a principle, he marked a black dot. Over time, he was delighted to find that the decreasing frequency of dots reflected his progress towards principle-centered living.

When he was 20 years old, Benjamin Franklin (patron saint of entrepreneurs) wrote down the 13 moral principles he wanted to embody. He sketched a table with principles in the first column, and days of the week in the first row. Each time he caught himself violating a principle, he marked a black dot. Over time, he was delighted to find that the decreasing frequency of dots reflected his progress towards principle-centered living.

Today, such a regimented approach to self-improvement seems silly and contrived. Why? We track steps, reps, calories, salaries, likes, and snap scores. But when it comes to our moral selves, we rely on lessons we learned in Sunday School and a vague notion we call “conscience”.

I think that’s the wrong approach.

In an age when data > opinion, it’s foolish to intuit our way through moral self-improvement. By defining and tracking our principles like Ben Franklin did, we can more effectively achieve principle-centered living.

And principles are more important now than ever, because:

Our lives have become “easier” than ever, though not always for the better. 2-day delivery erodes our patience, likes undermine our humility, echo chambers impede our empathy. Faster delivery and more likes may satisfy us temporarily, but only principles, like patience and humility, lead to lasting happiness.

Our environment today is characterized by rapid change, ambiguity, and divisiveness, and grounded, everlasting, universal principles equip us with a reliable framework to navigate the new and exciting problems we face.

Defining and tracking core principles enables principle-centered living in three ways. It helps us to:

- Identify moral behavior,

- Recognize opportunities to demonstrate said behavior, and

- Control your behavior to align with your principles.

Identify

Defining and studying your selected principles helps you identify when principles are being demonstrated—not as cut and dried as it may seem. For example, it’s easy to identify a failure of humility in a pompous, arrogant, caricature.

It takes nuance to identify that your coworker who bemoans small tasks, refuses help, and claims to know better than the bosses is annoying because he suffers from a failure of humility. (I should know, I’ve been that guy). Only by defining and identifying what principles look like in practice can you begin principle-centered living.

Recognize

Defining your principles also helps you recognize opportunities to demonstrate your principles. Again—not so simple. In the heat of the moment, it’s easy to react emotionally to situations, blind to the consequences—like ranting at your direct report about poor performance.

It requires presence of mind and a clear definition of your principles to recognize a colleague’s mistake or frustrating behavior as an opportunity to embody your principles, to react with compassion or kindness. Tracking principles especially helps in hindsight, when you recognize past mistakes as opportunities to improve in the future. Regret can be a cruel yet effective teacher.

Control

Lastly, recording and keeping mind of your principles is necessary to exert the self-control to act accordingly. A vague, unexpressed commitment to “have more courage” begets procrastination and paralysis when it’s necessary to, say, bring up a difficult conversation with your manager.

When you hold yourself to a written record of your failure, like a black dot in a journal, you’re far likelier to muster up the courage to bring up that difficult topic in a check-in.

How to do it

We often think of moral principles as innate or immutable, but I disagree: I think learning to live your core principles is a skill that just requires practice. The first step is to define the principles you want to live by. Choose strengths in addition to weaknesses. Empathy for others might come easily to you, for example, where courage may not. Include both. Then, write them down and figure out a way to track your progress.

One effective strategy is Ben Franklin’s. All it requires is a journal, pen, and a consistent commitment to track your progress towards principle-centered living.

Another strategy I would recommend might sound familiar: the Situation-Behavior-Outcome framework. Choose the principles you want to embody, then each week, think of situations you’ve faced in the past week that have tested those principles. Write down the situation, describe your behavior and whether it aligned with your principle, then describe the outcome or consequences. Do this consistently, and it’ll become easier to catch yourself in the moments that matter.

Whatever your method, the key to improvement is consistency. Changing your behavior can be really difficult, and take a long time. Our behaviors and mindsets can seem hard-wired, a product of our experiences or upbringing (even genetics), and the temptation to feel victim to them is quite strong. But tracking consistently is critical if you want to improve.

The road to improvement will be rife with failure. Even if you desire to be kind, for example, how many times have you lashed out at a roommate or significant other at the end of a long day, when your willpower is low?

I fail every day. But I find tracking and reflection to be a key step towards improvement, and regret to be an effective teacher.

Examples:

Here are 3 of my core principles (2 weaknesses & a strength!), and moments when tracking them has helped me identify, recognize, and control my behavior. Since this is LinkedIn, they revolve around my career:

Humility: Once, in a job interview, a VP-level leader asked me, “if you don’t know something on the job, how will you figure it out?” I rattled off a talking point on my resourcefulness. When that seemed unsatisfying, I realized he was looking for something else—the humility to admit what I don’t know, and to lean on others for help. Humility is a blind spot for me, and I lost myself in the “fake-it-til-you-make-it” mentality and forgot to be humble. Because I defined it as a principle, though, I recognized the opportunity to eat some humble pie, and survived the interview.

Service: Working late one night, I noticed a teammate was still online. As I finished my work, I chatted with him, indulging in some working-late self pity. As we spoke, I sensed the amount of work he had left and the pressure and stress he felt. I signed up to help. I knew misery loves company, and one hour of collaboration always beats three hours alone. I sat down, got back to work, and we completed the project together through “in-the-trenches” misery and laughter. I barely remember the project and definitely don’t remember the work, but I won’t forget the satisfaction I felt that night of serving a friend and teammate.

Patience: One year into my career, I was feeling very impatient at my first job (#millennial). I felt I had mastered the basics of my job (I hadn’t), and was seeking greener pastures. A perceptive mentor, sensing my disengagement, offered me new opportunities for interesting work and learning. I stayed on, and by end of year 2 I was amazed at what I had learned. If I had allowed my impatience to drive me out, I would have forgone the deeper learning and autonomy that is only possible in the second year of a job. By defining patience as a principle I want to embody, I recognize in hindsight the opportunities I almost missed because of my impatience.