The strange process of naming extreme weather events

Europeans are currently withstanding the assault of a “Beast From The East.” In January, the northeast US was terrorized by a “Bomb Cyclone” while in 2014 it was a “Polar Vortex.” Almost every winter since 2010 has delivered a “Snowmageddon.” Headline writers and news anchors love giving dramatic names to winter weather, but where did this tradition come from?

Europeans are currently withstanding the assault of a “Beast From The East.” In January, the northeast US was terrorized by a “Bomb Cyclone” while in 2014 it was a “Polar Vortex.” Almost every winter since 2010 has delivered a “Snowmageddon.” Headline writers and news anchors love giving dramatic names to winter weather, but where did this tradition come from?

Europe’s “Beast from the East”—a prolonged period of cold temperatures and snow—is not totally extraordinary, in that you would expect cold temperatures and snow during winter. But it is fair to say that the “beast” doesn’t normally bite this hard: parts of Europe have logged record low temperatures, and it even snowed in Rome.

The event was caused by a split in the polar vortex, the low pressure system that normally sits over the Arctic; it’s happened multiple times over the past few decades, most recently five years ago. We can trace that split back to two tropical cyclones that formed in the Pacific in mid-February and pumped a lot of heat into the upper atmosphere. The heat from these proverbial butterflies interrupted normal weather patterns, destabilizing the polar vortex and causing it to separate into several vortices on Feb. 9th.

One side of the split moved down over Eastern Europe, bringing cold weather with it. That’s the aforementioned “beast.” But at the North Pole itself, temperatures are substantially higher than normal where the colder vortex has been displaced by those warmer cyclones—rising above freezing despite the polar night. Reuters reports that on the northern tip of Greenland, the Cape Morris Jesup meteorological site has had a record-smashing 61 hours of temperatures above freezing so far in 2018. “It’s never been this extreme,” said Ruth Mottram, a climate scientist at the Danish Meteorological Institute. Around the entire Arctic region, temperatures are now about 20°C (36°F) above normal.

But let’s go back and talk about that name—the “Beast from the East.”

Until 2015, different European agencies and individuals had been giving their own names to winter storms, somewhat at random. Popular Irish weather presenter Deric Hartigan picked his own names, for example, while the German media used an unofficial naming regime from the Institute of Meteorology at the Free University in Berlin, which has been christening all high- and low-pressure systems since 1954.

The decision to give winter storms official names in the UK and Ireland was made after the St Jude’s Day storm in October 2013, which caused 17 deaths across Europe. “Not having a single authoritative system,” the Met Office wrote at the time, “was causing confusion, with the media using names from different schemes to describe the same storms.” The agencies were worried, with good reason, that this confusion would make severe weather warnings less effective.

As a side note, the “Beast from the East” mentioned above is related to a high-pressure system, not a low-pressure winter storm—so it doesn’t have an official name. Berlin Free University has named the high pressure area “Fritz” and “Hartmut,” depending on which part of the event you’re referring to. Given that the Met Office is issuing weather warnings for it, perhaps it should be considering naming high pressure systems too.

But 2015 wasn’t the start of this phenomenon. Meteorologists have been officially christening hurricanes, cyclones, and typhoons (which are local names for the same phenomenon) since 1953, when the United States began using female names for hurricanes. The US National Ocean Service says that it was for much the same reason that the UK and Irish Met Offices chose to in 2015—that “confusion and false rumors resulted when storm advisories broadcast from radio stations were mistaken for warnings concerning an entirely different storm located hundreds of miles away.”

The use of solely female names, incredibly, seems to derive from a depressingly sexist joke about hurricanes and women both being hard to predict. It can be traced back to a 1941 novel called Storm, written by George R Stewart, about a junior meteorologist who named Pacific storms after former girlfriends. The novel was popular among US Air Force and Navy meteorologists during World War II, and when a group of them were assigned to forecast tropical cyclones in the Pacific, they decided to name them after their wives. In 1945, the armed forces publicly adopted a list of women’s names for typhoons in the Western Pacific, but they couldn’t persuade the US Weather Bureau to do the same for the Atlantic.

In 1947, the US Air Force Hurricane Office began using the military phonetic alphabet to name North Atlantic storms in internal communications only. The system was made public during the 1950 season, when three simultaneous hurricanes in the North Atlantic caused much confusion. Unfortunately, a new international phonetic alphabet was agreed in 1952, making things even more confusing, so in 1953 the US Weather Bureau finally agreed to use women’s names.

Women, of course, were less than jazzed about this. With the rise of feminist activism came growing criticism of the practice, and in 1970 activist Roxcy Bolton wrote a letter to the National Hurricane Center in Miami, asking them to “cease and desist” from using female names, as it “reflects and creates an extremely derogatory attitude toward women,” who “deeply resent being arbitrarily associated with disaster.”

Bolton also complained about the term “hurricane,” which she argued sounded too much like “her-icane.” She began using the term “him-icane” shortly afterwards. In a second letter, in 1972, she repeated her demands, adding that storms should be named after US Senators, because they “delight in having streets, bridges, buildings” named after them.

In 1972, Bolton visited the National Hurricane Center. The associate director of the National Weather Service, Karl Johanssen, initially scoffed at her demands, but attempted a compromise where men’s names would be used for one year and women’s names in the following year. Bolton didn’t budge, and the system remained the same.

Australia and New Zealand began using both men’s and women’s names in 1975, but it took until 1978 for the US system to be reformed. “Some women suggested that the naming procedure was sexist. I believe that to be true,” said NOAA administrator Richard Frank, and the modern system where male and female names are alternated was put in place. Bolton still didn’t approve, saying that she was not exactly “enthusiastic” about naming tropical cyclones after men or women because of “the negative image it projects.”

Nonetheless, the system stuck, and the first “male” hurricane—Bob—did $20 million of damage to the Gulf Coast in July 1979. The United States has a policy of reusing names for storms—though the names attached to the most deadly and damaging storms are “retired” out of respect. The UK Met Office told me that it doesn’t reuse any names, and nor does it use names retired by other weather services. It also doesn’t change the name of a storm that’s been already named by another weather bureau—which is why the UK was hit by “ex-hurricane Ophelia” in 2017.

The naming convention could well change again in future. In 2014, a team of gender researchers found that* storms with “feminine” names caused significantly more deaths than “masculine-named” ones do. Their study suggests that this is because hurricane names “lead to gender-based expectations about severity and this, in turn, guides respondents’ preparedness to take protective action.” In other words, you’re more likely to take cover if Hurricane Patrick is bearing down on you than you would be if it was Hurricane Patricia. “Our findings highlight the need to reexamine the practice of assigning arbitrary names to natural hazards in an effort to facilitate communication,” the researchers concluded.

* There was some dispute over the study’s methods, which the authors have responded to. The exchange was summarised well by Snopes.

Let’s go back further, because the United States was not the first to give personal names to hurricanes. That honor goes to a man named Clement “Wet” Wragge, the Government Meteorologist for Queensland, Australia, between 1887 and 1907. Tall, thin, and known for his “mop of flaming red hair, explosive temper and the adjectival luxuriance of a bullocky”—someone who drives teams of bullocks—Wragge seems to have been quite the character. He was often found issuing colorful warnings for local mariners in his Special Forecasts for Australasia. For the week ending Oct. 9th, 1902, he wrote:

The Antarctic disturbance Melba, named after the divine songster, will be the ruling factor over the southeastern quadrant of Australasia generally. Vessels bound west through Bass Straits from eastern ports will surely meet Melba and some persons will not only have reason to remember the superb singing of the original but also recollect the howling and the whistling of the winds of her cognomen. The Antarctic disturbance, James, now south of Wellington, will soon have passed into west longitudes.

Wragge, according to a historical note from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, came to the idea slowly. First he used letters of the Greek alphabet: gamma, delta, and so on. Then he started picking names from Polynesian, Greek, and Roman mythology. Then historical figures. Then South Sea Island women’s names (which may have inspired George Stewart’s aforementioned book, Storm). Finally, he began using the names of contemporary politicians he disliked—especially for cyclones which were “causing great distress” or “wandering aimlessly about the Pacific.”

Born in Worcestershire, England, in 1852, his parents died when he was very young, and his grandmother raised him, teaching him the basics of cosmology and meteorology. As an adult he travelled widely, and in 1881—after hearing that the Scottish Meteorological Society wanted to set up a weather station on the UK’s tallest mountain, Ben Nevis—he volunteered to record the data. From June 1st to mid-October, he climbed the mountain daily—setting out at 5am and returning in the evening, covered in snow and ice. The Society awarded him their gold model and his profile rose, enabling him to crowdfund the construction of an observatory on the mountain.

He failed to get the job of superintendent of the observatory, so in 1884, he moved to Australia, setting up a number of weather stations and becoming one of the first people to make forecasts in the territory. His activities caught the attention of local officials, who asked him to build a meteorological service that could help stem shipping losses from cyclones. Wragge did just that, but immediately began raising hackles by issuing forecasts not just for Queensland, but for other parts of the continent too. He would sign these forecasts, “Meteorology of Australasia, Chief Weather Bureau, Brisbane,” and claimed that other weathermen lacked his professionalism and authority—that they were merely astronomers whose time was also filled with postal and telegraph duties.

Nonetheless, Wragge’s achievements began stacking up. He set up a sprawling network of weather stations across Queensland, designed a series of storm signals, set up an international weather service with New Caledonia, and began naming cyclones.

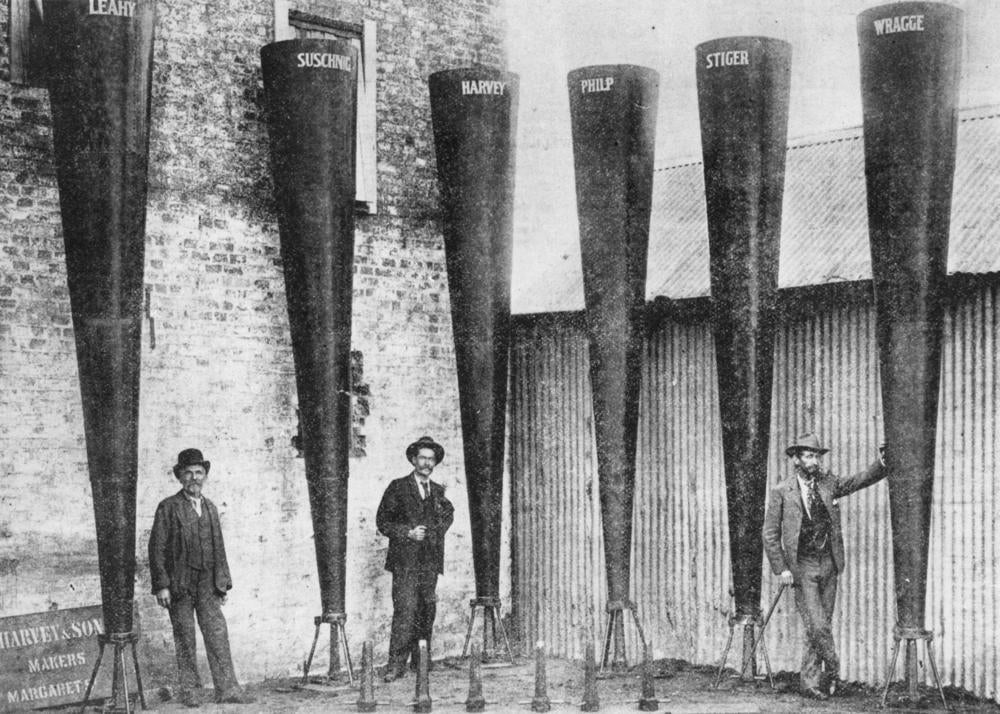

He even experimented with cloud seeding techniques, attempting to break a drought in 1902 by firing a number of specially-designed cannons into the air. The cannons—known as Steiger Vortex Guns—had been deployed across Europe to induce rain before it could turn into hail and damage crops, and Wragge thought they might also work in Australia’s dry climate.

Ten of the cannons were placed around the town of Charleville, about 500 miles (800km) west of Brisbane, and on Sept. 26th they were test fired. Some fruit fell from a wagon after a horse was startled, but that fruit was all that fell to earth—the test was a failure, and Wragge wasn’t even there to see it. He’d been forced to leave town following an argument with the local council. Not long afterward, when his funding was reduced as part of the federation of Australia, he resigned.

After retiring to New Zealand, he developed an interest in the occult, took up yoga, and supposedly converted to Islam before dying in 1922 from a stroke. One account of his later years describes him as “resembling a gaunt mystic, in a garden like a jungle.”

Wragge was likely the first person to give storms human names, but he wasn’t the first to name storms at all. There are records of storms prior to 1860 named after the places where they struck hardest, the saint days on which they arrived, or the most prominent victims.

The Royal Charter Storm of 1859 was named after the Royal Charter ship which was driven onto the east coast of Wales with the loss of 450 lives. 133 other ships sunk, another 90 were badly damaged, and the death toll was estimated at around 800. The following year, the newly-created UK Meteorological Office, under the command of Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy, began issuing its first gale warnings in response.

Another is the Night of the Big Wind—a powerful windstorm that swept across Ireland on Jan. 6, 1839. Hundreds of people died, and a quarter of the buildings in Dublin were damaged, mostly the fragile homes of the poor. In Galway, the Tuam Herald reported, “men, women, and children screaming, crying with raw terror.” The storm immediately entered Irish folklore, and when Ireland introduced the Old Age Pensions Act in 1908, many Irish Catholics had no birth registration. To solve this problem, one of the questions used to determine proof of age was whether the applicant remembered the Night of the Big Wind.

Going back even further, in 1508, Hurricane San Roque, named after the Catholic Saint Roch, hit the newly-discovered territory of Puerto Rico. Spanish conquistador Juan Ponce de Leon, who became the first governor of the island, reported his ship being brought to shore by the high winds and waves.

The earliest-named storm that I could find was the First St Marcellus’ Flood, which swept across Europe around Jan. 16, 1219, drowning 36,000 people along the coast of the Netherlands. A Second St Marcellus’ Flood, on Jan. 16, 1362, was nicknamed “Grote Mandrenke”—Low Saxon for “The Great Drowning of Men.”

The Bible, of course, records 40 days and 40 nights of rain, and ancient cultures from every continent each have their own flood myths, which many modern historians believe could be linked to extreme weather at the end of the last Ice Age.

Before that, the only evidence we have of ancient storms is the marks they left on rocks, coral, and sediment—the study of which is known as paleotempestology. From these records, we’ve found proof of prehistoric tropical cyclones and tsunamis. No doubt the survivors of these ancient storms and floods gave them names—perhaps even a historical equivalent of the “Beast from the East.” But we’ll never know—they’ve been swept away by the time.

This article was originally published on How We Get To Next, under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license. Read more about republishing How We Get To Next articles. Sign up to the How We Get To Next newsletter here.