What China’s Xi Jinping wants with all that power

Chinese president Xi Jinping has amassed so much power that he’s been called the “chairman of everything.” Now China appears set to make a move that would allow Xi, already the most authoritarian Chinese leader in generations, to stay in power perhaps for life.

Chinese president Xi Jinping has amassed so much power that he’s been called the “chairman of everything.” Now China appears set to make a move that would allow Xi, already the most authoritarian Chinese leader in generations, to stay in power perhaps for life.

What does he want with absolute power?

That’s a question many are asking after China’s Communist Party proposed on Feb. 26 to erase the two-term limit for the presidency from the country’s constitution, which the National People’s Congress is expected to ratify as it gathers at the annual Two Sessions meeting.

Xi often speaks of the importance of the “rejuvenation” of the Chinese nation, and of the ambitious and tricky tasks the country must navigate over the next 15 or so years: become more uniformly prosperous, repair the environment, and turn China into the world’s biggest power. To do all that, Xi believes that the party must be at the center of everything, and he himself at the center of the party.

“Taking on responsibilities means fulfilling one’s office diligently,” Xi said in a speech in 2015. ”Decisions and plans must be executed in full, and one must see things through from beginning to end, to ensure that no one simply goes through the motions or treats plans as a temporary measure, like a passing gust of wind.”

An autocrat with a love for “rule of law”

The history of the office of president—which some have noted isn’t quite the right translation of the Chinese term for the title—is itself a reflection of the party’s paradox between one-man rule and collective leadership.

First established in 1954, the presidential position was held by Mao Zedong until 1959, when it was assumed by his chosen successor Liu Shaoqi. But both Liu and the presidency fell victim to Mao’s decade-long, traumatic Cultural Revolution from 1966 to combat capitalism and persecute political rivals. In 1975, Mao pushed through a new constitution that emphasized the party’s rule over the state, eliminating the office.

After Mao’s death in 1976, Deng Xiaoping, who had been a political target, returned to the inner circle of the party, and soon maneuvered his way into becoming its most powerful leader. He quickly decided to introduce collective leadership—highlighted, among other things, by a power-transfer mechanism—to prevent the rise of another Mao-like personality cult. In a new constitution ratified in 1982, the presidency was restored with a two-term, 10-year limit. A retirement rule for Chinese officeholders was put in place for the first time, and China was set apart from other authoritarian regimes by having a process for orderly leadership succession.

But the office is still not the most important political title in China.

True power actually lies with the rank of general secretary of the Communist Party’s Central Committee, as well as chairman of the Central Military Commission. Xi holds both titles, neither of which come with term limits. For this reason, continuing as president isn’t a prerequisite for remaining the most powerful man in China.

For example, Xi could retire from the presidency as due in 2023, while keeping the party and military chief roles. It’s also possible for him to keep his grip on power from behind the scenes even without those titles. Deng was China’s most prominent leader throughout the late 1970s and the 1980s, but was never party chief or president (though he was military chairman from 1981 to 1989). Yet he was responsible for the dramatic reforms that lifted his country out of the chaos of Mao’s rule to transform China into the power that it is today.

Xi, who spearheaded a dramatic crackdown on corruption and dissent, as well as a slew of legal reforms under the rhetoric of “rule of law,” may not want to do things that way. “It might be that he has less faith in the efficacy of informal power versus more formal institutional power, and that might be a lesson he learned from Deng’s experience,” Sam Crane, a Chinese politics expert at Williams College in Massachusetts, told Quartz.

Collective leadership, Crane notes, created serious trouble for Deng as he tried to control political developments without holding the key offices. Deng’s initial two picks as his successors—Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang—were later removed amid pressure from other party elders. When Deng nominated a third, compromise candidate, Jiang Zemin, after the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, Yang Shangkun, who was president, hampered his efforts to consolidate Jiang’s power.

“When thinking about political questions, how to manage power to enact what he believes should be China’s path forward, Xi is less of a Dengist and more of a Stalinist-Maoist,” Crane said. “Therefore he does not want to leave open any institutional doors, even those that seem relatively insignificant, that might allow others to challenge his authority.”

A Gorbachev for China? Nyet

After taking power in 2012, Xi asked his colleagues in a leaked internal speech: “Why did the Soviet Union disintegrate? Why did the Soviet Communist Party collapse? An important reason was that their ideals and convictions wavered.”

Under Xi, the idea that there can be no government without the Communist Party—in fact, the party outranks and controls it—has been reinforced so as not to repeat what he sees as the errors of the Soviet Union’s Mikhail Gorbachev, known in China as the leader who led an empire to collapse.

“Finally, all it took was one quiet word from Gorbachev to declare the dissolution of the Soviet Communist Party, and a great party was gone,” Xi said. “In the end nobody was a real man, nobody came out to resist.”

The undoing of the presidential term limit “dovetails with the broader theme of Xi’s period in office—of the party erasing distinctions between it and the state,” wrote Richard McGregor, senior fellow at the Lowy Institute in Australia and author of The Party, last week.

Soon after taking power, Xi created and headed several secretive party organs called “leading groups” that steer everything from economic reforms to cyberspace affairs, sidelining existing government agencies that already have a say in these areas. At the start of the party’s 19th national congress in October, Xi borrowed a line from Mao: “Government, military, society, education, north, south, east, west—the party leads everything.” The quote was later enshrined in the party’s charter.

Xi’s move “makes sense with how he views both Gorbachev’s and [his predecessor] Hu’s [Jintao] governance failures—basically that they allowed the state to strengthen at the expense of the Party, straining the linkage between the two and allowing for the existence of a state without a Party,” wrote Jessica Teets, a political scientist at Middlebury College in Vermont.

Seize the day, seize the hour

Once he’s strengthened the party, and his spot at the top of it, Xi’s most pressing agenda is the realization of “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”—also known as the “Chinese Dream”—a term Xi put forward shortly after taking power in 2012.

To fulfill this great dream, Xi must accomplish the “two centennial goals” inherited from earlier leaders. The first involves building a “moderately prosperous society,” wiping out poverty and reaching a per capita GDP of $10,000 by 2021, the 100th anniversary of the party’s founding, which is almost certain to be achieved. The second and more challenging goal is to turn China into a “fully developed nation” by 2049, the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic. If it succeeds, China’s economy would be triple the US’s, according to an IMF estimate. At the party congress in October, Xi for the first time outlined a specific timetable for reaching the second centennial goal.

He said the party will first lead China to realize “socialist modernization” by 2035—which will involve, among other things, reducing inequality and improving the environment. In the second stage, from 2035 to 2050, China will become a leading global power.

“The basis of the CCP’s rule for the last forty years has been performance legitimacy. The country gets richer so everyone benefits by having its own particular brand of one-party rule,” David Goodman, a professor of China studies at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University in China, told Quartz. “Continued growth and the continued leading position of the CCP now, though, both depend not just on sheer growth but on more equitable distribution of the benefits of growth.”

Xi might also have learned from the rise of populism in the US, the UK, and Europe that “where the people don’t benefit equally from global economic growth, they will turn on their establishments,” Goodman says.

The Global Times, a populist state-run tabloid, justified the constitutional amendment in an editorial by saying China needs stable leadership right now:

China cannot stop and take a break. Our people believe that every year is crucial. The [Communist Party] has made development goals to be achieved in 2035 and 2050. The country must seize the day, seize the hour. Our country must be united, energetic and be able to continue with opening-up. Our country must not be disturbed by the outside world or lose our confidence as the West grows increasingly vigilant toward China.

Another item on Xi’s to-do list is to bring self-governing Taiwan back under Beijing’s control. At the party congress, Xi identified reunification with Taiwan as a major component of the “great rejuvenation” of the Chinese nation. As some analysts noted at the time, that means Beijing must seize control of Taiwan by 2050 at the latest.

“The only thing that will make him the greatest leader in the Chinese Communist Party’s history is to take Taiwan back,” Shen Dingli, a foreign-relations expert at the Fudan University in Shanghai, told Quartz. “If he were to achieve China’s reunification, who will say he is second to Mao Zedong or Deng Xiaoping?”

China, the center of the world

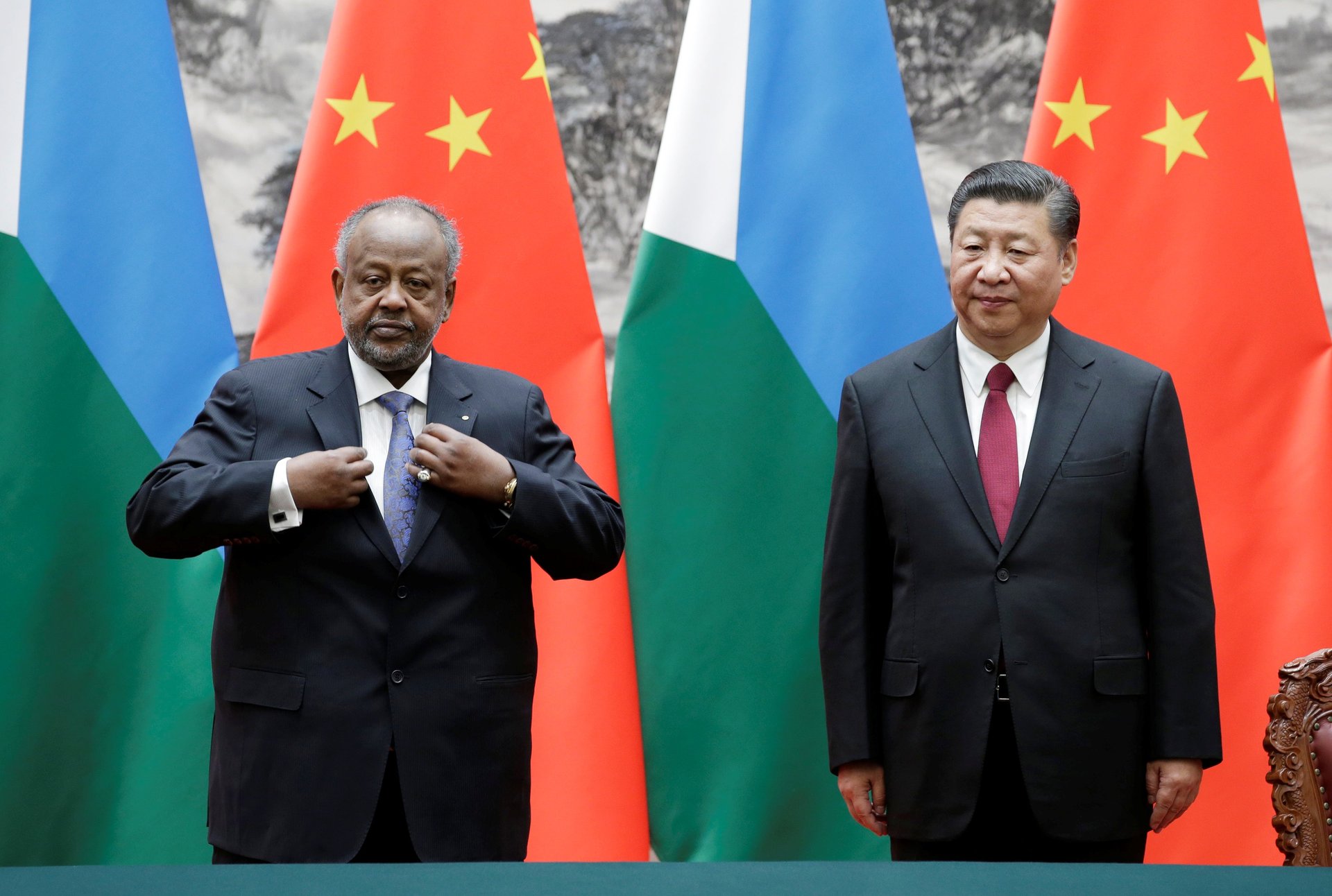

Another reason for Xi to remain in the presidential role is because the job is becoming more important than ever, partly thanks to his global ambitions. Xi “could hardly have made his globe-trotting round of state visits as head of the Party… but he also needed the post to have real resonance,” wrote Jonathan Fenby, China chairman at the TS Lombard research service.

Since taking power, Xi has embarked on a trillion-dollar infrastructure spending spree that aims to connect more than 60 countries spanning across Asia, Europe, and Africa, called “One Belt, One Road.” For years, China has been building military facilities on top of real and artificial islands in the contested South China Sea. In August, the country opened its first overseas military base in the Horn of Africa.

Last year, Xi positioned himself as globalization’s most vocal champion in a big coming-out speech in Davos. Ever since then, the narrative that China is poised to fill the global leadership void left by the US under president Donald Trump has only grown stronger. In January, the party’s top newspaper called on China to seize the “historic opportunity” to reshape the world order, as “the world has never focused on China so much and needed China so much as it does now.” Later, during this year’s Davos, state media put the message more bluntly: The world should choose from Xi’s “shared future” vision and Trump’s “America First” policy, two opposite outlooks for the state of the world.

Xi himself has declared a “new era” that sees China as a top global power. “It will be an era that sees China moving closer to center stage and making greater contributions to mankind,” Xi said at the party congress.

Xi means what he says “about putting China at the center of the global stage, and his indefinite purchase on the presidency forms part of that,” argues Fenby. “Symbols matter and a message has been sent, not only inside China but also to the world.”