We talked to slime mold about philosophy (through a human interpreter)

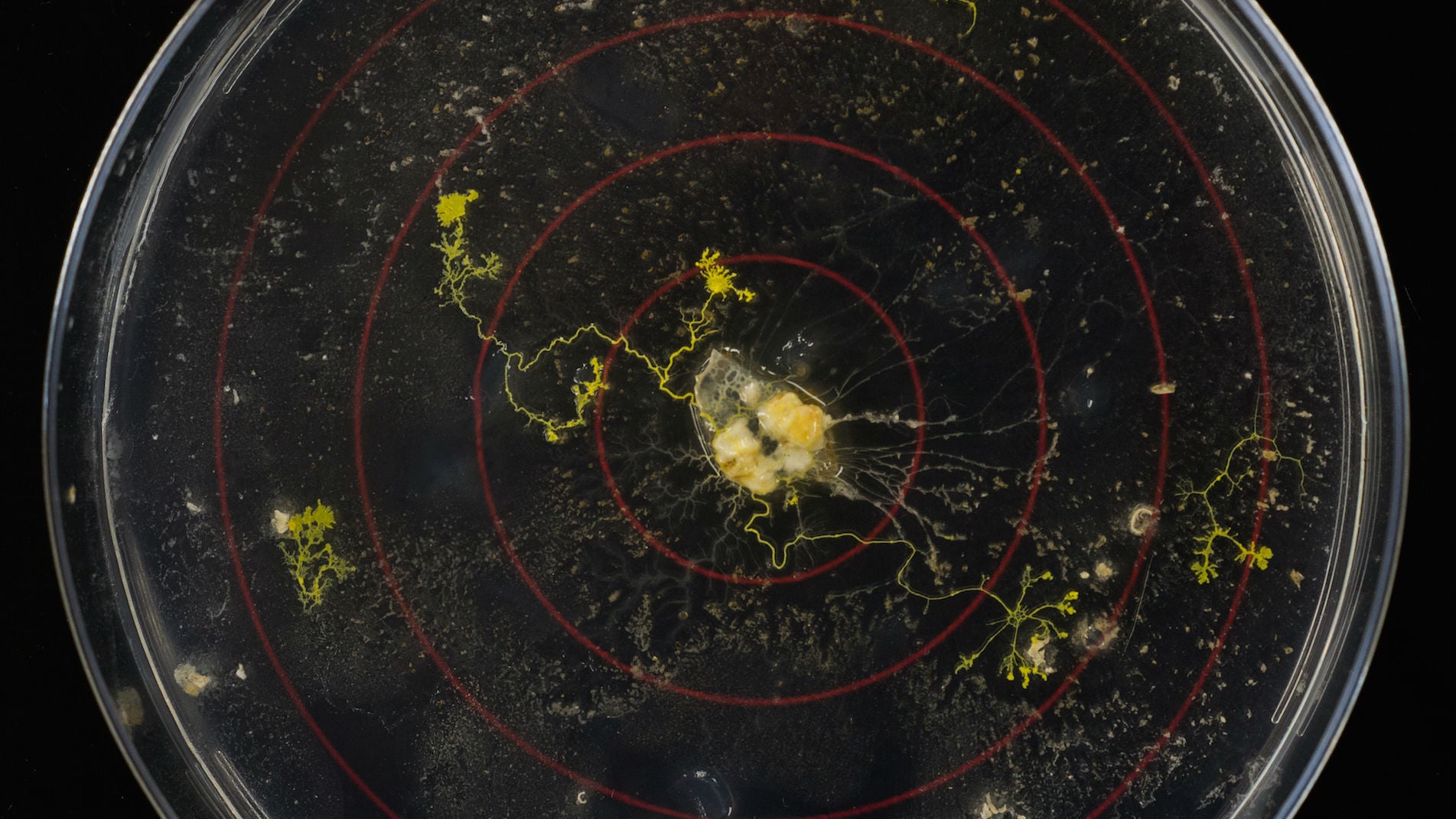

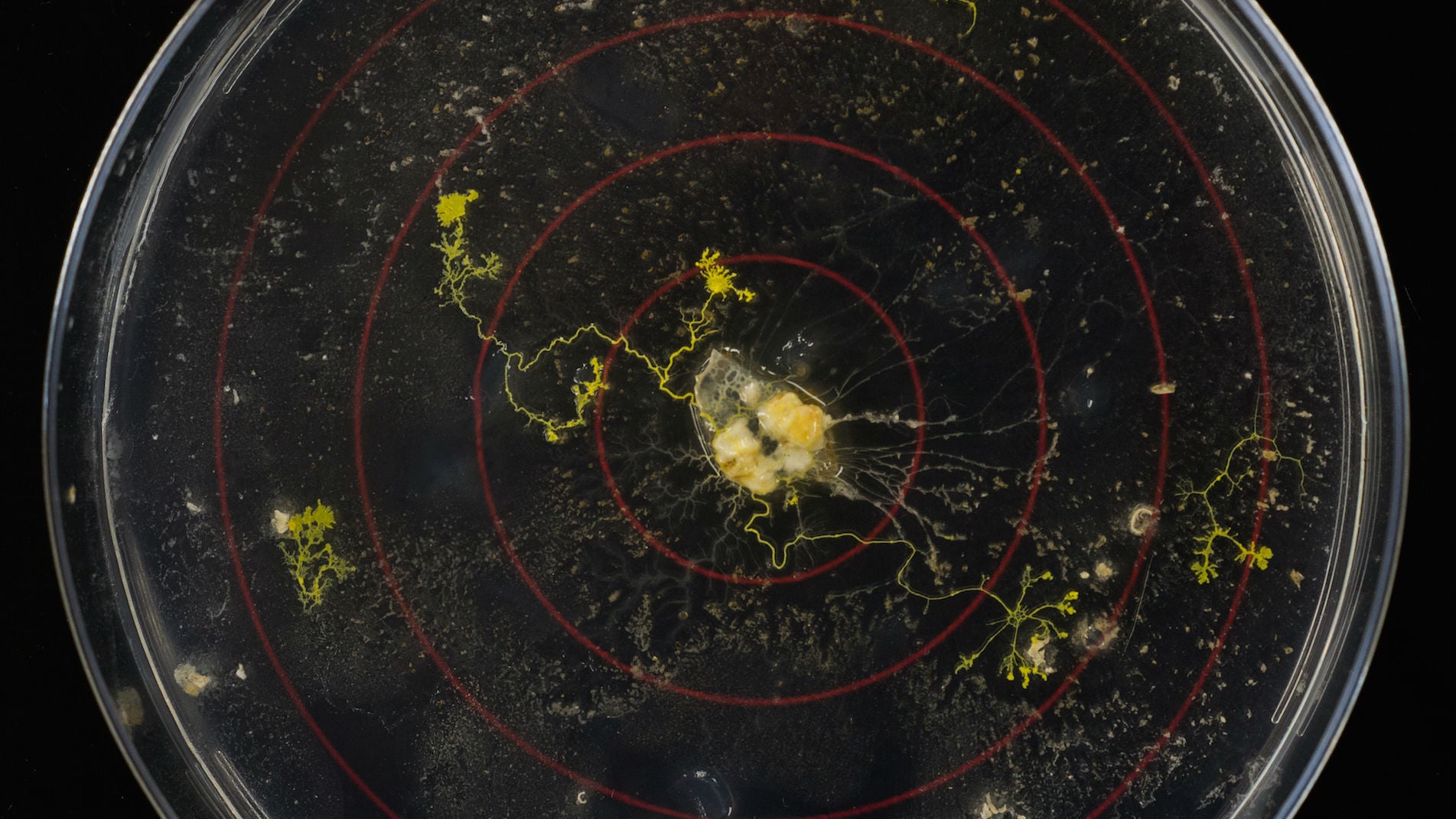

Each Physarum polycephalum is a single, gelatinous amoeba made up of thousands of nuclei, all floating together in cytoplasm. You can think of these slime molds, commonly found in temperate forests, as an amorphous, moving cellular jello. All of a given slime molds’ nuclei are both completely independent and function as a part of a whole. Which is why, even though the slime mold currently serving as Massachusetts’ Hampshire College’s visiting nonhuman scholar is one being, in interviews, they refer to themselves using the pronouns we/they/their.

Each Physarum polycephalum is a single, gelatinous amoeba made up of thousands of nuclei, all floating together in cytoplasm. You can think of these slime molds, commonly found in temperate forests, as an amorphous, moving cellular jello. All of a given slime molds’ nuclei are both completely independent and function as a part of a whole. Which is why, even though the slime mold currently serving as Massachusetts’ Hampshire College’s visiting nonhuman scholar is one being, in interviews, they refer to themselves using the pronouns we/they/their.

It may seem like a stretch to call a slime mold a “scholar,” but the biologists and philosophers working with Physarum at the college disagree. The Hampshire team believes we can solve some of humanity’s biggest problems by modeling Physarum’s behavior. “Slime molds are not Republicans and they are not Democrats; they’re neutral; they’re other,” independent experimental philosopher Jonathan Keats told Vox. In lab settings, the mold has been able to recreate maps of efficient subway routes (paywall), which inspired Keats to convince Hampshire to give Physarum a residency. The slime mold, he believes, can show us what policies would actually be the best for the biggest groups of people, without any external influences.

Despite not having limbs (or a brain), Physarum has plurality, which what may give them a leg up on humanity. Although a slime mold amoeba can exist with a single nucleus, when they run into each other they join forces, and begin to function as a unit. Individual needs are set aside for what benefits the amoeba as a whole.

As Physarum grows, they branch themselves out in search of food, and away from light. When one branch of the amoeba encounters their preferred meal of dead plants, the rest form a beeline (slime-line?) toward it; in the case of light, the growth shirks away. Scientists still don’t know how the mold communicates within themselves. But Keats, along with Hampshire College colleagues Megan Dobro, a biologist, and Amy Halliday, an art curator, are now assisting students in using Physarum to model various socioeconomic problems with their growth patterns.

The mold cannot talk or type, so Dobro served as a human interpreter while Quartz’s interview with them. “They shy away from having opinions about anything,” says Dobro, “which is why we like them so much. However, I sat with them for many hours on these questions and felt I understood the answers.” The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Quartz: What has been the most important thing you’ve taught students through experiments with you so far?

Physarum: We hope the students have come to understand that the only way to survive this changing planet is to work together, as a human race and in collaboration with all other life on Earth. Individuals only thrive when the whole community thrives. No one of us is as important as all of us. With that mindset, maybe they too can live on this planet for nearly a billion years (paywall).

Together we’ve worked on problems of border policy, drug addiction, food deserts, materialism, and the local bus system budget cuts. We have found that we thrive best in an open border situation, that access to healthier options could reduce drug addiction, that grocery stores should be spaced more evenly to allow better access for all, that environments with low toxicity are favorable to affluence, and that slime mold can help humans to map efficient public transportation systems.

What is the driving principle that helps you make decisions?

Ultimately, we’re just in search of the most ideal conditions, and we find them by joining our efforts and sharing what we find. Humans have so much food and wealth but they don’t distribute the resources well. We like lots of food and an environment that is warm, dark, and moist, but when we are putting in too much effort with little reward, we package our genetic information into hearty spores and wait as long as it takes until the conditions become favorable again. Maybe it will take a thousand years, but it means our species will survive and our grandchildren will have an easier life. Some of us even give our lives to make sure this happens. Humans would do well to think more about their future generations rather than destroying the planet for a more comfortable life now.

How do you think humans can apply these values to our politics and policies as a whole, and for smaller, interpersonal relationships?

For smaller, interpersonal relationships, we have found constant communication and sharing everything to be the healthiest way. Also, we make all decisions by committee and then everyone commits to those decisions together.

What do you think humans’ biggest shortcomings are, and how should we overcome them?

Humans think too much about their individual wants rather than the needs of everyone. As we said above, we’ve found success through combining efforts and sharing everything.

What do you think humans’ greatest strengths are, and how can we maximize them?

Humans are innovators and inventors. That will take them far if they maximize their workforce. Too many talented humans are being left out because of cultural habits.

Is there anything that has surprised you about humans since you started working with them at Hampshire?

One really surprising trait of humans that we’ve learned is that they find answers to their problems but then don’t act on them. We’ve helped to write letters to people designated to enact the changes, but we’ve received no reply so far. For many of the problems, the humans already knew the answer. We merely confirmed what they already knew. And yet, the problem persists. How strange.

What are your plans after your tenure here?

As long as the humans keep giving us oatmeal we plan to stay! (Editor’s note: oatmeal is Physarum’s favorite food.) If they stop feeding us, we’ll just move along until we find more food. Luckily, Hampshire College is surrounded by forest, so we’ll happily live there.

What is something you know now you didn’t know last year?

We now know the science building has a lot of oatmeal. We hope to learn where there’s even more oatmeal! We’re good at learning how to get to food as quickly as possible, so we’ve become even better at finding the oats and will continue to teach our children the same skills.

Are there any books, movies, or other forms of media that have influenced your worldview?

Well, it’s more that the humans have shown us books that confirm what we already knew. For example, Emergent Strategy by Adrienne Maree Brown provides a great explanation for how we live and make decisions. We’re also really proud of the movie, The Creeping Garden, which we helped to make.

What do you do for fun?

We eat! And make more of us. We spend a lot of time trying to find our way in the dark.

Correction: A previous version of this article implied that Jonathan Keats was a faculty member at Hampshire College. It has been updated to reflect that he is an independent experimental philosopher working with Hampshire for this specific project.