With these patents, Apple could win the next major platform war

The next stage of the platform wars may be in health.

The next stage of the platform wars may be in health.

Despite being one of the most regulated sectors, where change is driven as much by law as by technological advances, the big tech giants are active. Amazon, JPMorgan, and Berkshire Hathaway are teaming up to form an independent healthcare company for their employees in the United States. Alphabet’s Verily is moving into health insurance. And to consolidate, traditional healthcare giant Cigna has announced (paywall) it is buying pharmacy benefits firm Express Scripts.

While the same rules for platform domination will likely apply—adoption that builds on network effects aided by the power of Big Data and increasingly sophisticated AI—only one company already has a popular health-tracking device on sale that is essentially a supercomputer that’s always on your body.

The Apple Watch continues to grow its sales, which it doesn’t disclose but are already presumed to be in the tens of millions annually; one report suggests that Apple sold more watches last quarter than Rolex, Omega, and Swatch combined.

And the pipeline suggests that Apple has even more plans for its smartwatch.

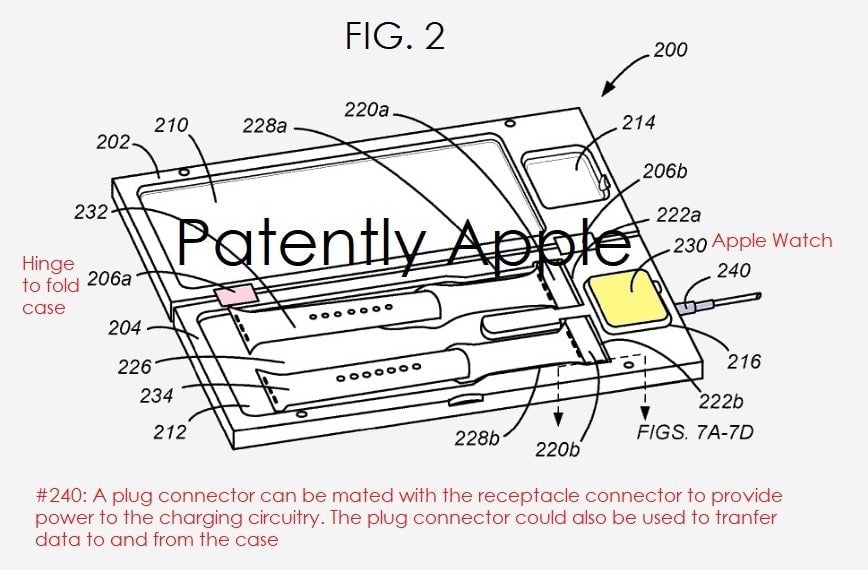

At the end of February, Apple was awarded a patent for an Airpod-style charging case that can hold a watch but also a number of bands. This isn’t just a fashion accessory; the bands in question are “smart bands,” electronic devices in their own right. The reason you’d want more than one band might be because Apple might think that the next generation of medical devices will be for conditions that need more than one physiological measure—such as blood pressure and blood glucose for managing diabetes or glucose intolerance—and that measuring these body signals will not be possible in a single wearable.

(These bands aren’t fantasy—a company called AliveCor already offers the first US FDA-approved electrocardiogram reader for Apple Watch called Kardiaband, which may also be able to detect high potassium levels in the blood.)

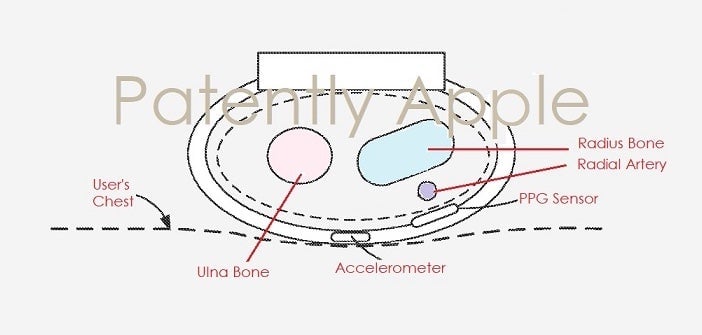

Last year, Apple was also awarded a patent for a very clever way of measuring blood pressure with a Watch, where you can hold the Watch against your chest and a controller is configured to process output signals from an accelerometer. It detects when your blood-pressure pulse is propagated from the left ventricle of your heart, detects when it arrives at your wrist, then calculates a pulse-transit time that is then used to calculate your blood pressure. The accelerometer is dead in the middle of the band, not in the body of the Watch. This makes us think that there’s not much else that can go in that band, except perhaps a battery and maybe some colored lights.

Another area to speculate on is what else Apple may be thinking of monitoring. In the US alone, there are 115 million people who suffer from some form of pre-diabetes, diabetes, or hypertension. Many people actively monitor their diabetes through physiological monitoring of blood glucose with a finger prick test. Blood-glucose measurement through non-invasive means is a significant challenge and no one has figured out a reliable way to do it accurately.

But rumor has it that Apple is on the case. This is a very tough technical challenge that people have been trying to solve for decades. We suspect that Apple’s case patent may be an indicator that it will not be possible or desirable to use one band for both blood pressure and blood glucose, or anything else for that matter, for at least the next decade. So you might not be monitoring everything all of the time but you may be easily able to switch out charged smart bands that are fashionable and conceal that you are being monitored.

Apple needs the Watch to win the health-platform wars. They know you’ll want to preserve your privacy by being able to disguise what you are monitoring. They know you’ll want to be able to effortlessly store and connect because you will be required to supply all the data to your doctor, insurer or employer. They know that anything less will feel like the monitoring—and hence the condition—has taken over your life.

We think that only Apple can make medical surveillance bearable, much less cool. Which makes an Apple Watch, smart bands, and a case that does it all, an essential purchase. At that point, the Watch system is a lot more than just a $400 watch and the market isn’t just consumers—it’s employers and insurers who figure out the new economics of health as a platform service. The overall market for watches is likely smaller than phones but Apple’s competitive advantages in design, technology, and data security could give it a significantly higher market share in watches.

This is especially true for insurance company buyers who will be focused on effectiveness and security much more than price. If Apple emerges as the safe purchase for corporate buyers, the Watch could be the next big thing that investors have been looking for since the iPhone.