Compared to other wealthy countries, US minimum wage isn’t that bad

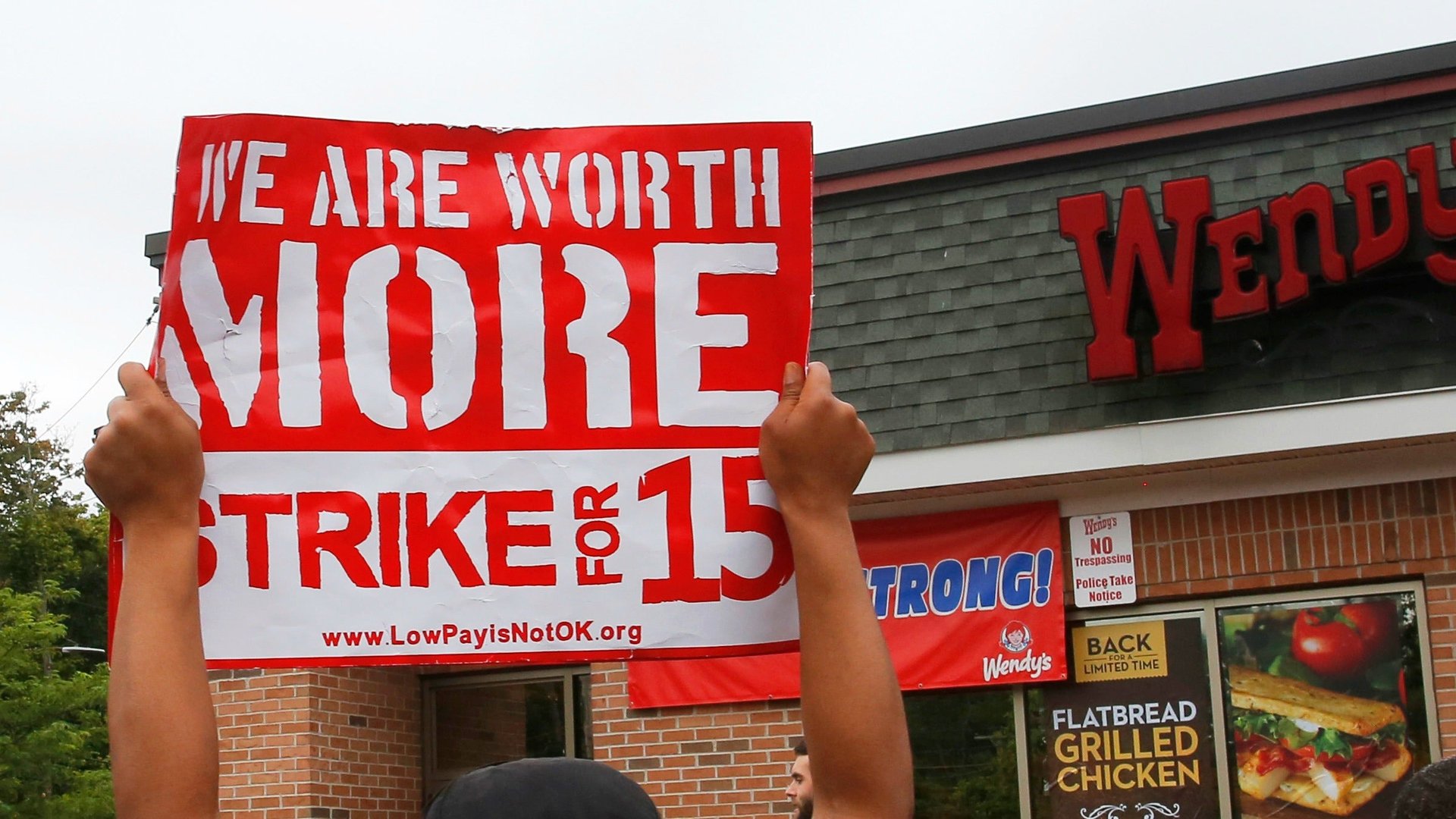

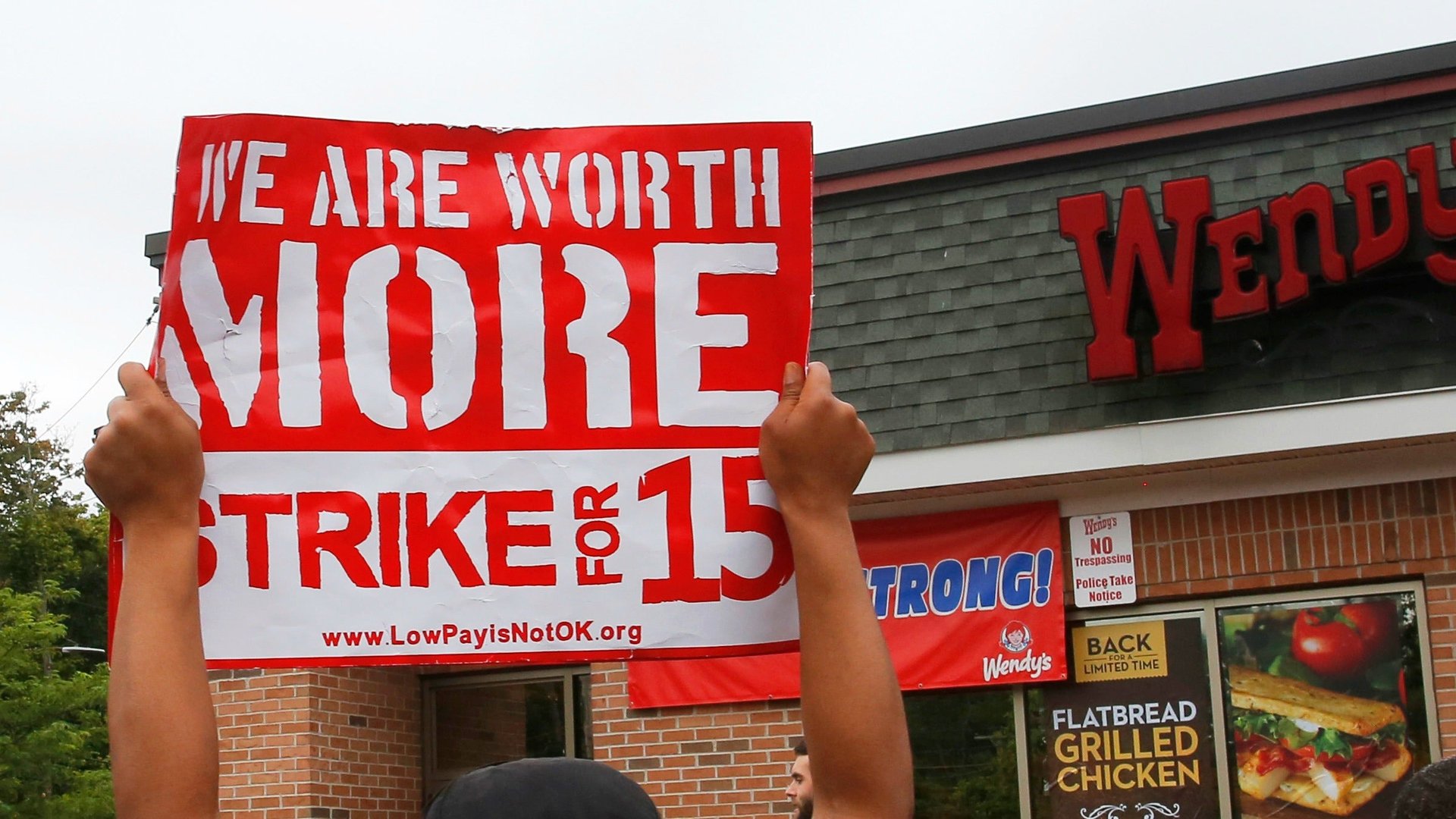

By the standards of other rich nations, the US minimum wage, at $7.25 an hour, can look pretty measly. Australia’s minimum for full-time adult employees works out to almost $15, these days. France’s is around $12. For almost a year now, American fast food workers have been going on strike to demand that kind of pay.

By the standards of other rich nations, the US minimum wage, at $7.25 an hour, can look pretty measly. Australia’s minimum for full-time adult employees works out to almost $15, these days. France’s is around $12. For almost a year now, American fast food workers have been going on strike to demand that kind of pay.

But in some senses, those high wages abroad aren’t quite as high as they sound. The reason: cost of living. Melbourne, where about a fifth of all Australians live, is the fourth most expensive city in the world according to the Economist’s Intelligence Unit—about 36 percent pricier than New York. Making rent and putting food on the table in Paris, meanwhile, is about 28% costlier than in NYC. When it comes to everyday living in these countries, money doesn’t stretch as far as in the states.

Thankfully for us, economists have come up with a concept that lets us adjust exchange rates to account for the differences local prices. It’s called “purchasing power parity,” or PPP. When applied to minimum wages around the world, it tends to even out the differences, a bit. As shown in the chart below, based on 2012 data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Australia’s minimum wage is actually closer to $10 once purchasing power is taken into account. France’s also drops to around $10. Both are still higher than America’s, but not quite as eye-popping. (Scroll to the bottom for the table version of this chart).

So America’s minimum wage workers might not have it quite so awful compared to their counterparts overseas as straightforward exchange rates suggest. That said, there are important factors that PPP doesn’t capture in this case—like the cost of healthcare, for instance. PPP measures prices from an economy-wide perspective, but it doesn’t take into consideration who’s paying for what. So while a Canadian or French McDonald’s worker gets socialized medicine, an American worker either has to devote part of their paycheck for the company plan, get private insurance, or go without (in some cases, Medicaid might be available, and starting in 2014, more adults will be covered in states that have expanded it under Obamacare, but you get the picture).* PPP won’t account for that. A similar story would apply to higher education.

So to review: when you take buying power into account, the US minimum wage stacks up a bit better compared to other rich countries. But only a bit.

*Update Sept. 2, 7:25 PM: As a few commenters have rightly pointed out, I neglected to note that Medicaid is available to at least some minimum wage workers, depending on the state and their exact circumstances. I don’t think it changes the general point too much, but the fact should be mentioned.

Jordan Weissmann is a senior editor at The Atlantic.