Silicon Valley’s libertarians are trading blows with California Democrats in a fight for the left.

The progressives are taking over the Democratic party. So far, their message of economic populism has mostly focused on Wall Street and big corporations. Now they are increasingly turning their rage against Silicon Valley.

The progressives are taking over the Democratic party. So far, their message of economic populism has mostly focused on Wall Street and big corporations. Now they are increasingly turning their rage against Silicon Valley.

The tension between progressives and tech libertarians has been growing for a while: While progressives support reasonable government regulations, libertarians believe that business and innovation will thrive only if the government stays away.

Until now, Democrats have mostly stayed out of the fight by avoiding calling for policies that might temper the growth of the tech giants. But that’s about to change. We’re currently witnessing a perfect storm, where the force of the post-election backlash against “big tech” is coalescing with the rise of progressive activism across the country. And Silicon Valley is right to be scared.

At the California Democratic Party convention last week in San Diego, the increasing tensions with big tech were apparent. Democratic speakers called Elon Musk a “union-busting asshole,” lobbied for new antitrust laws against tech monopolies, urged stronger regulation of ride-sharing companies, and proposed a bill to prohibit digital bots as well as an ambitious new ballot initiative, the California Consumer Privacy Act, which wants new regulations for the tracking of consumer data. This act would give consumers the right to know what data companies are collecting, the right to choose what data they can collect, and regulate the selling of information to third parties.

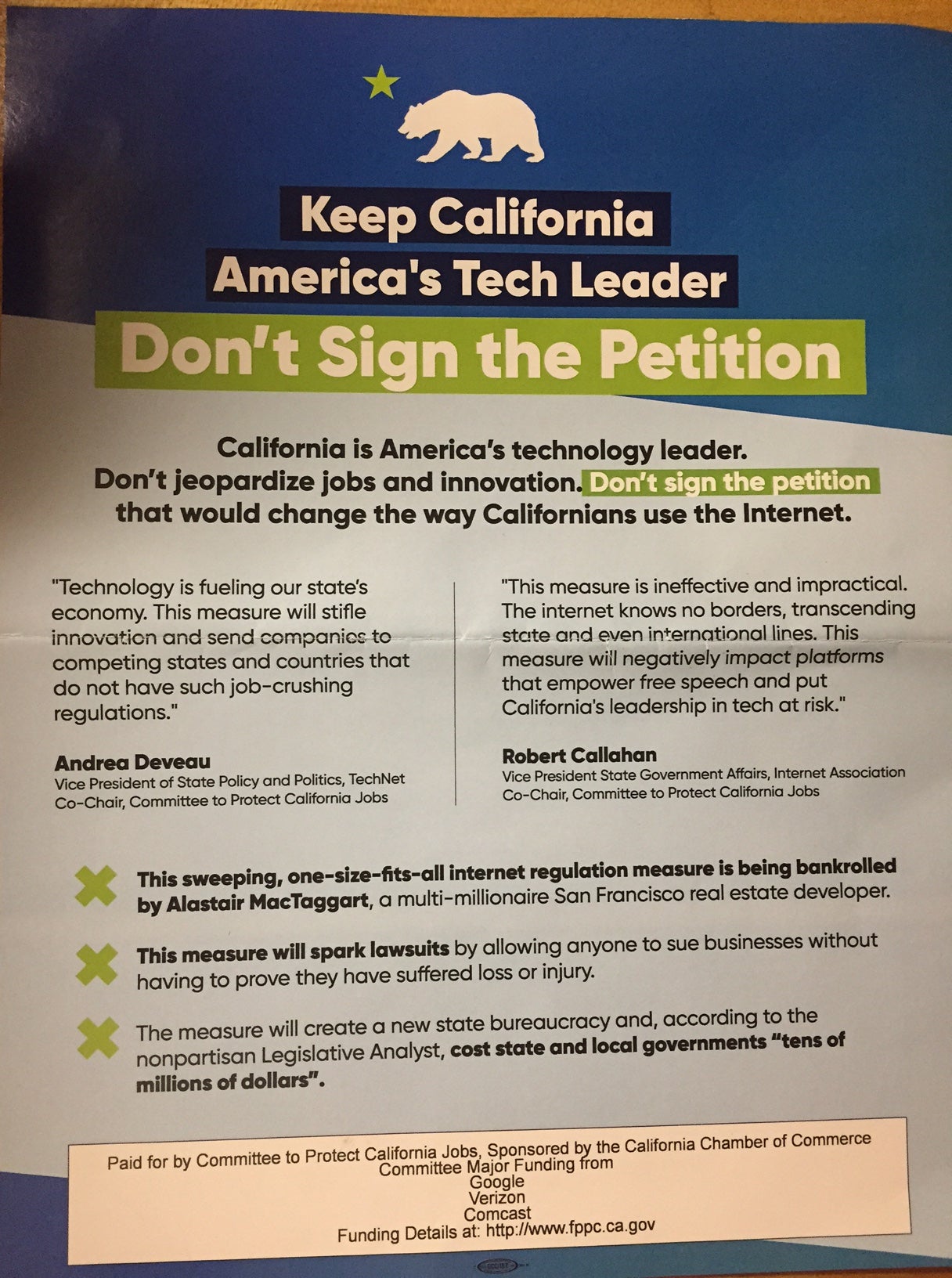

Hardly surprisingly, the tech industry is freaking out. At one event in San Diego where Democrats and progressive activist were discussing the ballot initiative, tech lobbyists came by to distribute hundreds of flyers that aggressively warned that the new initiative would “jeopardize jobs and innovation.” Under the headline “Keep California America’s tech leader,” the flyer said the ballot measure might “spark lawsuits” and hurt California businesses.

A note at the bottom said the flyers were funded by Google, Comcast, and Verizon, yet no flyer peddler in the room wanted to take credit for the effort. When I walked up to a young man who held a few of these flyers in his hand, he said he had nothing to do with it, then promptly left the room.

In the battle ahead, the tech giants and telecoms will probably use more technologically savvy methods to fight the ballot measure. Robin Swanson, a Democratic strategist working on the ballot measure, said she expects tech companies to spend upward of $100 million to fight the initiative.

Why has it taken this long for the party to speak up against the big-tech bullies? The problem is that Silicon Valley also funds a lot of Democrats. Tech companies in the Valley have donated more than $60 million to political campaigns in the past two decades; only the oil and gas industries spend more money on politics. California Democrats’ dependency on Silicon Valley donors is a factor in their timidity toward regulating their businesses, as they risk losing these campaign donations if they start advocating for policies that might limit the power of the tech giants.

With an increasingly well-organized and impatient progressive wing of the Democratic party growing, a fight with big tech seems inevitable.

Is Silicon Valley Democratic or libertarian?

The political ideology of Silicon Valley is often misunderstood: Many on the left dismiss the tech giants as right-wing libertarians who hate the government and want to avoid paying taxes, while conservatives on the right generally see the tech community as ultra-progressive. The truth is more complex.

Mistaking Silicon Valley entrepreneurs for a uniform group of libertarians can be costly. When Republican senator Rand Paul visited San Francisco for a campaign event in 2016, he asked a room full of techies, “Is there anybody here from the leave-me-alone coalition?” He was met with awkward silence, and eventually muttered “… not that many” with an embarrassed smile.

To the contrary, a Stanford University survey of 600 tech entrepreneurs in California revealed that Silicon Valley tech leaders had progressive positions on a whole bunch of issues: They support single-payer health care, environmental regulations, immigration, DACA protections, higher taxes on the wealthy, and paid parental leave.

But there are many crucial issues where Silicon Valley entrepreneurs lean far to the right of California Democrats. These include the power of labor unions and the ideal power balance between government and private enterprise. According to the Stanford survey, 65% of California Democrats say labor unions are good, but only 24% of tech entrepreneurs agree. When asked whether ride-sharing company Uber’s controversial surge pricing policy is fair, 94% of the Silicon Valley techies agreed, but only 42% of Democrats.

Silicon Valley entrepreneurs don’t mind the government regulating other industries, but they prefer Washington to stay out of their own business. Tech companies may vocally embrace single-payer health care, but they are more reluctant to contribute tax revenue to actually fund such a massive investment. Apple famously praised Trump’s massive tax cuts recently. And Amazon is traveling the country looking for new headquarters, asking the cities and state governments competing to give massive tax subsidies to one of the world’s wealthiest corporations.

Democrats’ fight against big tech

In response to heel-dragging such as this, Democrats are leading the party toward a more populist stance against big business, including tech companies. In a time of exploding income inequality, tech monopolies are the perfect targets for an increasingly progressive party. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders certainly think so, with their prominent attacks on tech giants. Hillary Clinton also attacked Uber and the “gig economy” during her campaign for US president.

Congressman Ro Khanna embodies the Democratic party’s general shift to the left. As a representative of a California district that encompasses a big part of Silicon Valley, he strikes a fine balance between embracing the party’s new economic populist message and not alienating the tech world. But he wasn’t always this way.

In 2014, Khanna ran for Congress as a disruptive force in the Democratic party, courting Republican support with a centrist, pro-business message and attacking “tax and spend” liberalism. He was endorsed by a whole bunch of Silicon Valley moguls, including Google’s Eric Schmidt and Sundar Pichai, Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg, and investor Marc Andreessen. Khanna even got a $2,600 check from Peter Thiel, the libertarian Republican megadonor who famously supports Donald Trump.

Khanna lost on his centrist platform in 2014—and then ran again in 2016 as a populist candidate, and won. This time, he refused to take money from corporations or PACs, his economic message sounded more like Elizabeth Warren’s, and he endorsed Bernie Sanders in the Democratic primary. Many skeptical progressives assumed Khanna would reveal himself as a centrist, corporate Democrat after winning the election. Instead, he went further left: He recently co-founded the Antitrust Caucus in the US House of Representatives with a stated goal to “reorient antitrust policy to consider all the factors of economic concentration,” and he has also been a vocal critic of the Amazon-Whole Foods merger, as well as the AT&T-Time Warner merger.

Khanna’s district incorporates Apple’s HQ in Cupertino and most of San José. Even though this area has an annual median household income of more than $111,000, his priorities are mostly with the working class. He has suggested a trillion-dollar expansion of earned-income tax credit for low income families, he’s a vocal supporter of labor unions, and has made massive efforts in education and job training to combat job loss generated by automation.

But Khanna has also been careful not to demonize the tech companies in his own district. In a recent interview, he said tech is “not where the bigger antitrust issues are.” When he attacks tech monopolies, he also seems more comfortable focusing on Amazon, which is conveniently headquartered in Washington state, than the local Valley giants.

Khanna’s careful positioning gives us a glimpse into the national implications of the coming battle between tech companies, the government, and voters. Stronger regulation of big tech is no longer a fringe issue, either: A recent poll shows that public support for tech regulation has spiked, from 40% in November to 55% now. This means Democrats and Republicans alike will need to listen more carefully to their constituents’ views on tech issues instead of being wooed by campaign support funds.

Democrats have a real challenge ahead. They are trying to ride the wave of the big-tech backlash without appearing to hurt the companies who are actually responsible for the backlash.

At some point soon, they may have to choose between their biggest group of voters and their biggest donors.