Russia’s election is so predictable we already know many of the numbers

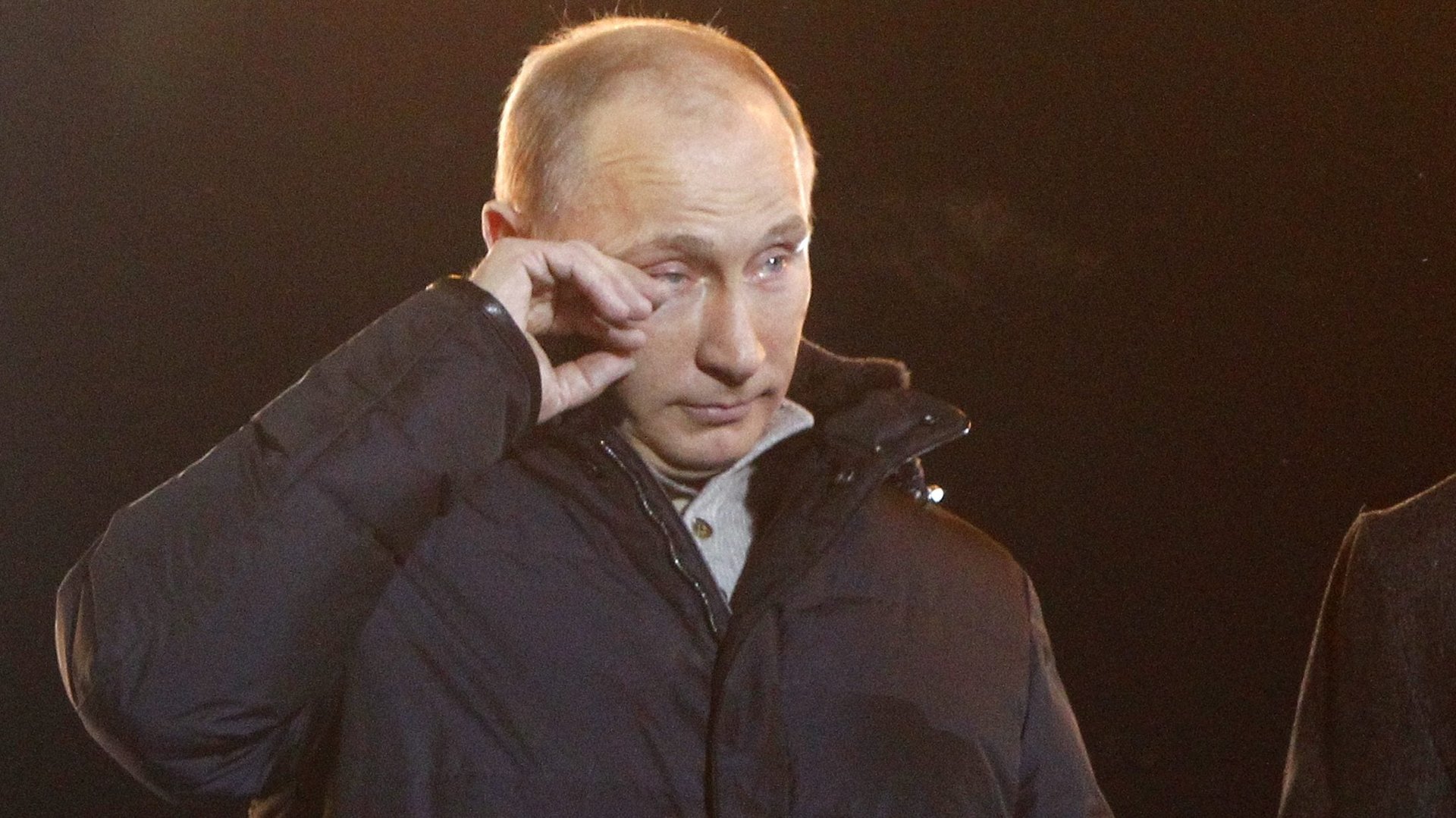

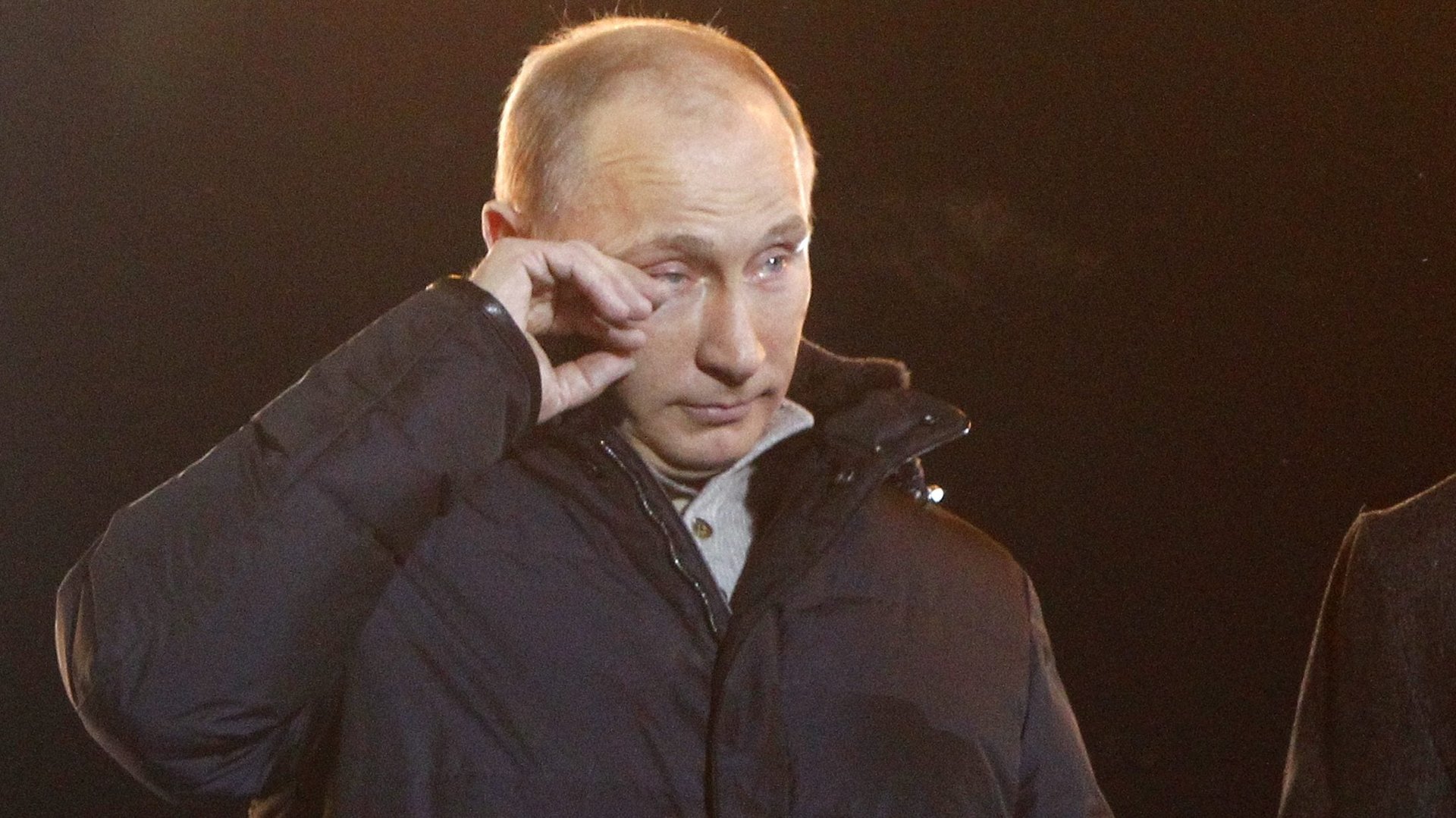

No one is holding their breath for the Russian election. Everyone knows that president Vladimir Putin will roll straight back into office and remain there until 2024.

No one is holding their breath for the Russian election. Everyone knows that president Vladimir Putin will roll straight back into office and remain there until 2024.

His incredibly high poll numbers—conducted by state-run pollsters—mean the only real question is what the final tally will be.

But even that figure isn’t in too much doubt. Putin’s team has set out a goal of 70:70. That’s 70% turnout, with 70% of the votes going to the president. Russia experts gave Putin a very good chance of hitting the figure for his personal votes. While Russian elections are always marred by accusations of fraud, Putin’s genuine popularity and the lack of credible alternative mean he would likely get 60% to 65% even without any shenanigans on the day, says Nina Khrushcheva, professor of international affairs at the New School. “They’ll fudge the rest,” she wrote in an email to Quartz from Moscow, predicting around 10% would be added fraudulently.

You can also make a very educated guess at the results he’ll get in some regions. The republics of the North Caucasus traditionally put out eyebrow-raising numbers, with turnout and votes for Putin in the high 90s. On Sunday, “120% is possible in Chechnya and Dagestan,” says Andrei Piontkovsky, a visiting fellow at the Hudson Institute and fierce Kremlin critic. It’s not that comic of an exaggeration—in 2012, one precinct in Chechnya reported a 107% turnout. Local elites in those semi-lawless regions use their preposterous numbers to send a message of respect to Putin, Piontkovsky says, so anything lower than the high 90s would be a sign of significant dissent. “Maybe one interesting result will be in Dagestan, where Putin and his power structure are arresting a lot of local leaders on the context of cracking down on corruption,” he said.

While these numbers help the overall turnout, the 70% figure will be hard to reach, says Oksana Antonenko, a visiting professor at the London School of Economics. Leading opposition figure Alexey Navalny has called for a boycott of the vote after he was barred from running, but the machine is finding subtle ways to manipulate the number, Antonenko says. “The focus is on the turnout, with employers threatening to fire people who do not vote,” she wrote in an email. “I think 70% is very unlikely, the key question is how far above 60% it is going to be. The benchmark could be the 2012 elections, when turnout was around 65%, so anything above that could be claimed as a victory by the Kremlin. Below that will be problematic.”