The shape of your brain influences your political opinions

Most people turn to personal narratives or philosophical justifications to explain why they hold a particular political opinion. A recently published psychology study suggests they should also look to the size and shape of their brains.

Most people turn to personal narratives or philosophical justifications to explain why they hold a particular political opinion. A recently published psychology study suggests they should also look to the size and shape of their brains.

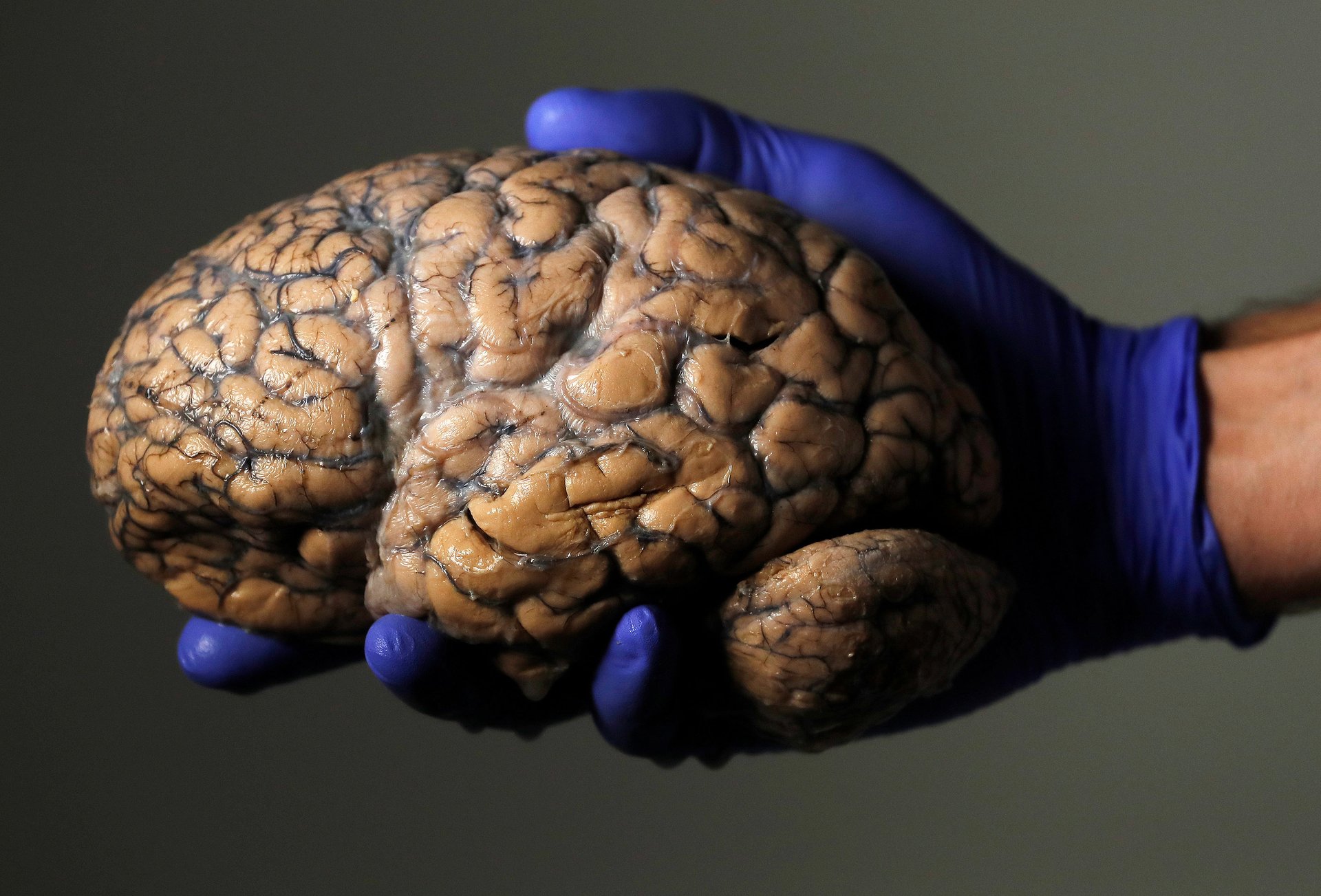

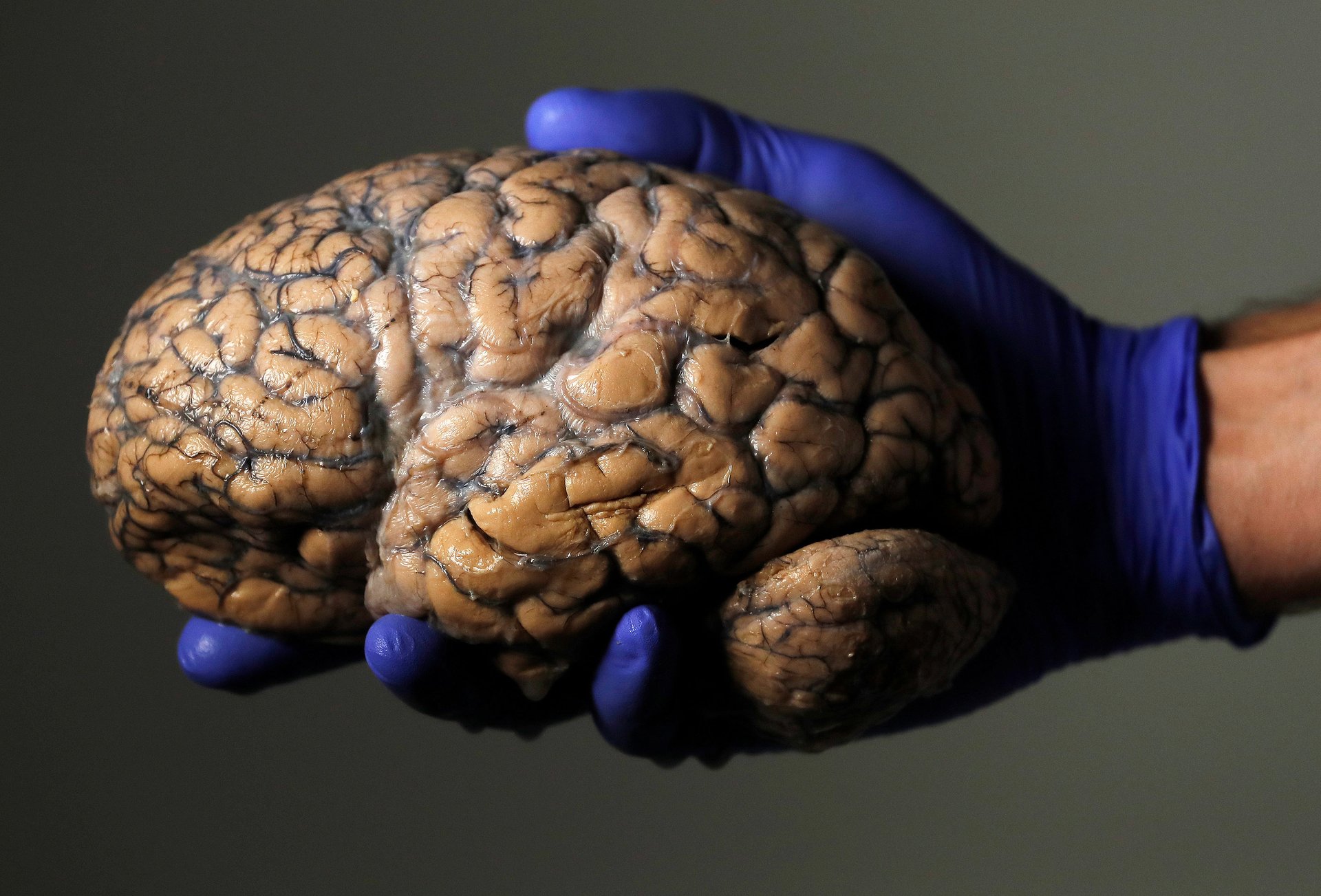

Psychologists conducted brain scans on a total of 93 adults (first they studied 48 Caucasian adults, 58% of whom were female, and then replicated the effects with 45 adults from diverse ethnic backgrounds, 67% of whom were female) and found that the size of the bilateral amygdala, which governs emotions, survival instincts, and memory, was strongly correlated with support for the existing social order.

This mindset is known as “system justification,” and is highly correlated with conservatism, says Jay Van Bavel, professor of psychology and neural science at New York University. “A system-justifying psychological orientation favours the social, economic, and political status quo, and may promote vigilance to social hierarchy and a preference for ideologies that characterize extant inequality as legitimate and necessary,” explain the authors in the paper, published in December in Nature Human Behavior. The study evaluated this by the system justification scale, which poses questions such as, “In general, you find society to be fair,” and “Everyone has a fair shot at wealth and happiness.”

Earlier research (notably one paper co-authored by the actor Colin Firth) found a link between conservatism and the volume of the right amygdala, with higher volume linked to conservatism. Van Bavel says his research found that system justification, more than specific political ideology or the tendency to legitimize economic inequality under capitalism, was the strongest indicator of variations in the size of the amygdala.

The authors followed up with 20 participants and found that those with larger amygdalas were less likely to take part in protests. “Although the sample size was small, this link between amygdala volume and protest behaviour provides initial evidence that the amygdala may not only be related to beliefs about society but also willingness to take action to change certain aspects of the social system,” note the authors.

These findings suggest that political beliefs aren’t only influenced by identity or party mandates, but by biology. “We think of politics as something driven by elites. When Donald Trump does something, the Republicans get in line and Democrats reverse their opinion,” says Van Bavel. “This is a bottom-up influence on politics. Whether or not we support ‘March for Life’ might just be whether we’re [biologically] predisposed.”

Brain structure, he says, is “part of the story” that explains what political parties and movements we find appealing. “It explains why it’s hard to make momentum and get everybody out protesting and to change things. A lot of people are dispositionally orientated towards the status quo,” he adds.

This research is in keeping with findings that genetics have a significant effect on influencing political preferences. “It seems quite likely that these biological predispositions are manifested in brain structure,” says Van Bavel.

The physical brain changes as our beliefs and behaviors shift (“virtually any change in behavior is mirrored by a change in brain structure,” says Van Bavel), and so it’s extremely likely that our brains change as our political views do over time. It’s difficult to know the extent that the brain we’re born with predetermines political opinions, as opposed to whether the brain is physically molded by the views we develop.

“If I had to place a bet, my money is on both outcomes: I suspect that our inborn brain structure guides us to political preferences, but that our political environment also alters our brain structure,” says Van Bavel.

Experiences and careful rational consideration can certainly shape the causes we choose to support. But, so too, can our physical brains.