Entrepreneurship and Urban Growth: A Fresh Look Using Proximity to Mines

More than half a century ago, a classic article by the economist Benjamin Chinitz in the American Economic Review, “Contrasts in Agglomeration: New York and Pittsburgh,” sought to answer a vexing question about the mechanisms of regional economic development. He pointed out a connection between a region’s industrial structure and its ability to generate entrepreneurship, innovation, and new growth.

More than half a century ago, a classic article by the economist Benjamin Chinitz in the American Economic Review, “Contrasts in Agglomeration: New York and Pittsburgh,” sought to answer a vexing question about the mechanisms of regional economic development. He pointed out a connection between a region’s industrial structure and its ability to generate entrepreneurship, innovation, and new growth.

“For a given size of area,” Chinitz wrote, “the entrepreneurial supply curve is also a function of certain traditions and elements of the social structure which are heavily influenced by the character of the area’s historic specializations.” And he continued: “The proposition I offer is this: An industry which is competitively organized—in the neoclassical sense of the term ‘competition’—has more entrepreneurs per dollar of output than an industry which is organized along oligopolistic lines.”

Chinitz made his argument by contrasting the economic experiences of New York and Pittsburgh. New York’s diverse industrial and economic structures create its capacity for economic renewal and regeneration, and also gave it the ability to generate new rounds of entrepreneurial growth. Pittsburgh, in contrast, came to be a one-industry town dominated by steel and natural resource industries, which damped-down entrepreneurial spirits over time.

Shortly after Chinitz’s death in 2009, Harvard economist Edward Glaeser published a memorable tribute to him in the New York Times’ Economix blog. Glaeser wrote, ”In the almost 50 years since Mr. Chinitz wrote his paper, his insights have been regularly affirmed. Pittsburgh has continued to decline; New York has survived. Few now doubt that entrepreneurship is an important ingredient in local success.”

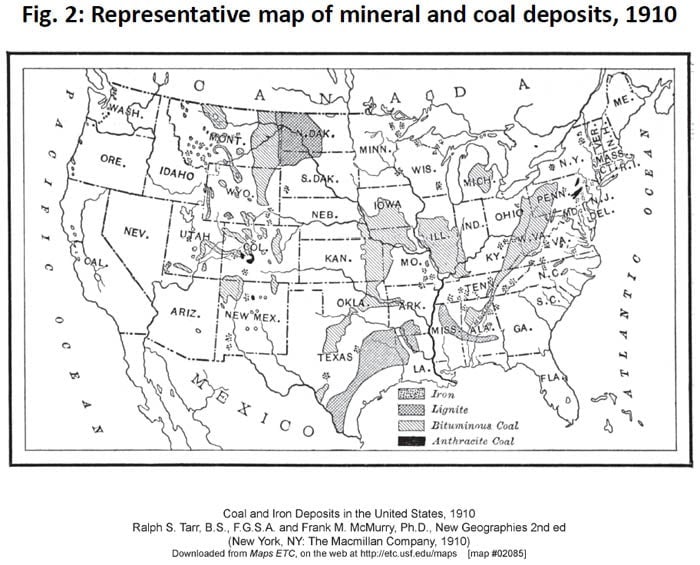

In his recent paper, “Entrepreneurship and Urban Growth: An Empirical Assessment with Historical Mines,” Glaeser and co-authors Sari Kerr and William Kerr subject Chinitz’s hypothesis to an empirical test, using proximity to mines (specifically mineral and coal mines) as a key variable. They argue that “proximity to historical mining deposits is associated with bigger firms and fewer start-ups in the middle of the 20th century.” The map below, from the study, shows the pattern of coal deposits in 1910, based on data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Their analysis finds that “[p]roximity to mines in 1900 predicts larger establishments, less entry, and less urban growth in trade, services, and finance today.” They note the “persistent link between entrepreneurship and city employment growth,” which works “primarily through lower employment growth of start-ups in cities that are closer to mines.”

They are careful to qualify their findings as follows:

The big concern with this variable is that it is quite plausibly correlated with aspects of the local economy other than entrepreneurship, such as manufacturing decline. We tried to control for these factors with city-level variables, region fixed effects, and so on, but we recognize that our measures are far from perfect. We focused then on industries that were not directly related to mining, and on industries that were highly concentrated spatially, which suggests that they do not depend on a local market. We also focused on warmer cities, which should be less sensitive to the decline of the Rust Belt, and we modeled city growth projections. Our core results remain unchanged. Finally, using quantile instrument variable techniques, we identified that our effects are present in both cities exceeding and underperforming growth expectations based upon their initial traits.

Based on this, they conclude that “[t]he weight of this evidence suggests that entrepreneurship is playing an important role in modern urban growth.” Their empirical analysis thus reinforces a key factor in regional development long ago noted by Chinitz and his contemporary Jane Jacobs — that economic and industrial diversity play a key role in the economic capacities of cities and regions.