“Separate and unequal:” 50 years later, a landmark report on US racial inequality still resonates

“Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.”

“Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.”

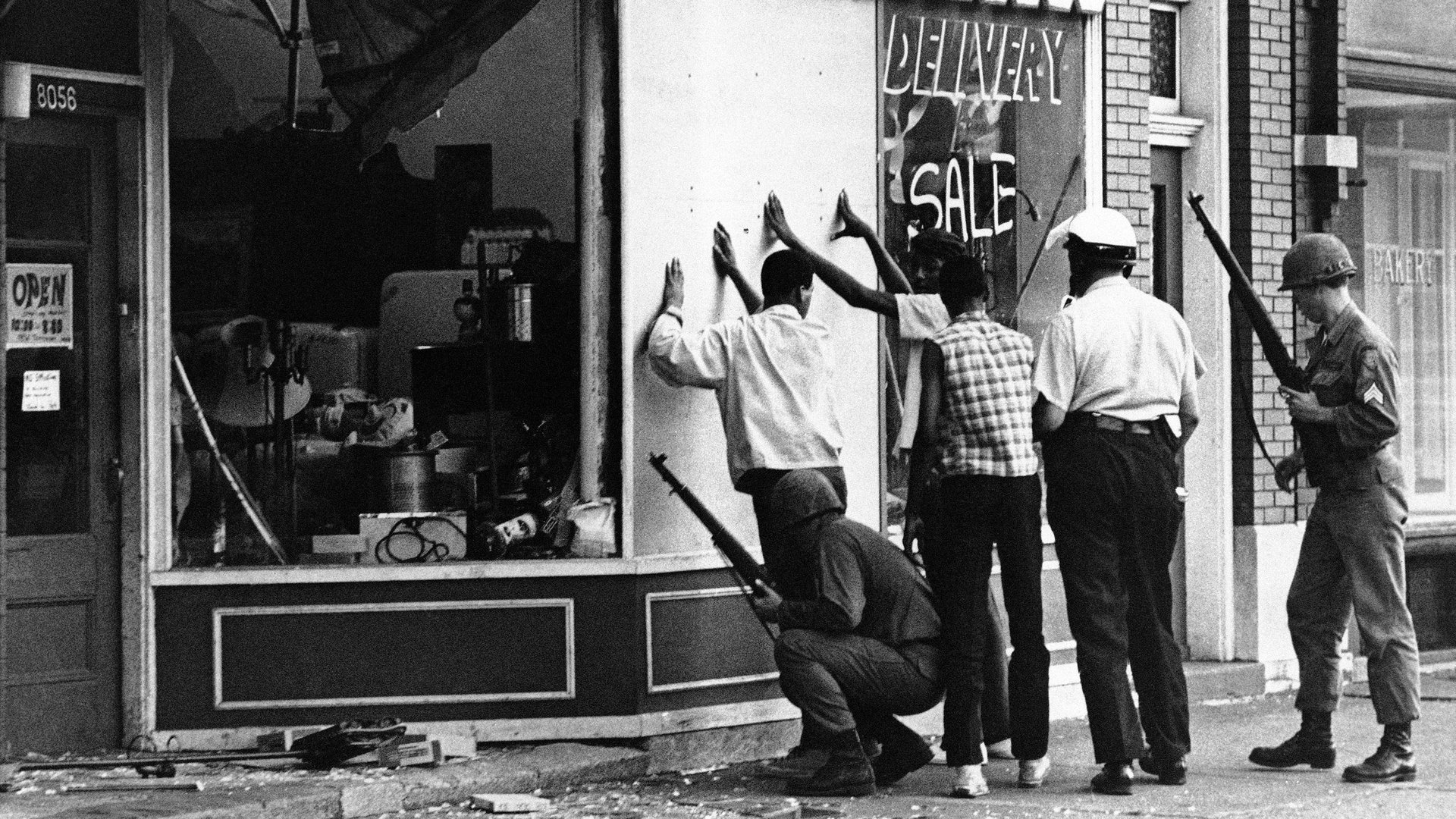

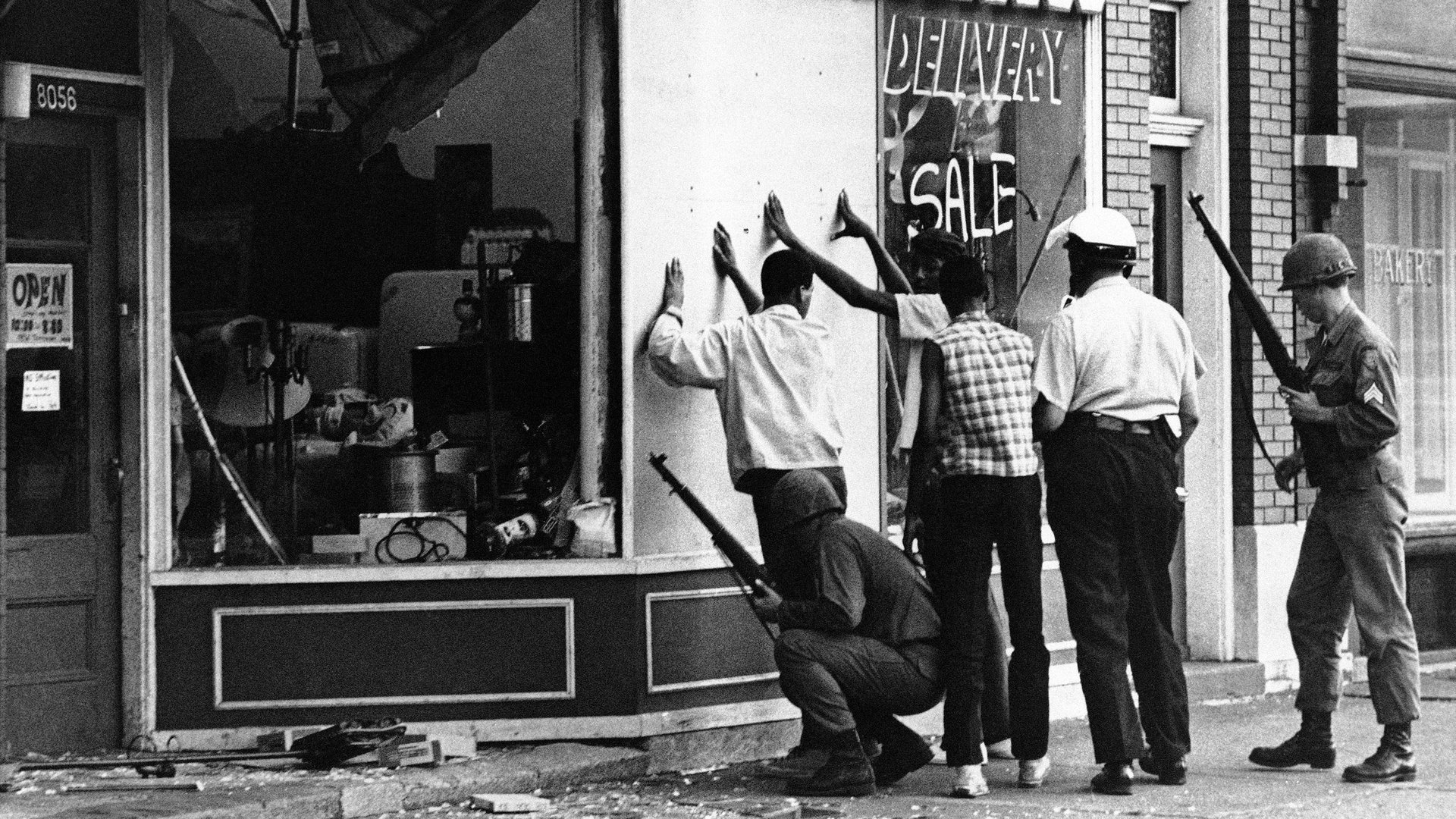

This was the main conclusion of the US National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders in a scathing 1968 report (pdf). In the summer of 1967, president Lyndon Johnson convened an 11-member committee to investigate the race riots and disorder that broke out in Detroit, Newark, and scores of other American cities that year. The commission was charged with explaining what happened, why it happened, and what could be done to stop it from happening again.

The Kerner report, as it became known after committee chair Otto Kerner, then the governor of Illinois, was unsparing. The politicians, industry leaders, and law enforcement officials who compiled the report laid the blame on white racism. In the report’s summary, the committee wrote:

Segregation and poverty have created in the racial ghetto a destructive environment totally unknown to most white Americans.What white Americans have never fully understood but what the Negro can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.

The commission went on to highlight “pervasive discrimination and segregation” in housing, education, and employment. Persistent racial prejudice threatened America’s future, it warned.

Now, 50 years later, many of the report’s findings are still frighteningly applicable, from the lack of economic opportunities for black people to housing segregation to concerns about “mass destruction weapons” used by police departments. A new report by former senator Fred Harris (the only living member of the committee) and Alan Curtis, CEO of the Eisenhower Foundation, finds the US has in fact regressed in many aspects of race and poverty since 1968.

The Kerner commission said racial inequality needed to be addressed with sweeping federal action and spending, calling for “a commitment to national action on an unprecedented scale.” The government would need to, among other things, invest in housing, create 2 million jobs, and provide job training programs. The commission also suggested reviews of police operations and the recruitment of more black people to police forces. “There can be no higher priority for national action and no higher claim on the nation’s conscience,” the report said.

Instead, when the report was released on Feb. 29, 1968, Johnson rejected it and didn’t act on the recommendations. Later that year, both Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated. Still, in his new report, Harris says that for about a decade after the commission’s report progress was made on reducing racial economic inequality. But since then, “burgeoning globalization, increasing automation, conservative political change, and eventually, unfriendly Supreme Court decisions” stopped, or even reversed, the progress.

Not every aspect of black American life is as bad as it was half a century ago, but the improvements shouldn’t be overstated. There is more widespread participation in politics and access to education has increased. But disparities in employment, wealth, and incomes have stayed the same or deteriorated. Today, “America is a country more divided, with less economic opportunity,” wrote Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz in his section of the new report (pdf).

According to the Economic Policy Institute, the main area of improvement is in education. Data from the National Center for Education Statistics show that 92.3% of young black people (aged 25 to 29) at least completed high school in 2017, effectively closing the gap with white people of the same age (92.5%). In 1968, just 54.4% of young black people finished high school, compared with 75% for whites, according to the EPI.

Still, white people are twice as likely to have a college degree today. The university gap has stayed the same over the past 50 years, with college attainment doubling for both groups. This has led to absolute gains for black Americans’ income and wealth, although inequality remains significant.

Income inequality

Median income for black households increased by 43% over the past 50 years, faster than income growth for white Americans, according to the EPI. However, the income gap remains wide.

Wealth inequality

The same is true for wealth. In the early 1960s, black people had little net wealth, something in the region of $2,000. That has increased to more than $17,000 recently, but white Americans’ wealth is 10 times higher, at $171,000, according to the latest data from the Federal Reserve.

Employment inequality

The Kerner report said in 1968: “Despite continuing economic growth and declining national unemployment rates, the unemployment rate for Negroes in 1967 was more than double that for whites.” That statement is as true today as it was then.

Homeownership inequality

The gap between white and black households has worsened when it comes to homeownership, which contributes significantly to the wealth inequality gap. In the last quarter of 2017, the black homeownership rate was 42.1%, compared with 72.7% for non-Hispanic white people, according to Census data (pdf). For black households, the homeownership rate is virtually unchanged from 50 years ago.

For a while, homeownership rates were rising for black people. These gains were reversed by the 2008 financial crisis after banks, such as Wells Fargo, deliberately pushed unfavorable mortgages on black communities. When the subprime bubble burst, black Americans disproportionally suffered.

Mass incarceration

Undoubtably, one of the most significant manifestations of racial inequality relates to incarceration. The share of black Americans in prison or jail almost tripled between 1968 and 2016—from 604 of every 100,000 in the total population to 1,730 per 100,000—and is currently more than six times the white incarceration rate. “In 1968, African Americans were about 5.4 times as likely as whites to be in prison or jail. Today, African Americans are 6.4 times as likely as whites to be incarcerated,” the EPI said in a recent report.

Despite the attention generated by the 1968 Kerner commission report—it sold two million copies—many of its findings are as true today as they were back then, and in some cases have gotten even worse. “Poor health and sanitation conditions in the ghetto result in higher mortality rates, a higher incidence of major diseases, and lower availability and utilization of medical services,” the report said of poor black urban communities in the 1960s. Last month, a report by the Environmental Protection Agency found that people of color are much more likely to live near polluters and breathe polluted air, putting them at greater risk of health problems.

“We support integration as the priority education strategy; it is essential to the future of American society,” the 1968 report concluded. But data increasingly show that school segregation is getting worse.

The report also condemned “moves to equip police departments with mass destruction weapons, such as automatic rifles, machine guns and tanks. Weapons which are designed to destroy, not to control, have no place in densely populated urban communities.” This call, too, has largely been ignored, and with dire consequences in Ferguson, Missouri, where police, armed with military equipment, clashed with protestors after the shooting of black teenager Michael Brown in 2014.

Harris, now 87, says the new report revisiting the Kerner commission’s findings is a call for action. But so was the 1968 report, which concluded:

We have uncovered no startling truths, no unique insights, no simple solutions. The destruction and the bitterness of racial disorder, the harsh polemics of black revolt and white repression have been seen and heard before in this country. It is time now to end the destruction and the violence, not only in the streets of the ghetto but in the lives of people.