A 500-year-old bank in Italy is teetering, and threatens to take the rest of the country’s financial system with it

Uniquely among the euro zone’s beleaguered “periphery”, Italy’s response to the financial crisis has not included nationalizing large parts of its banking system. Compared with the wreckage in Cyprus, Ireland, Portugal and Spain, Italian lenders have gotten off relatively lightly.

Uniquely among the euro zone’s beleaguered “periphery”, Italy’s response to the financial crisis has not included nationalizing large parts of its banking system. Compared with the wreckage in Cyprus, Ireland, Portugal and Spain, Italian lenders have gotten off relatively lightly.

Until now. The finance ministry has announced a revised rescue plan (link in Italian) for the country’s third-largest bank, Monte dei Paschi di Siena. The bank, which traces its roots back to 1472, was propped up with €4.1 billion ($5.4 billion) in government loans earlier this year. The blessing of the European Commission is necessary for it to keep this aid, and Brussels wants tougher conditions attached. If the bank cannot meet these conditions, the loan will convert into shares and the fragile, debt-ridden Italian government will become the proud owner of a bank that has reported more than €8 billion in losses since 2011. At that point, the state of the Italian banking industry as a whole might turn from chronic to acute.

Years of mismanagement and, recently, alleged fraud pushed Monte dei Paschi to the brink. It is already in the midst of cutting 4,600 jobs and closing 400 branches to save costs. The European Commission now wants it to raise €2.5 billion in fresh capital, roughly the same as its current market capitalization and more than twice what the bank had originally planned. It will take aggressive financial engineering—possibly a “bail-in” of private bondholders—to avoid a partial or full nationalization.

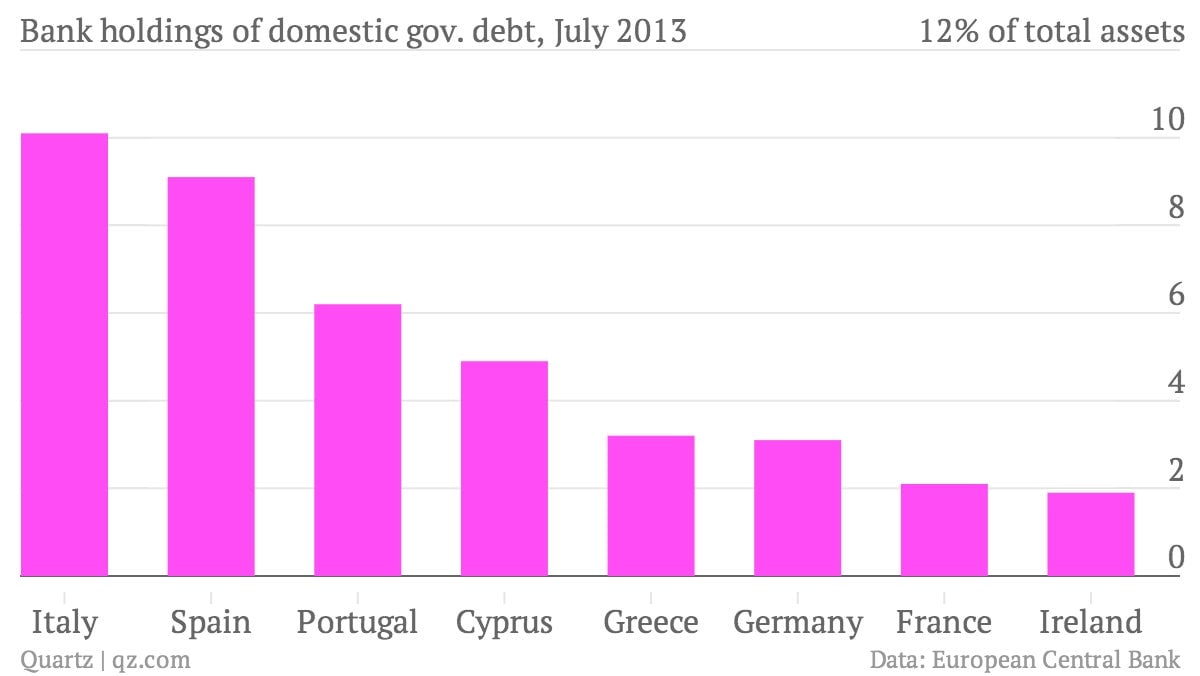

In addition to the steeper capital hike, the commission is keen for Monte dei Paschi to cut down the size of its €29 billion portfolio of Italian government bonds. Italian banks hold huge amounts of government debt—a big reason why the government doesn’t want to nationalize them, since it wouldn’t then be able to borrow from them.

Although Italian government debt benefits from the European Central Bank’s pledge last year to “do whatever it takes“ to prevent a euro-zone break-up, it wasn’t so long ago that the yields on Italian bonds were nearly twice their current level. Another bout of market turbulence would reactivate this “doom loop“ between banks and the government.

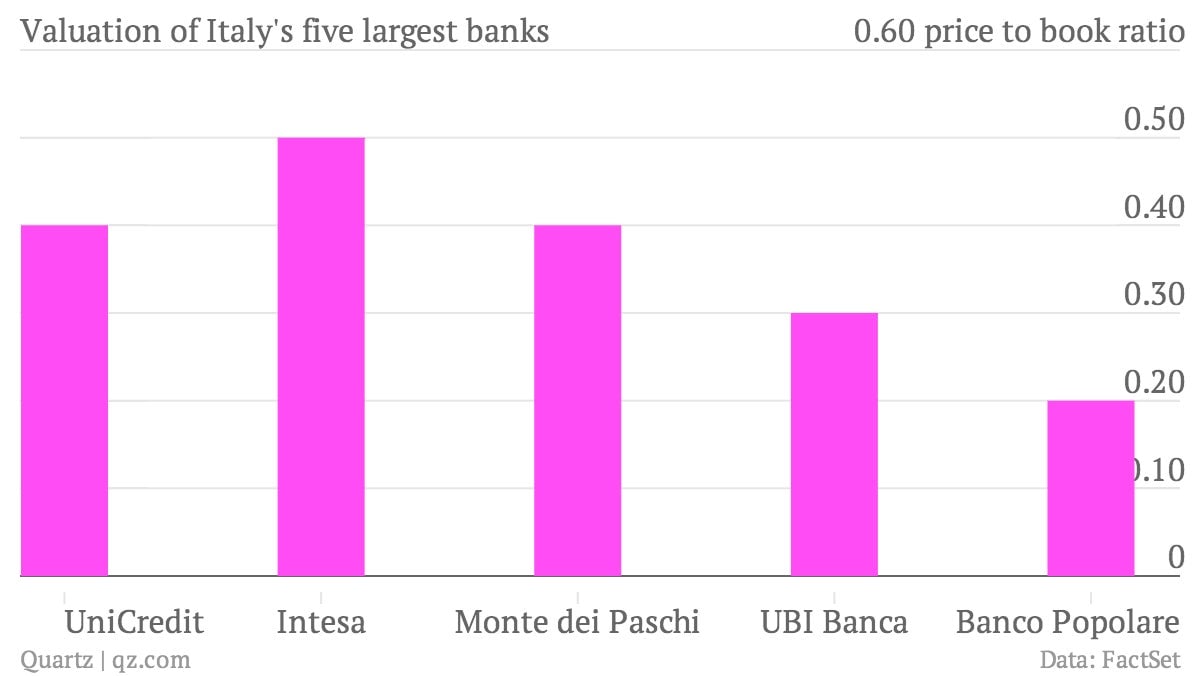

Although Monte dei Paschi is possibly Italy’s sickest bank, the others are hardly pictures of health. According to price-to-book ratios, investors believe that the assets of Italy’s largest banks are worth no more than half of what banks report in their accounts. With bad debts growing by more than 20% a year thanks to two years of recession, it’s not hard to see why.

And so Monte dei Paschi’s attempt to raise extra capital, when it comes, will be a pivotal moment for all Italian banks. These banks have weathered the euro crisis so far, just, but there is little room for error. If one bank falls, it might set off a chain reaction.