Despite Uber’s fatality, most carmakers are carrying on with self-driving tests

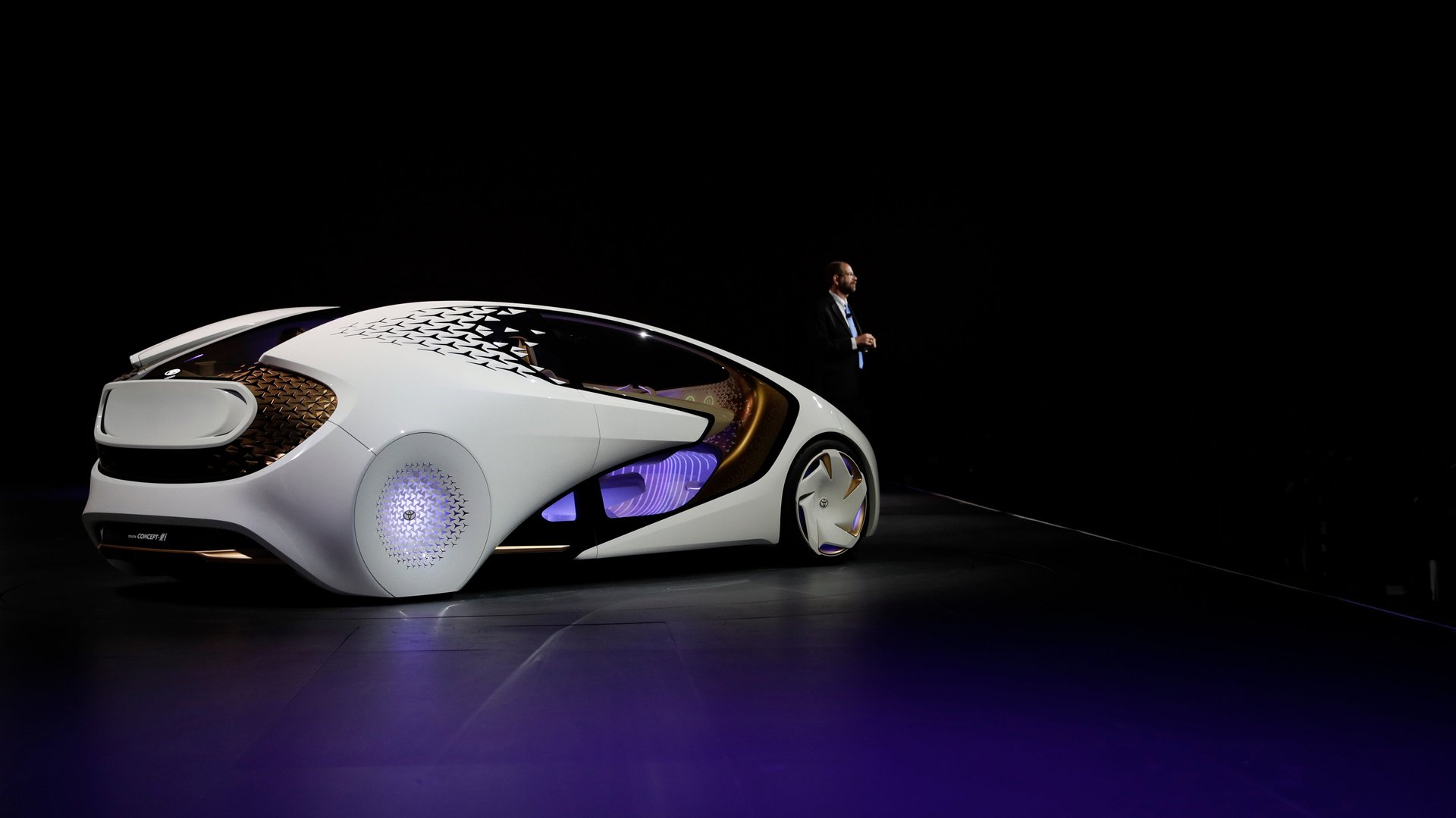

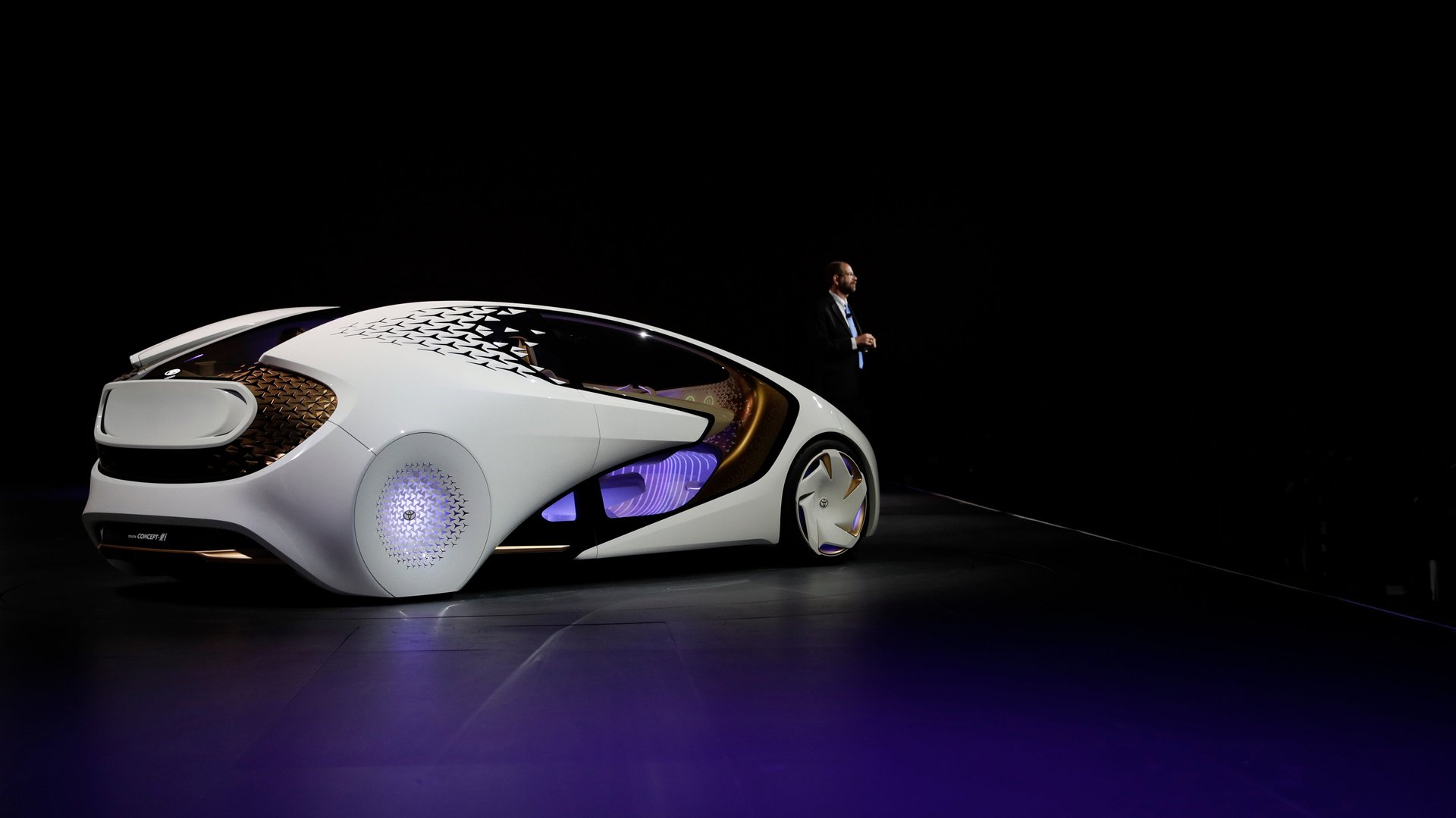

After an Uber self-driving car struck and killed a homeless woman in Tempe, Arizona on March 18, Toyota has announced that it will be temporarily suspending tests on its own self-driving car technology, which it calls Chauffeur, Bloomberg reported.

After an Uber self-driving car struck and killed a homeless woman in Tempe, Arizona on March 18, Toyota has announced that it will be temporarily suspending tests on its own self-driving car technology, which it calls Chauffeur, Bloomberg reported.

“Because we feel the incident may have an emotional effect on our test drivers, we have decided to temporarily pause our Chauffeur mode testing on public roads,” the Japanese car giant told Bloomberg today. (Uber has suspended all self-driving car tests, too.)

Toyota, like Uber and just about every other company that’s testing autonomous-car technology, employs a safety driver to sit in the front seat of the car to take over in the event that the car acts erratically or doesn’t respond to an issue. There was a driver in the Uber car that killed a woman, the company has confirmed.

Many automakers and Silicon Valley companies have set themselves lofty goals for getting autonomous vehicles on the road in the near future. General Motors’ Cruise Automation plans to launch a car without a steering wheel next year. GM declined to comment on any changes to its plans, although confirmed to Axios that it’s still pushing ahead for 2019.

Ford also confirmed to Quartz that it will continue with its autonomous testing. The new CEO, Jim Hackett, recently confirmed that he plans to stick to his predecessor’s plan of launching commercial autonomous vehicles in 2021.

Waymo, the Alphabet subsidiary, is already accepting regular people for rides in the Phoenix, Arizona metropolitan area (which includes Tempe). The Financial Times also reported today (paywall) that Apple has recently doubled the number of self-driving cars it’s testing, with it now second only to GM for the most autonomous cars on the roads in California. Representatives for Apple and Waymo weren’t immediately available.

But the commissioner of Boston’s transportation department, Gina Fiandaca, confirmed to Quartz over email that it has paused autonomous tests being conducted in the city by startups Optimus Ride and NuTonomy, an MIT spinoff that’s partnered with Lyft. ”The Boston Transportation Department will be working with both companies to review their safety procedures to ensure that each program can move forward,” she added.

‘We somehow need to accept that’

Toyota had been testing cars in California and Michigan, and had been in discussions to potentially team up with Uber—whose CEO Dara Khosrowshahi tweeted a photo from Uber’s lab with Toyota executives, including Gill Pratt, the head of the company’s research lab, just last week.

Quartz spoke with Pratt in 2016, soon after his joining Toyota and creating its $1 billion research institute. Here’s what he had to say about weighing the lives that autonomous vehicles will save against the ones it will invariably take as it improves, long before a robot car killed someone:

We have grown up, for whatever reason, as a society expecting machines to be flawless. So if a human being makes a mistake, and someone gets hurt, somehow we accept that. Around 30,000 people in the US lose their lives to cars each year. So you divide 30,000 by about 300 days in the year (plus or minus), and what do you come up with? 100 people every day. So if 100 people lost their lives in the US every day due to crime, due to terrorism, or accidents of any sort, the news would be going crazy. And yet 100 people every day lose their lives to cars and we somehow accept it.

We’re going to introduce technology which will drastically lower the number of deaths per year that occur. But some of the time, when that technology is in charge, an accident will still occur. When that happens, how will people view the occasional accidents that do occur? And unfortunately right now—or perhaps, fortunately—we have incredibly stringent expectations of performance and reliability for anything that’s mechanical. And so the hardest part of the work we have to do is to develop technology that will work at that level of expected reliability.

It may be that what we need to do is to get society to understand that even though the overall statistics are getting tremendously better, that there are still occasions when the machine is going to be to blame, and we somehow need to accept that. Because if we stop using the new software, we won’t get the benefit of this drastic average reduction.

This post has been updated with comments from Boston’s transportation department.