The US can no longer rely on small businesses to produce job growth

The entrepreneur is our economic folk hero. He keeps the economy fresh and, most importantly, creates jobs. A major source of new jobs is very successful small firms that grow into larger companies. But new research by University of Florida Cordell professor of finance, Jay Ritter, suggests that becoming a large, independent company is no longer the goal of many start-ups. Technology and globalization has changed incentives. Now instead of growing big and going public, it is often more profitable to grow a little and then be bought by an older, large firm.

The entrepreneur is our economic folk hero. He keeps the economy fresh and, most importantly, creates jobs. A major source of new jobs is very successful small firms that grow into larger companies. But new research by University of Florida Cordell professor of finance, Jay Ritter, suggests that becoming a large, independent company is no longer the goal of many start-ups. Technology and globalization has changed incentives. Now instead of growing big and going public, it is often more profitable to grow a little and then be bought by an older, large firm.

Former Pay Pal COO David Sacks recently declared, on his Facebook page, that Silicon Valley as we’ve known it is over. He claimed that technology is now dominated by large firms trolling for new ideas and start-ups cannot compete with them on their meager seed capital. More start-ups sell their innovations to big companies rather than become the next Facebook or Google themselves. Mr. Ritter reckons that’s not only true in Silicon Valley; it is an economy wide trend.

This might not only transform entrepreneurship, but it also raises the question: Before most new jobs came from small firms growing into bigger firms, now many small firms don’t grow that large—where will new jobs come from? Both political parties laud small businesses as the engine of job growth. Economic studies have found that firms of all sizes and age hire and fire, but very successful, young, small firms can claim credit for most net job growth.

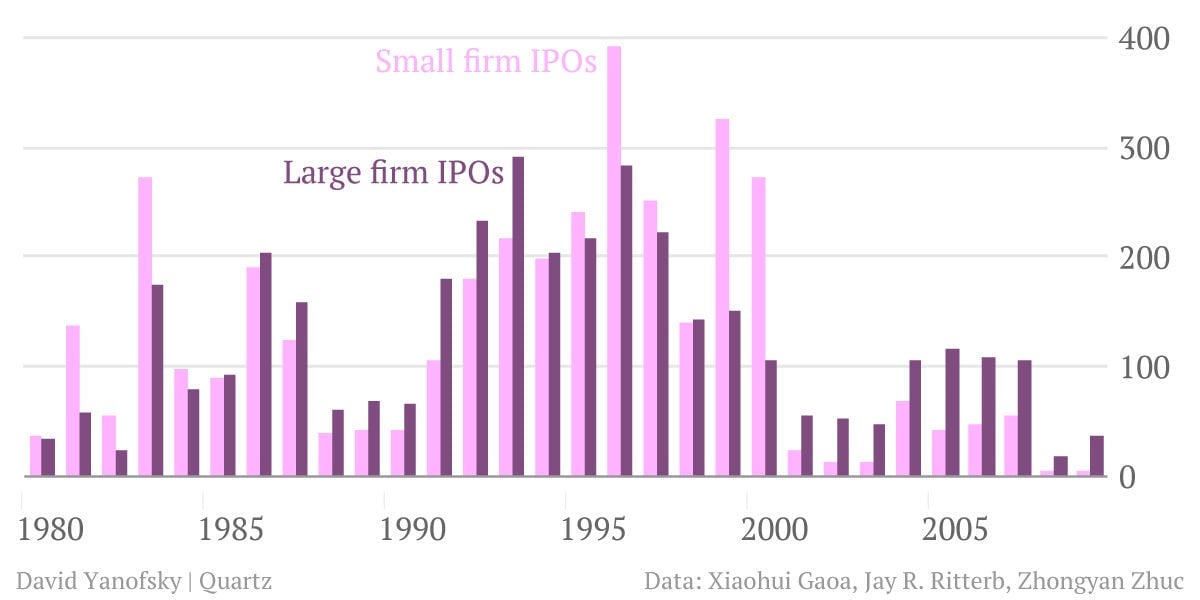

Historically, successful start-ups funded their expansion by selling shares in public equity markets, launching with an initial public offering (IPO). Mr. Ritter calculated that 62% of employees at growing companies were hired after the IPO. But now fewer companies go public. Between 1980 and 2000 there were, on average, 311 IPOs a year. Since 2001, the average fell to 99 each year. The last decade’s decline in IPOs is apparent even when you control for the two recessions, which normally dampen IPO activity. Much of the decline can be attributed to small firms. Since 2000, the average number of small companies that went public per year was 30; between 1980 and 2000, it was 165. Fewer IPOs is often blamed on new regulations and the unsavory behavior of large banks that often underwrite IPOs. Each of these has made selling equity in public markets less attractive, especially for small firms.

But Mr. Ritter’s research suggests that even if those costs were eliminated, many start-ups would still not want to go public. It is more profitable to be bought by a pre-existing large firm than grow into a big firm. He believes a structural change has occurred in the economy which he calls “economies of scope.” Technology and globalization have shrunk the time a start-up has to commercialize its innovation. Previously, firms had more time to grow organically and with it the capacity to execute their innovation on a large scale. But now markets move faster and are more competitive. Commercializing an innovation successfully requires the infrastructure large firms already have in place. In this new world he says it’s “eat or be eaten.”

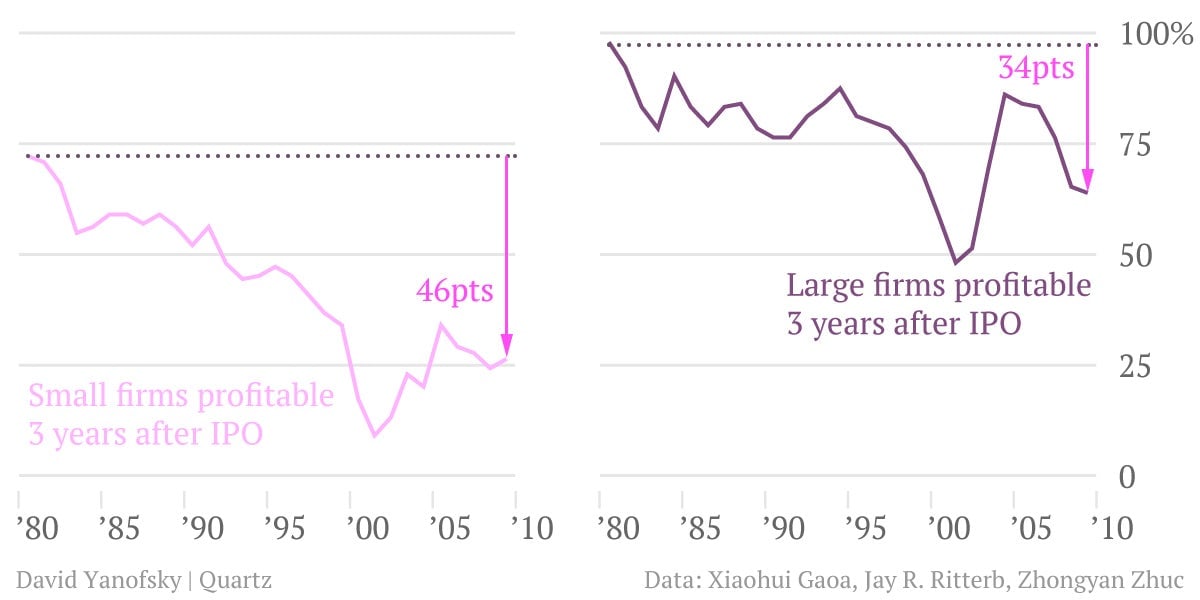

To test economies of scope Mr. Ritter looked at firm profitability. If it has become harder for small firms to compete, then fewer of them would be turning a profit. Mr. Ritter did observe that the percentage of profitable, small, public firms has been declining. Meanwhile profitability among large companies did not decrease as much.

Mr. Ritter also observed that the number of small public firms involved in acquisitions (either bought by a large firm or buying another firm) has been increasing since the 1990s. This is not only true in technology; he saw these trends in other industries too.

In some ways this could be a positive development. Markets constantly evolve and alter the definition of a successful business model. Economies of scope could mean more new products are available and that benefits consumers. It could also mean more entrepreneurs and innovation.

However, different incentives can change in the nature of innovation. In the technology sector some acquisitions are companies that were never meant to get large. Take Instagram, a mobile photo-sharing program, which was just bought by Facebook for $1 billion when it had just 11 employees. How many more people would it have hired if it stayed independent and grew on its own? A start-up based on an iPhone app probably doesn’t have the potential to grow into a Fortune 500 company. Some entrepreneurs today may be attracted to innovations that can be sold off quickly rather than ones that have the potential to transform the market.

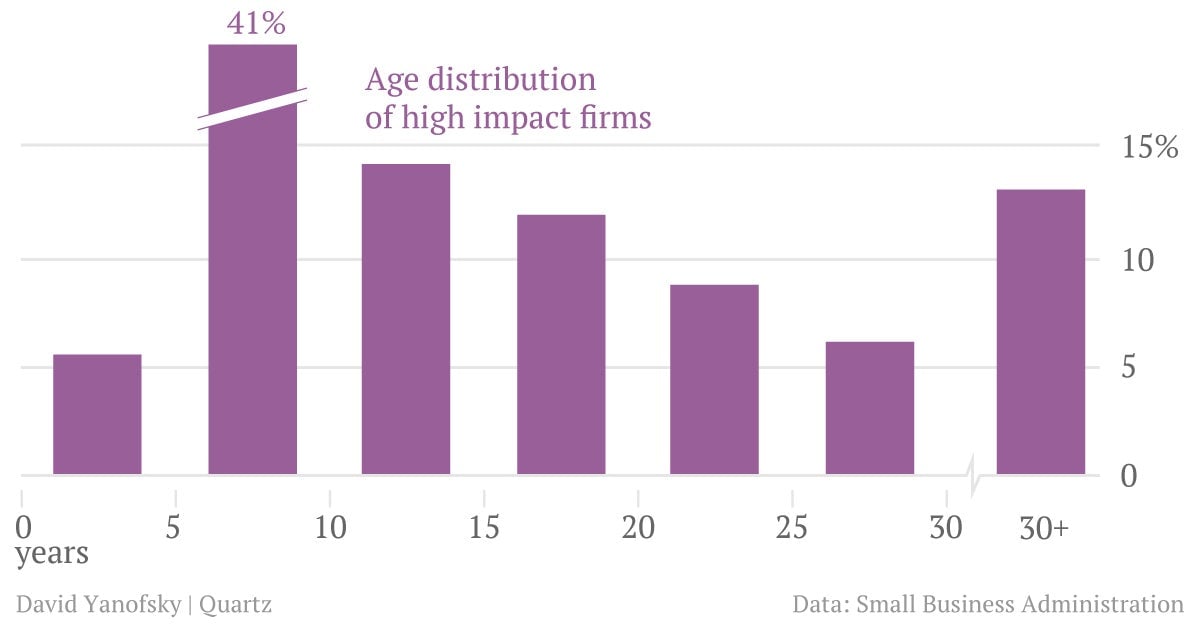

The hot question is what does it mean for job creation? Historically, fast-growing small firms created many new jobs, according to research from George Mason University professor Zoltan Acs, who studies firm size, age and job creation. These job-creating companies are called high-impact firms. Only about 6.3% of firms are high-impact, but they are responsible for nearly all net job growth. They are remarkable, not only because of the number of jobs they create, but how fast they grow. About 94% of high-impact firms have fewer than 20 employees when they entered the job-creating phase. If small firms are bought out early instead of growing large will they create the same amount of new jobs?

Mr. Acs is concerned they won’t. He believes that if small firms don’t have the time to grow organically it will inhibit job growth. A start-up successful grows quickly, but it can take several years to reach the high-impact phase. According to Mr. Acs job-creating firms are usually not over-night sensations. The figure below is the distribution of small, high impact firms by age between 2002 and 2006.

Ron Gonen, currently New York City Deputy Commissioner for Recycling and Sustainability, started a high-impact company and teaches entrepreneurship at Columbia Business School. Fresh out of his MBA in 2004 he founded RecycleBank, which provides incentives to recycle and practice good green behavior. The company started with just Mr. Gonen and his co-founder, but now it employs 150 people. Mr. Gonen stepped down as CEO in 2010. RecycleBank is still privately owned, but the hope is it will either be acquired or maybe go public. Mr. Gonen believes the changes we see with start-ups reflects that they’ve become more focused on short-term pay-offs rather than building long-term value. He faults venture capital firms, who provide early financing and have a say in how the start-up is run. The nature of venture capital fund raising means many fund managers want to realize short-term profits early rather than build the start-ups’ long-term value.

The experience of RecylceBank shows that start-ups will still create jobs, but it may come from the getting-to-be-acquired stage. According to Mr. Ritter more than a third of employees at growing companies were hired before the firms went public. How many jobs are created or destroyed after an acquisition is not well understood. Presumably there will be some hires, though there might also be lay-offs. It seems growing a company from scratch would mean more jobs than an acquisition. Larger companies already have the support and technology staff that a growing company might otherwise hire. Mr. Ritter speculates this will mean the old model of lifetime employment will become obsolete. Having amendable skills and the ability to change jobs will increase in value. There may be more serial entrepreneurs and people who will make their careers working for different start-ups.

There may be fewer start-ups that grow into large firms, but the model of building a business that remains independent will probably never completely disappear. There will always be some entrepreneurs who’ll want to build a company and make it their legacy. Jon Stein, who founded Betterment which provides low-cost investment advice to the masses, is what’s becoming that rare kind of entrepreneur. He started the company four years ago, has 20 employees and is looking to hire more. He bristles at the thought of selling his business to a large bank. He feels his business model, good value to small investors, is not consistent with the model of many large, financial service firms. Also it frees him from conflict of what financial products he recommends to his customers. He’d like to see his business stay independent and grow to a $100 million dollar company. Though, idealism may have a price. According to another young entrepreneur, Alexey Sokolin who founded financial soft-ware start-up Nestegg in 2010, “if someone offers you millions of dollars for your company it transforms your life; and that’s hard to walk away from.”