How the soccer transfer market turns Europe’s economic story upside down

Bale beɪl n [Welsh] (2013)1 : A denomination of euros equal to 100,000,0002 : informal A very large indeterminate number <he made Bales of money in the market >

Bale beɪl n [Welsh] (2013)1 : A denomination of euros equal to 100,000,000

2 : informal A very large indeterminate number <he made Bales of money in the market >

The close of the window for transferring players in and out of Europe’s largest soccer leagues closed on Monday. A number of records were set.

Teams in the English Premier League spent an estimated £630 million ($980 million) on players during the latest transfer window, the period twice a year in which clubs are allowed to buy and sell players. This smashed the previous record, £490 million, set last year. Lucrative television deals generate more than £3 billion in annual revenue for the league, and teams are clearly not shy about spending it.

Meanwhile, Welsh winger Gareth Bale set the individual transfer record, moving from Tottenham in London to Real Madrid in a deal worth €100 million ($132 million). This pipped his new teammate, Cristiano Ronaldo, for the title of world’s most expensive player. (Ronaldo was sold to Madrid for a mere €93 million in 2009.) It also established a new unit of measurement: the “Bale”. Microsoft bought Nokia for 55 Bales.

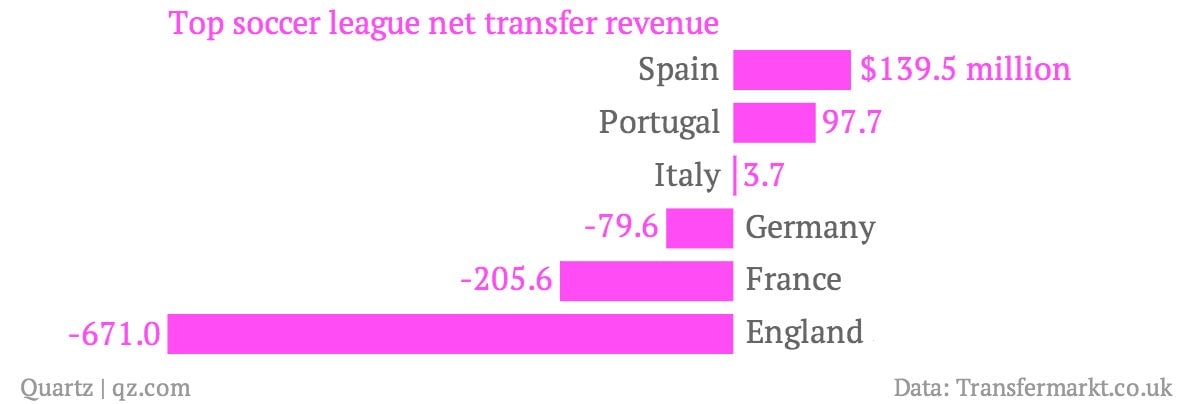

But beyond the gaudy headline numbers, there is a noteworthy pattern at the national level, as the chart above shows. If you take each country’s top league as a whole, net spending flips the common economic narrative on its head. Northern Europe shows a taste for aggressive deficit spending—led by England, with France and Germany doing their part—while the prudent periphery—Spain, Italy and Portugal—collects more than it pays out.

Despite Madrid’s spending spree, on balance La Liga in Spain brought in the equivalent of $140 million more in fees than it spent on players. Levies on this revenue would represent a welcome fillip to the beleaguered Spanish state—if the country’s clubs actually paid their taxes, that is.