The woman who made simple cooking widely popular 235 years before Martha Stewart

Long before Julia Child taught the world to embrace butter or Martha Stewart demonstrated how to make centerpieces out of pine cones, Hannah Glasse wrote a domestic guide for cooking and entertaining she hoped would ”improve the servants and save the ladies a great deal of trouble.”

Long before Julia Child taught the world to embrace butter or Martha Stewart demonstrated how to make centerpieces out of pine cones, Hannah Glasse wrote a domestic guide for cooking and entertaining she hoped would ”improve the servants and save the ladies a great deal of trouble.”

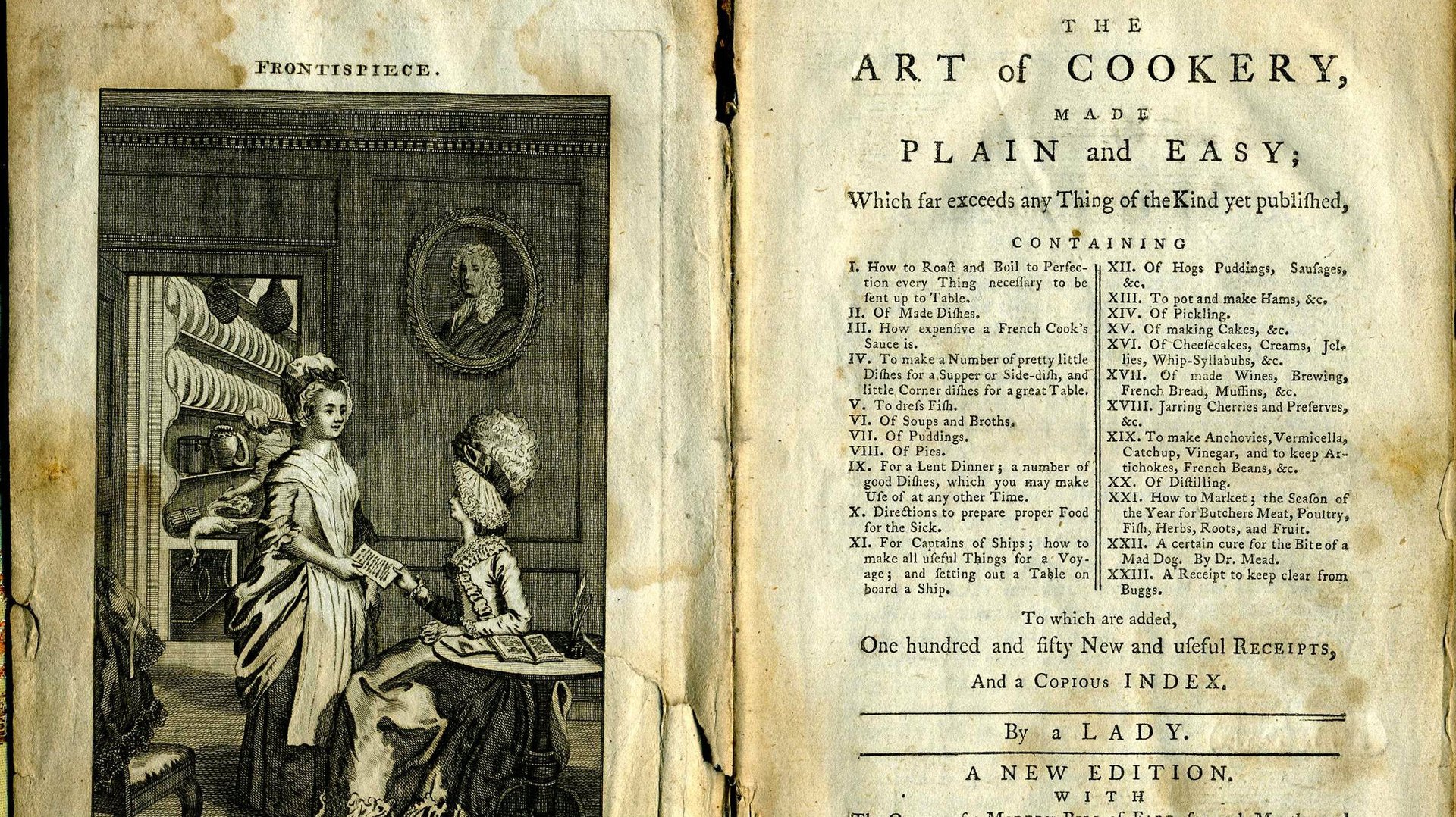

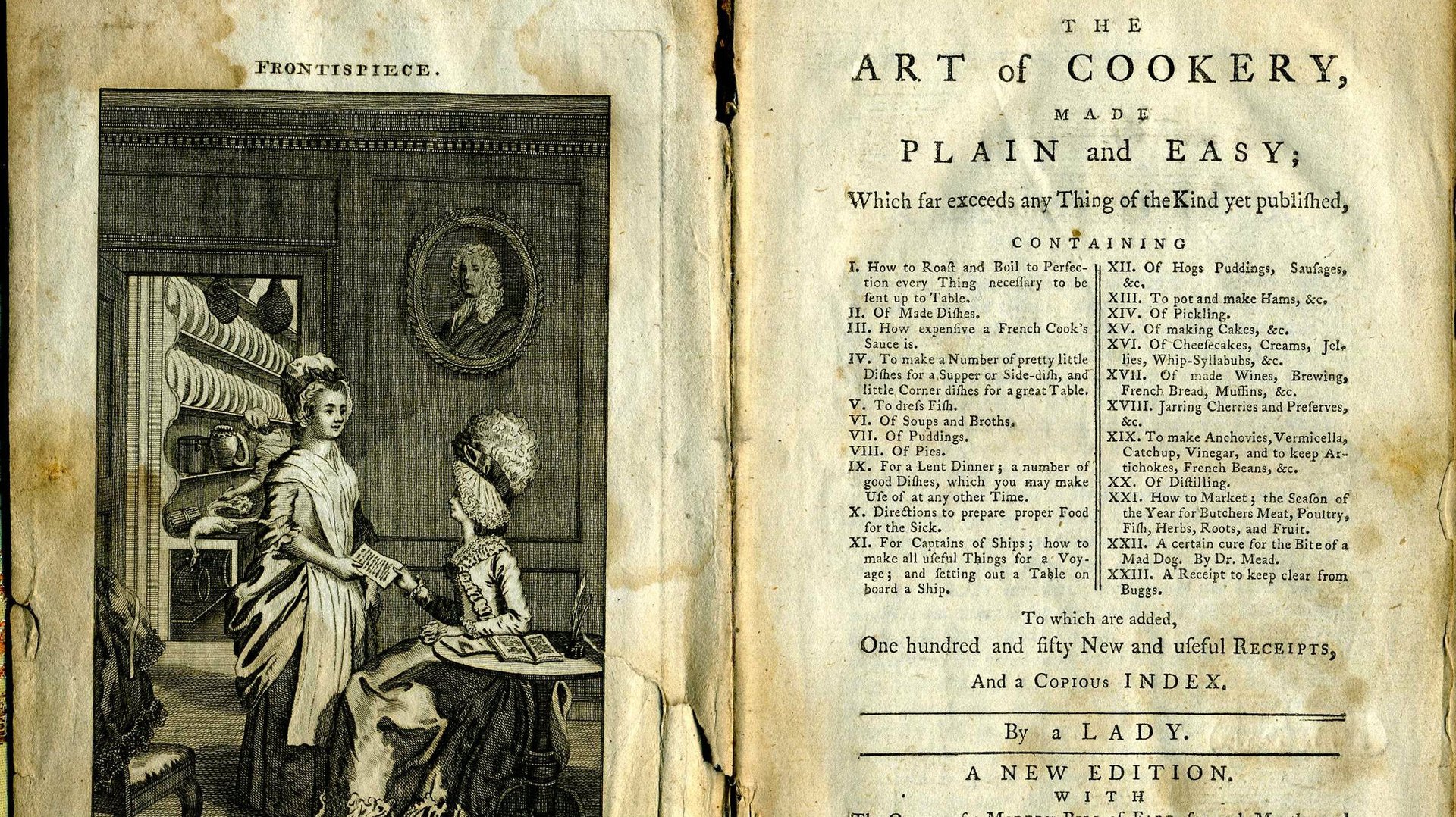

Glasse’s The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, first published anonymously in 1747—235 years before Stewart’s first book—became of Britain’s all-time popular cookbooks. It pioneered the concept of simple and accessible recipes and is thought to have remained a bestseller for more than 100 years after its publication (and is still in print today).

Today’s Google Doodle celebrates the 310th anniversary of Glasse’s birth.

The first modern cookbook

Glasse was among the first English authors to write down recipes, bind them into a book, and sell them directly to the public.

The Art of Cookery had a direct, conversational style, and stood in stark contrast to the elaborate recipe collections of its time, which were typically in French for professional chefs. In fact, there is an entire section in her book titled “Read this Chapter, and you will find how expensive a French Cook’s Sauce is.”

The book contained 972 recipes for everything from roasted hare to gooseberry fools (a traditional fruit and whipped cream dessert). It also has instructions on the “order and manner dishes are to be placed on the table.” Plus a chapter on long-lasting recipes “for the Captains of Ships.”

Glasse’s signature recipe was for Yorkshire pudding—a classic English dish made of batter served with roast beef and gravy traditionally offered for Sunday lunch.

Simple recipes, written in plain English

Glasses pioneered the concept of a conversational recipe book written in plain English so that any cook could make delicious meals at home.

Gourmet food had traditionally only been accessible to the wealthy, through the services of classically trained French chefs. Glasse’s book brought a new egality to the kitchen. “I dare say, that every servant who can but read will be capable of making a tolerable good cook, and those who have the least notion of Cookery cannot miss being very good ones,” she assured readers in the preface.

She scorned the “French tricks” popular in 18th-century professional kitchens and instead focused on traditional English fare. (She also included one of the first British recipes for Indian curry, a sign of changing tastes in the UK as the empire expanded its reach.)

Controversy and ruin

Though she may not have invented her hashes, jellies, and gravies, it was Glasse’s style that cemented her place in culinary history. Modern historians have accused Glasse of plagiarizing her recipes, after it emerged in 1983 that 263 recipes had been lifted almost word for word from The Whole Duty of a Woman, published in 1737. Plagiarism in cookbook writing was common practice at the time and the first Copyright Act of 1709 (The Statute of Anne) did not apply to cookbooks, so recipes were often copied from one author to another.

Though her book was incredibly popular, Glasse was forced to declare bankruptcy and to auction the copyright to The Art of Cookery (which revealed Glasse to be its author) in 1754. Apparently the auction was not enough—in 1757, she once again fell into financial difficulties and was said to have been consigned to a debtors prison for a few months.

Glasse authored two other books, The Servants Directory and The Compleat Confectioner, but neither achieved the commercial success of her magnum opus. In 1770, she died in London at 62.