A new scientific theory suggests the moon formed from a cosmic vapor donut

Before this week, there were three main theories for how the moon formed:

Before this week, there were three main theories for how the moon formed:

- The giant-impact hypothesis, most popular within the scientific community, which suggests that a giant Mars-sized body violently collided into a still-molten Earth and caused a piece of molten rock and metal to break off.

- The co-formation theory, which theorizes that the Earth and moon formed at the same time from the same molten, gaseous blob.

- The capture theory, which proposes that the Earth pulled a random body into its gravitational orbit while the interstellar object was whizzing by.

Now scientists from the University of California, Davis and Harvard are suggesting a fourth model of formation. The theory, published Feb. 28 in the Journal of Geophysical Research–Planets, resolves several problems presented in the other three.

The role of a synestia in forming the moon

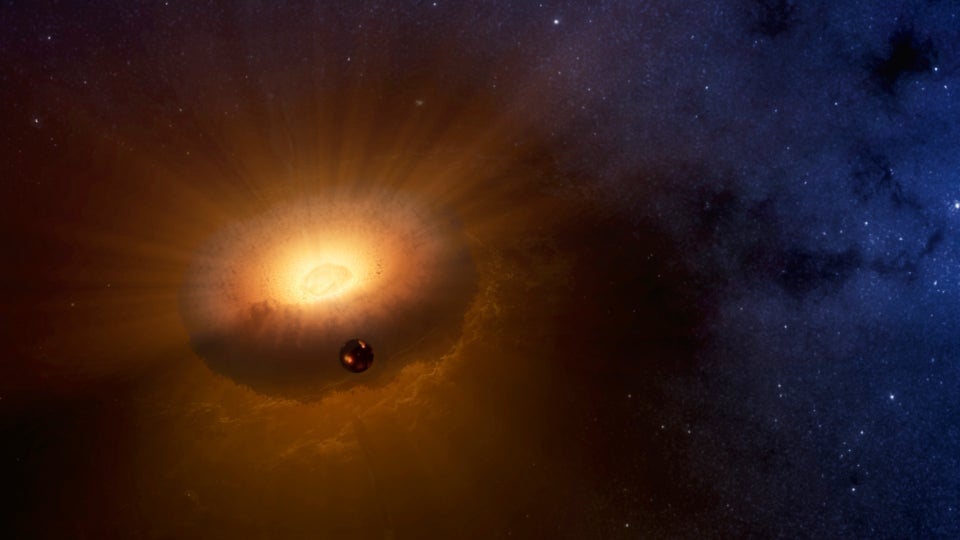

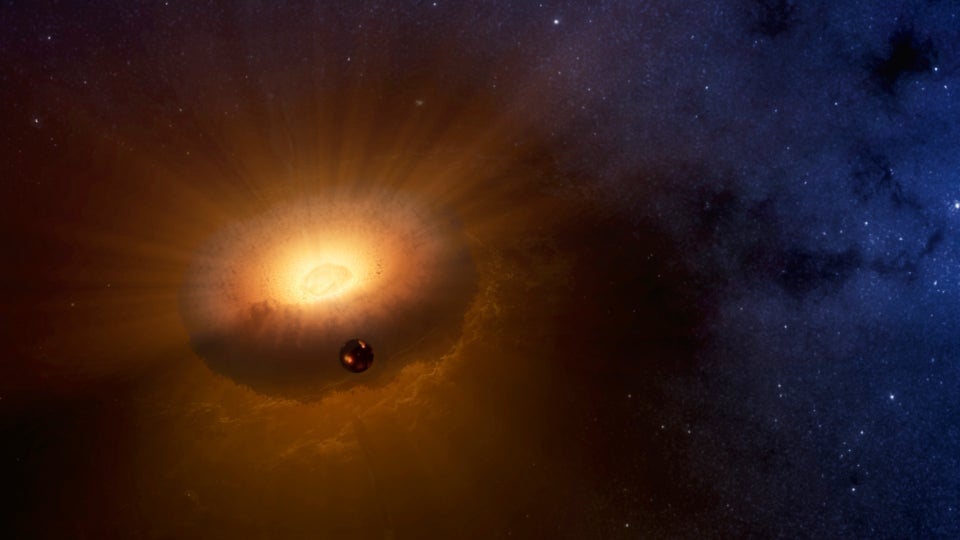

It suggests that the moon emerged from a planetary object called a synestia, a rapidly spinning, donut-shaped mass of molten and vaporized rock. Synestias, proposed as an object category in 2017 by two of the paper’s authors, form after collisions between planet-sized objects and collapse over hundreds of years into molten planets as they lose their heat.

When the Earth-synestia formed, the researchers posit, its parent collision injected chunks of rock into its orbit, pieces that became seeds for the birth of the moon. As the synestia collapsed over time, mass also condensed around those chunks until they separated from the rest of vapor donut, becoming an entity of its own.

What this new theory would solve

The theory would explain why the moon’s composition is a subset of the Earth’s. The high temperatures—some 4,000 to 6,000 degrees Fahrenheit—at which the moon formed vaporized certain elements while keeping intact others. The model also has more flexibility than prior theories because there are multiple ways in which the Earth-synestia could have formed.

“The new work explains features of the moon that are hard to resolve with current ideas,” said Sarah Stewart, professor of earth and planetary sciences at UC Davis. “This is the first model that can match the pattern of the moon’s composition.”