Harley Davidson’s 100-year history is a case study in the marketing of the American maverick

The Harley-Davidson motorcycle is quintessentially American. It embodies rugged individualism, an outlaw spirit, and noise-polluting machismo. To hear a hog’s signature snarl before catching its blinding chrome in the rearview mirror is to be reminded of America’s odd fondness for causeless rebels and brutish anti-heroes.

The Harley-Davidson motorcycle is quintessentially American. It embodies rugged individualism, an outlaw spirit, and noise-polluting machismo. To hear a hog’s signature snarl before catching its blinding chrome in the rearview mirror is to be reminded of America’s odd fondness for causeless rebels and brutish anti-heroes.

These are qualities, probably not coincidentally, that a plurality of Americans celebrated when they voted for Donald Trump as their president. And so it’s no surprise that the European Union is considering retaliating against Harley-Davidson in response to Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs. If you want to hit the US with a highly symbolic trade war threat, you’d be hard-pressed to find a better target.

But Harley-Davidson is important for reasons that go beyond its status as an icon of American exceptionalism. The fact that, of the scores of American motorcycle companies that started around in the early 1900s, only Harley-Davidson remains is an accident of circumstance and serendipity—involving America’s path toward industrialization, two World Wars, the Great Depression, Hollywood, and even a few trade wars. Its history offers a lens through which to understand the vicissitudes of American manufacturing and social change—the forces that once made America great, and now bring it to the brink of warring with its trade partners.

Harley-Davidson in America’s Machine Age

William S. Harley and Arthur Davidson were born on the crest of the Machine Age wave in the late 1800s. The two grew up next-door to each other in the industrial hub of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, both of them sons of immigrants. While in their early 20s, the childhood chums began tinkering with an engine for a motorized bicycle. They worked in a 10-by-15-foot shed in the Harley family’s backyard, the words “Harley-Davidson Motor Company” scrawled on its door.

By 1903, they had completed their first racer model. Within three years, they opened their first factory and issued their first motorcycle catalogue.

The uneven pace of America’s modernization helped shaped the physical features that set Harley-Davidsons apart. Outside of East Coast metropolises, people couldn’t rely on trains and streetcars exclusively for transport. Horses were expensive, inconvenient, and took up a lot of space. Cars were out of reach for all but the richest Americans—and anyway, both bicycles and cars worked better on paved roads, which, as economist Robert Gordon explains in The Rise and Fall of American Growth, much of America still lacked.

Harley-Davidson motorcycles offered a solution for backroads America. The toughness of its engine and frame made the bikes well-suited to an era in which people needed to travel rough roads and long distances, while its heavy-duty design set it apart from comparatively svelte and speedy European motorcycles.

The brand soon gained a reputation for endurance. In 1908, Walter Davidson, Arthur’s brother, won a perfect score riding their motorcycle in the 7th Annual Federation of American Motorcyclists Endurance and Reliability Contest. They could climb steep hills with ease and cruise for hundreds of miles. Harley-Davidson’s reputation spread, and orders surged. That year, the company delivered its first orders to a police force—a customer base that continues still today.

The brand also targeted rural customers from the get-go, with early ads boasting that machines were favored by Indiana farmers in part because the quietness of their engine wouldn’t disturb horses, Margie Siegal notes in Harley Davidson: A History of the World’s Most Famous Motorcycle. Harley and Davidson even nicknamed their motorcycle the “Silent Grey Fellow”—not exactly what the motorcycle is known in the present. (In fact, in the 1990s, the company tried in vain to patent its engine’s piercing growl.)

The power and size of the Harley made it appeal to both militaries and businesses. In 1912, the company began exporting motorcycles to Japan’s military. It also sold vehicles to US Army for its incursion into Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa, the revolutionary leader. Meanwhile, in the early decades of the 1900s, Harley sold a big share of its motorcycles to entrepreneurs, the bikes kitted out with hutches on the back for ferrying everything from bread and milk to dye or candy.

Riding just for fun

The revolution of cheap Model T Fords beginning in 1908 ate into the motorcycle market. And so Harley began promoting a new rationale for motorcycle ownership: leisure. Harley invested in building clubs for owners of its vehicles, so that fellow motorcyclists could use their wheels not just for commuting but for group joyrides.

Not only did the Harley groups thrive in the easy-money years of the 1920s, they also helped the company survive the Great Depression. When the depression hit in the 1930s, sales dropped so precipitously that Harley-Davidson laid off workers. The company relied in large part on sales to Japan—including its military—to stay afloat.

But however bad the Great Depression was for Harley-Davidson, it was oddly good for motorcycling as a social institution. The cratered economy made gas cheap, and left unemployed people with nothing to do. Motorcycle clubs filled the void, creating a network of groups across America that would become even more popular after the war ended.

By the time the US entered World War II, Harley was among only two US motorcycle companies still standing (the other was Harley’s archrival, Indian). Both companies bounced back fast once the US entered World War II, working overtime filling orders for America and its allies.

The accidental rise of the American rebel

The widespread use of Harleys among American armed forces during World War II had the benefit of converting thousands of potential customers. When the war ended, returned GIs bought their own.

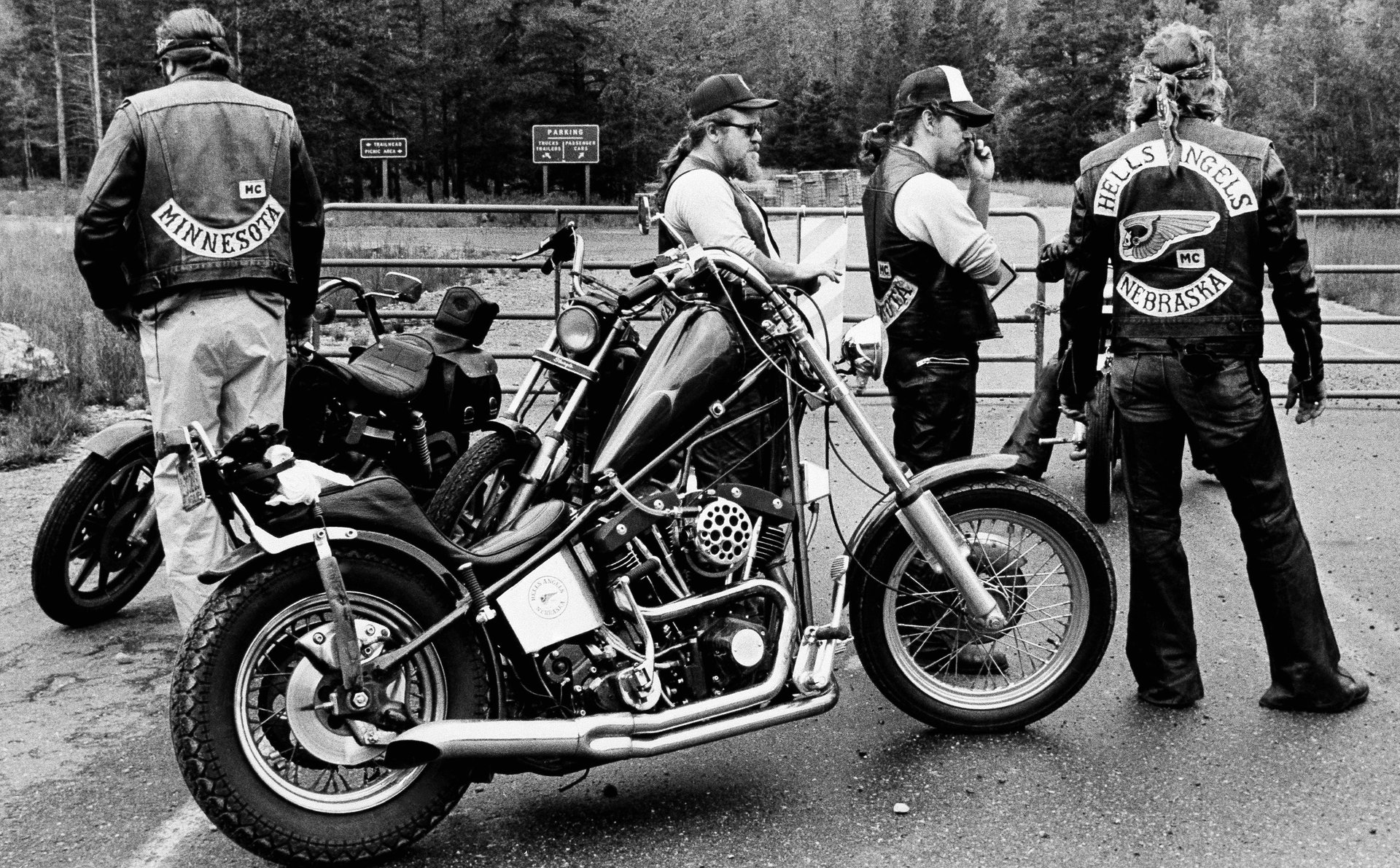

Some vets embraced motorcycles out of a desire to inject a bit more thrill into humdrum civilian life, according to William L. Dulaney, an anthropologist specializing in outlaw motorcycle culture, in his paper, “A Brief History of ‘Outlaw’ Motorcycle Clubs.” Biker clubs also offered the familiar camaraderie of soldier life, providing a sense of community that was vital for vets struggling to reintegrate into society. Some of these groups earned a reputation for blowing off steam the way they had during the war—by boozing, carousing, and revving their noisy Harleys. With war-scarred vets struggling to hold down regular jobs, a few groups of Harley fans also became involved in criminal activity.

In July 1947, the tiny town of Hollister, California, held its annual motorcycle race. Thousands of bikers descended on Hollister, nearly doubling the population and igniting a motorcycle-themed bacchanal that turned occasionally violent. During the raging, booze-soaked party that ensued, a photographer for Life magazine captured an iconic image: a soused man double-fisting beer bottles astride a Harley, surrounded by a carpet of smashed beer bottles. “Cyclist’s Holiday: He and friends terrorize a town,” read the accompanying story’s headline.

The photo was likely staged, and the media exaggerated the mayhem. The official motorcyclists association, which had long sponsored races and rallies like the one in Hollister, reportedly declared that only “one percent” of motorcyclists partook of such deviant behavior, while the rest were good citizens. (The group now disputes having coined that term, but the name stuck; to this day, the term “one percenter” refers to outlaw gangs.)

But the Hollister photo helped the image of the anti-social, miscreant Harley rider take root in America’s popular imagination. The 1953 film The Wild One, starring Marlon Brando as a violent motorcycle gang leader, was loosely based on the Hollister “riots.” Hunter S. Thompson’s 1966 book, Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs, pumped even more dramatic life into the mythos of an emerging Harley culture supposedly menacing America—as did Easy Rider in 1969, starring Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda as drug dealers storming the blacktop on hogs, in search of an alternative American dream.

The lurid tales of biker hellraising weren’t good for Harley. Throughout the 1950s, the company supplemented its core business withs subcontract work for General Motors, according to Siegal.

But motorcycles still had plenty of potential in America. As the swinging sixties dawned, demand for zippy European-style bikes picked up. With its reputation woes, Harley couldn’t seize that opportunity. But across the Pacific, another company saw exactly how it could.

Motorcycling for nice people

Honda made its first motorcycle in 1949. By 1955, it had quietly become the planet’s top producer and, by the end of that decade, was plotting a US invasion that would inspire business school case studies for decades to come.

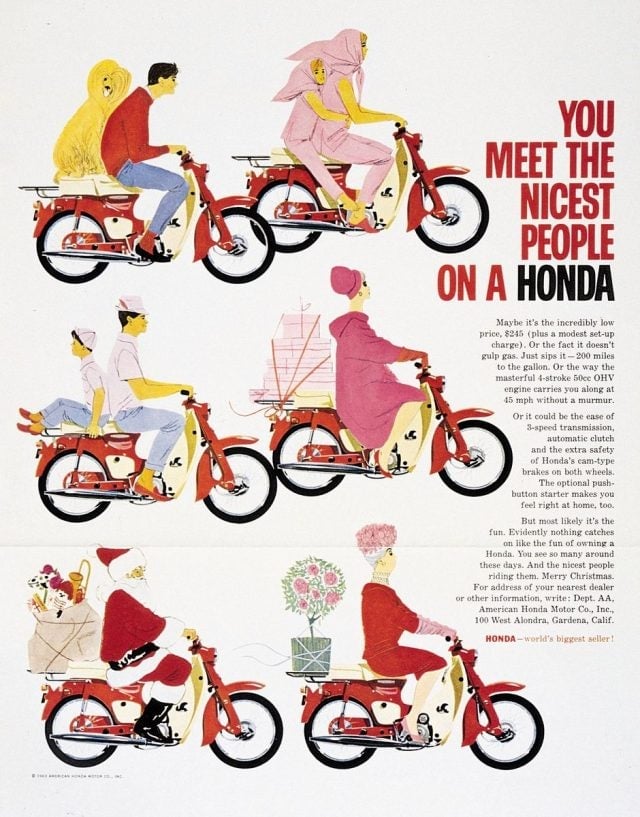

To understand how Honda differentiated itself from its American competitor, one need look no further than a two-page ad in the June 14, 1963 issue of Life magazine. Zipping across the spread were 10 people on motorcycles. It would be hard to come up with a cast that looked less like Marlon Brando: A Ken doll-clone surfer and a trendy young woman in chunky glasses. A pair of society ladies in pearls, updos and lots of pink. Father and son in matching slip-ons. Sunny, clean-cut suburbanites toting schoolbooks, tennis rackets, children, and pet Afghans. Nary a scrap of black leather in sight.

The bike they rode, the Honda 50, was a cheery cherry-red. The tagline said it all: “You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda.”

The ad, conceived by Grey Advertising, was so strong that Honda stuck with it for more than a decade, making it one of the most famous campaigns ever, according to Jeffrey Rothfelder’s Driving Honda. Ads ran in family-friendly publications and even during the Academy Awards, making Honda the first foreign company—to say nothing of motorcycle company—to sponsor the event, in 1964.

Honda got plenty of free publicity, too. That same year, the Beach Boys put out “Little Honda,” their paean to the Honda 50 (known outside the US as the Super Cub). “It’s not a big motorcycle/Just a groovy little motorcycle/It’s more fun than a barrel of monkeys,” sang Mike Love over a chipper guitar line. A version of the song covered by the surf-rock band The Hondells reached #9 on the Billboard 100 chart.

Honda sales exploded, blowing past 500,000 in 1970, up from 40,000 in 1962—and just 1,700 in 1959. As the 1960s wore on, the Japanese invasion intensified. On the heels of its Honda 50, Honda rolled out new lines of small but speedy bikes for more serious motorcyclists. Yamaha and Kawasaki soon followed.

Grey’s ad deliberately portrayed Honda as a foil to Harley-Davidson’s anti-social image. Harley-Davidson tried to shake this reputation in part by making an earnest bid for nice people. In the early 1960s, it unveiled Harley’s first and only scooter—a bike that might have been the lovechild of a Vespa and a toaster. The “Topper,” as it was known, was a commercial dud, its sole claim to fame its service as the Milwaukee Brewers’ bullpen buggy between 1959 and 1995. Harley also invested in an Italian motorcycle company that made sporty, chic, lightweight bikes under the Harley aegis.

Let Harley be Harley

Ironically, Honda’s “Nicest People” campaign actually helped Harley by increasing the American public’s overall interest in motorcycles, says Siegal. High gas prices caused by the oil crisis of the early 1970s boosted demand for energy-efficient transport even more.

It was during the 1970s that Willie G. Davidson—a grandson of the founder, and the company’s chief motorcycle designer—had a crucial epiphany. Willie G, as he’s known, looked the part of a Harley owner, with a bushy beard and a penchant for black leather, and socialized at motorcycle club rallies. He realized that the company’s accidental antihero image wasn’t a problem. It actually worked in its favor.

The vast majority of Harley-Davidson owners weren’t outlaws at all. But they sure got a kick out of feeling like they were. People who might be dentists or accountants by weekday donned leader, polished their chrome, and found community at hog rallies on the weekends. Individuality was also a key part of this subculture. Members of motorcycle clubs poured time and expertise into souping up their bikes and turning them into “choppers,” meaning, a motorcycle modified to have its own distinctive look and feel.

The company began experimenting with these ideas, playing to themes dear to Harley riders, like patriotism. For America’s bicentennial in 1976, the company released the “Liberty Edition,” the Statue of Liberty emblazoned in black on the tank over the words “Born Free.” The company could also take its rebel image too far—as with its release of a Confederate-themed motorcycle in 1977.

Willie G’s focus on designing for the motorcycle subculture was even more important than the themes Harley was trying out. For instance, in 1982, the company debuted the now-iconic FXR Super Glide II—the model Bruce Willis rides in Pulp Fiction, in 1994. The bike was designed to look customized, like something a one percenter might own. (Think of Willis’ famous line, “It’s not a motorcycle, baby, it’s a chopper.”)

Protecting Harley, protecting America

As the Liberty Edition suggested, nationalism was becoming a growing part of Harley’s brand. This intensified as Harley-Davidson’s business struggled against the Japanese competition.

A company called American Machine and Foundry had purchased Harley in 1969. The new owner was a big believer in “scientific management,” focusing on streamlining mass production to boost volume and largely neglecting quality. AMF’s practices roiled labor discontent among Harley workers. The bikes made in this era were sometimes dubbed “Hardly Ableson.”

In 1981, Davidson and other members of Harley’s executive management took the company back from AMF in a leveraged buyout deal underwitten by Citicorp. The rationale was sound. Despite AMF’s cost cuts, Japanese motorcycle makers were still producing better bikes for cheaper. ”We were being wiped out by the Japanese because they were better managers,” the new CEO, Vaughn Beals, told Fortune. “It wasn’t robotics, or culture, or morning calisthenics and company songs—it was professional managers who understood their business and paid attention to detail.'”

The new plan was to concentrate on worker involvement, decentralize quality decisions, and intensify communication about quality on the assembly line—the latter based on Toyota’s inventory control program. But the timing was crummy. A recession hit, dragging on demand. Yamaha and Honda responded by flooding the American market with their extra inventory, pushing down prices.

At last, the US government stepped in. Since the early 1970s, John Davidson, grandson of the founder and president of the company, had been accusing Japanese motorcycle makers of dumping (meaning, selling a good for cheaper abroad than at home). In 1982, the company finally took action—winning an anti-dumping judgment that led then-US president Ronald Reagan to slap tariffs on Harley’s Japanese competitors.

An American rebel goes mainstream

The tariff protection bought Harley-Davidson time to push its new strategy, embracing its edgy hellraiser image full-on. A big part of that effort involved reviving upgraded versions of classic models. “I loved the idea because it gave us a way to attract new customers and screw the Japanese because they didn’t have anything like it in their heritage to go back to,” Vaughn Beals, the new CEO, said in the 1980s, according to Harley-Davidson: The Complete History, by Darwin Holmstrom.

The tariffs helped boost market share and profit. By 1984, business was reviving, but Citicorp’s feet were getting cold. Fearing the end of the tariffs in 1988 would douse that growth, the bank pulled back on its loan advances.

Just as the company was beginning bankruptcy proceedings, a Harley-riding financier swooped in to save it. An IPO—Harley’s second—followed, in 1986. With business improving, in 1987, the company asked Reagan to lift the tariffs. The US president announced the end of the tariffs during a visit to Harley’s factory in York, Pennsylvania. “Harley-Davidson has shown… American workers don’t need to hide from anyone,” said Reagan, drawing wild cheers from Harley workers. A moment later, the president warned that broader, more systematic protectionist policy “invites, even encourages, trade wars.” The crowd stayed mum

By the late 1980s, the company was thriving again, thanks in no small part to its focus on iconic old-school designs like the 1991 Sturgis remake. Another hit was its 1990 Silver Fatboy. The massive, low-slung bike swiftly became the epitome of cool in the popular imagination, summed up by its cameo as Arnold Schwarzenegger’s ride in Terminator 2: Judgment Day in 1991.

The popular lore surrounding the Fatboy also spoke to the undercurrent of nationalism—and specifically anti-Japanese bias—in Harley’s evolving reputation. Rumor has it that the moniker combines the names of “Fatman” and “Little Boy,” the two atomic bombs dropped on Nagasaki and Hirsohima during World War II. The bike’s distinctive yellow rings mimicked the designs of the bombs, while its gunmetal gray paint resembled the B-29 Superfortress bombers that unloaded them. (The company denies the connection.)

Harley’s bad-boy image had commercial potential beyond just motorcycles, the company realized. In the mid-1980s, Harley began a licensing frenzy, selling its logo rights to basketball sneakers, cigarettes, ties, perfume, and beer, according to Harley-Davidson: The Complete History, by Darwin Holmstrom. The beer lines included popular tough-guy brands like Pabst and Miller.

Nicer people than you might guess

In a parallel—and much more significant—marketing effort, the company established its own riding club, the Harley Owners Group (a.k.a. HOG, naturally) in 1983. The club proved popular, with membership numbering 100,000 by the end of the 1980s.

To outsiders, a swarm of HOG members is probably indistinguishable from outlaw biker gangs. But HOG chapters have been careful to differentiate themselves in the community, most notably by focusing on charity work, notes Siegal in her history of the company. “The concept—a social organization based on a specific brand of motorcycle, which offered its members community, an opportunity to participate in charity events, pride in America, and an identity—was extremely successful,” she writes. “There are now more than 1,400 HOG clubs around the world and HOG has been studied by marketers as the most successful community building effort ever engaged in by a company.”

This corporate orientation wasn’t exactly new. It was the first motorcycle manufacturer to grant an African-American dealership rights, in the 1920s. One of the hog-riding motorcycle stars of the 1930s and 1940s was African-American woman Bessie Stringfield. Indeed, despite the macho stereotype associated with Harleys, women have always been a part of the subculture. The HOG social movement was built on service to the community—cementing the identity of a hellraiser who helps others.

And though it has traded in some of the uglier tropes of American patriotism, the company has, since its earliest days, understood the gains to be made in winning global customers. Sales in Japan and Australia helped it emerge as one of the few survivors of the rough early decades of the 20th century. Even as Japanese motorcycles were gobbling up Harley’s US market share in the mid-1980s, booming hog sales in Japan helped power the company’s comeback. It now has factories in Manaus, India, and Australia. In 2017, Harley sold nearly 40% of its motorcycles overseas (pdf). In this, Harley marketing coup pulled off the nifty trick of embracing an anti-establishment, outcast persona through a business built on openness and inclusion.

Harley and Trump

It’s no surprise that Trump counted Harley-Davidson enthusiasts among his most fervid supporters during the 2016 presidential election. The similarities between Trump and the brand are striking—both have built a cult following and business empire around surnames.

Both have triumphed over considerable odds by tapping into America’s enthusiasm for rebels—people who disdain civility and scorn the law. Their improbable popularity comes from packaging cultural nostalgia into an identity, offering community to those who struggle to see themselves in the American mainstream.

The mythology of the American maverick is potent stuff. But as Harley learned, mustering that force matters little without the technical expertise, managerial skill, and long-term vision needed to fashion it into something people value. That investment and discipline saved Harley-Davidson from staying Hardly Ableson. Unfortunately for America—and possibly, the rest of the world—Trump has yet to learn the difference.