When Trump calls for the death penalty to drug dealers, does he mean Big Pharma?

Donald Trump announced a new US policy in New Hampshire yesterday—the US would seek the most severe punishment for drug dealers to combat the country’s crippling opioid epidemic, he said, a move quickly affirmed by the Department of Justice. “If we don’t get tough on the drug dealers, we’re wasting our time,” the US president said, “and that toughness includes the death penalty.”

Donald Trump announced a new US policy in New Hampshire yesterday—the US would seek the most severe punishment for drug dealers to combat the country’s crippling opioid epidemic, he said, a move quickly affirmed by the Department of Justice. “If we don’t get tough on the drug dealers, we’re wasting our time,” the US president said, “and that toughness includes the death penalty.”

But in the case of prescription opioids, who counts as the dealer? Should careless doctors be held responsible? Drug manufacturers? Marketing executives? Big pharma investors? Drug store chain owners?

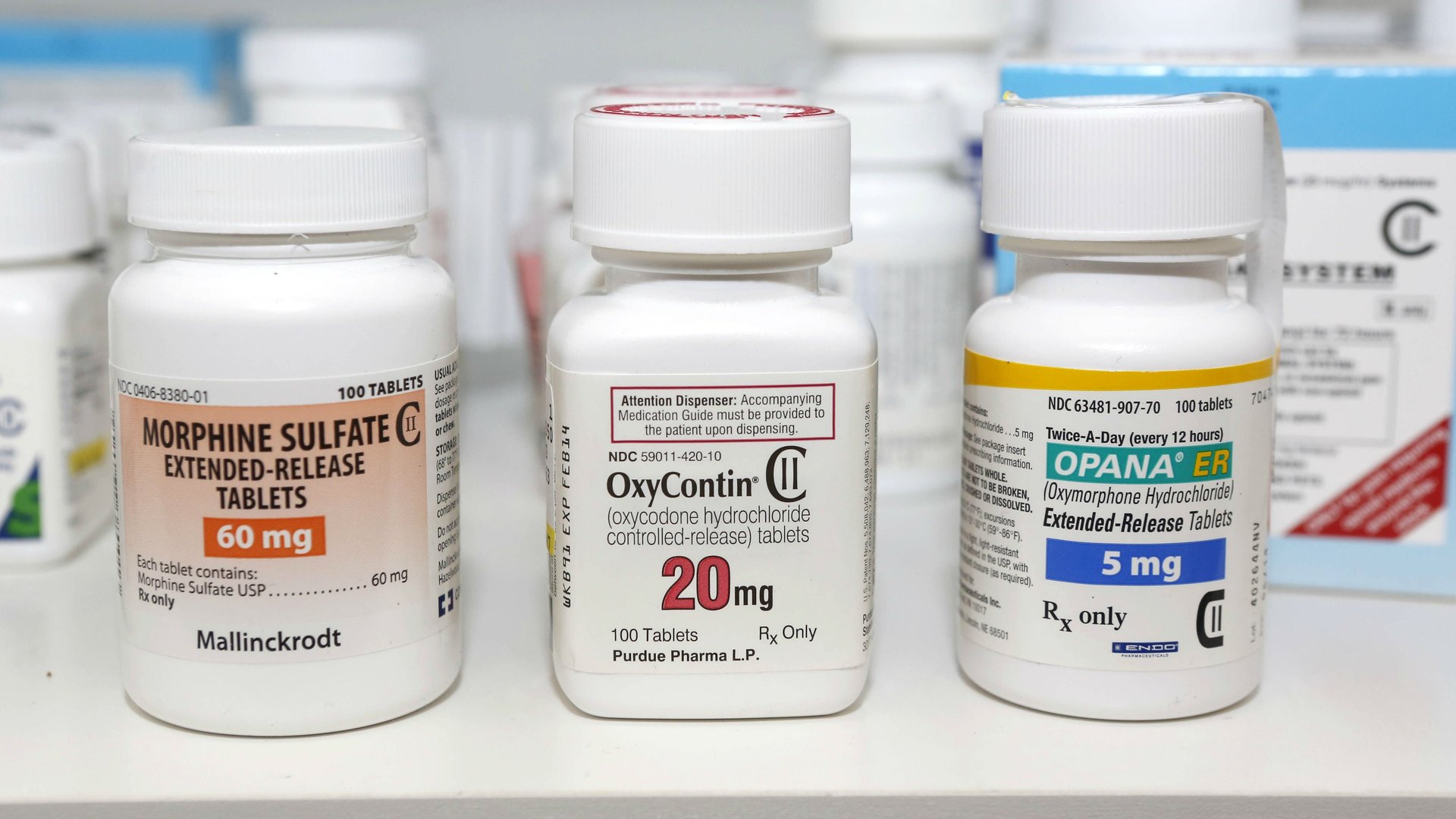

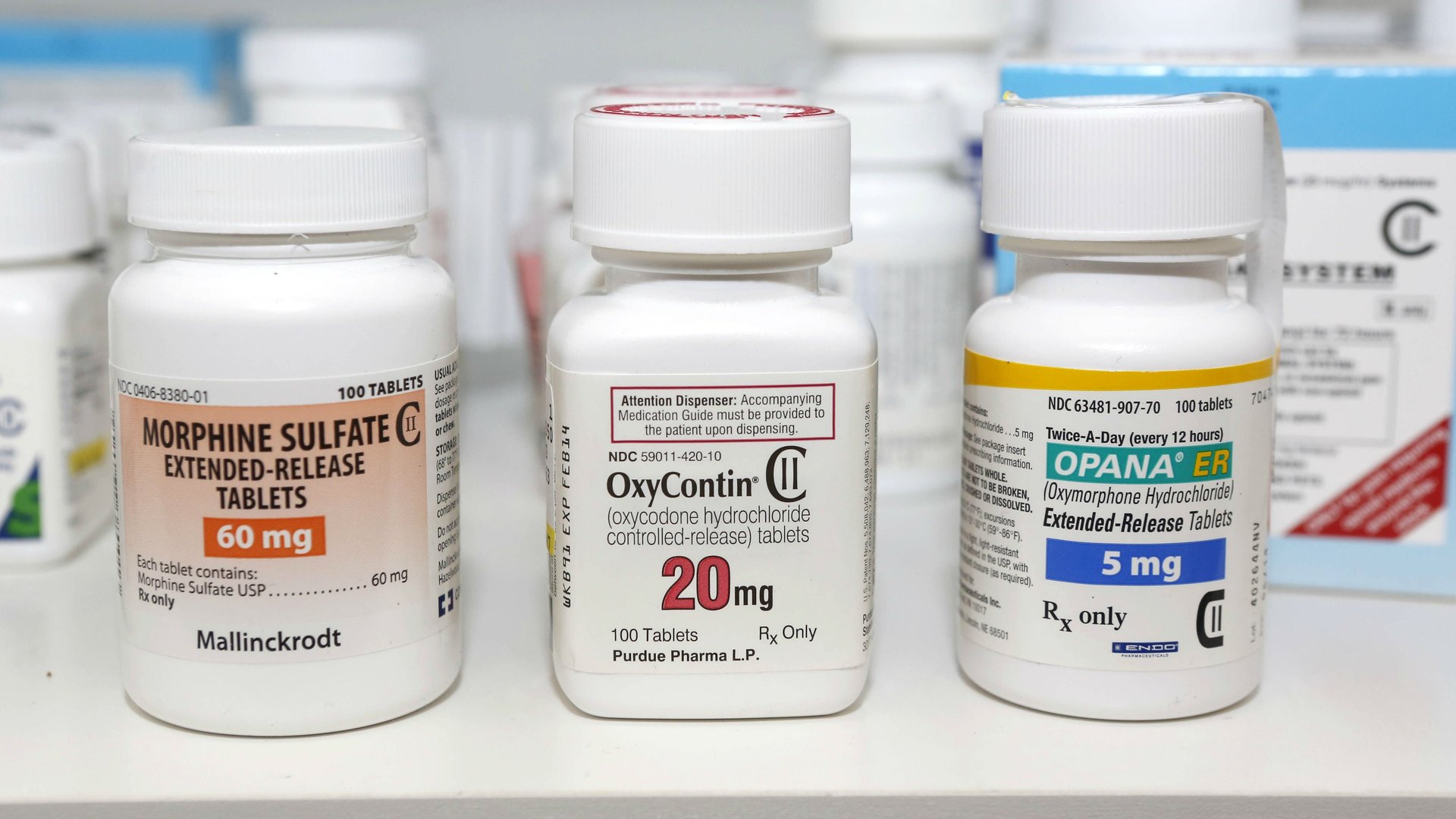

The US opioid epidemic has its roots not in the streets, but in a legal pharmaceutical industry that rakes in $450 billion annually in sales. A growing body of evidence finds the epidemic started and grew because of the over-availability of legal prescription drugs: State and local governments have brought hundreds of lawsuits against drug manufacturers and big drug store chains in recent years, alleging that drug companies knowingly mis-marketed these substances while lobbying politicians for regulatory changes that artificially inflated the market, and that drug stores broke federal law by failing to report huge unusually large orders of drugs.

Today, Americans consume far more prescription opioids than anyone else in the world.

Most overdose deaths in the US are from prescription drugs. These drugs also serve as a gateway to heroin, an illegal opioid that can be cheaper and easier to get on the black market than prescription medication.

Purdue, the manufacturer of OxyContin, is the target of a criminal investigation in Connecticut over the way that it marketed the drug, and particularly whether the company ignored evidence that the drug didn’t last for 12 hours as it promised. It agreed in 2007 to pay nearly $650 million for ”unleash[ing] a highly abusable, addictive, and potentially dangerous drug on an unsuspecting and unknowing public.” The record sum was part of a plea agreement that kept three top Purdue executives from being sent to jail.

Pharmacy chains CVS Health, and Walgreens Boots Alliance are also being sued by the Delaware attorney general for “shipping quantities of opioids around the country so enormous that they could not possibly all be for legitimate medical purposes,” and failing to take “basic steps to ensure that those drugs were going only to legitimate patients.” The suit, like others, alleges the companies’ actions created a huge legal market for the drugs, which in turn created an illegal market.

Meanwhile, pharmaceutical distributor McKesson agreed to pay $150 million civil penalty to settle a Department of Justice suit last January. Several executives from Insys, which makes a fentanyl spray, were charged with last October with bribing doctors to prescribe the addictive medicine. “The allegations of selling a highly addictive opioid cancer pain drug to patients who did not have cancer, make them no better than street-level drug dealer,” said the FBI agent in charge of the Insys investigation.

“We must hold the industry and its leadership accountable—just as we would the cartels or a street-level drug dealer,” acting US attorney general William Weinreb said about Insys. Indeed, under Barack Obama, the Department of Justice pushed to hold individual company executives responsible for corporate crimes. But it’s not clear that the regulation-slashing Trump administration will pursue that tactic, despite Trump’s threats.

In December, Weinreb was replaced by a Trump appointee, who said he would be prioritizing immigration offenses in his first meeting with reporters. Trump’s initial nominee for “drug czar” withdrew after it turned out that he backed a law that actually hindered federal prosecutions for opioid abuse. The new nominee, James Carroll, is a former deputy chief of staff in the White House who was previously Ford Motor’s in house lawyer and has no previous experience in the area.

Trump used his speech Monday to call yet-again for building a border wall with Mexico, and blame immigrants and sanctuary cities for crimes and rising drug use, despite research from his own commission (pdf, pg. 19) that blames the US healthcare system instead. The Department of Justice was looking at “major litigation” against certain drug companies, Trump said Monday, but he made no mention of the executives who run these companies.